College First-Year Stages Art Installation Prank

Keagan Tan’s fake art installation featured five crayon drawings with corresponding captions and a fictional artist biography accompanying a random internet portrait photo.

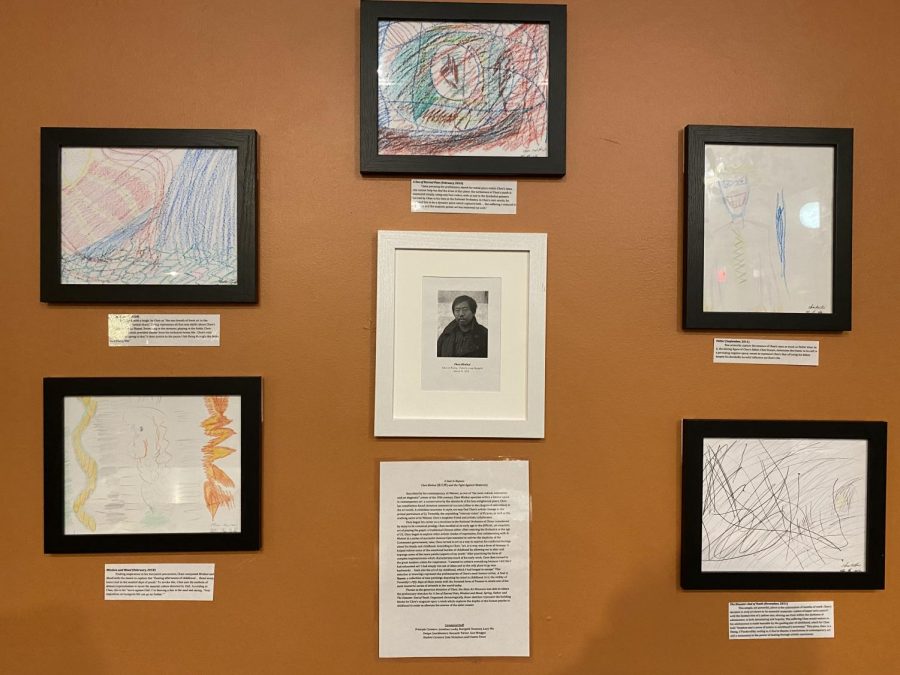

Several weeks ago in Wilder Hall, five framed drawings with individual captions were carefully arranged on the wall. The exhibition was titled A Soul in Repose: Chen Minhui and the Fight Against Modernity. The page-long description explained that Minhui, the artist, was a musical prodigy in the guqin, a Chinese stringed instrument, from a young age, but partnered with contemporary artist Ai Weiwei to “satirize the duplicity of the Communist government.” At the center was a black-and-white portrait of Chen, standing in Beijing in winter with a somewhat solemn expression.

The crayon drawings on the wall were confoundingly simple, rendered with the artistic literacy of a 5-year-old. Yet, the exhibition descriptions urged the viewer to consider the art as a representation of Chen’s childhood and the “building blocks for Chen’s magnum opus.” One piece, titled “Father,” depicted a man with stringy, green hair and a monstrous, red mouth; the caption elaborated, “To his left is a pervading negative space, meant to represent Chen’s fear of losing his father, despite his decidedly harmful influence on his life.”

In fact, the entire exhibition was a prank that took less than an hour to put together. While the description claimed that the Allen Memorial Art Museum obtained the pieces, the principal curators — Jonathan Lucky, Marigold Sweeney, Lucy Wu — were made-up names. The “portrait” of Chen Minhui was from a stock photo website, and the crayon drawings had no deeper meaning.

There was no 5-year-old mastermind behind the ruse, nor any enigmatic artist seeking to “explore the depths of the human psyche in childhood.” Chen Minhui is the Chinese name of Keagan Tan, a College first-year who has wasted no time making their mark at Oberlin.

Tan stressed that the installation was a simple prank, stating that they put “so little thought into this” but have greatly appreciated the amusement and attention it has gathered.

“It was literally pure impulse,” Tan explained. “It was just because I was just thinking of all the memes about modern artists. I saw a painting that was sold for like, $50,000, and it was just a white canvas. And I thought, ‘That would be funny if I did that at this school, which is known for very critically-thinking students.’ Even if students take STEM, they have taken enough classes in the arts and humanities where they have a good critical eye for this kind of thing. So I thought it would be funny if I preyed on that a little bit and just put up the installation.”

Indeed, some students did fall for it. Rising College second-year Ian Watson, a friend of Tan’s who had no idea Tan created the art, recalled his shock at how elaborate and professional Tan’s prank was.

“Being here, with the Allen, I’m pretty credulous,” Watson wrote in an email to the Review. “There’s art all over campus, so I just figured the stuff in Wilder [Hall] was some more. … I thought ‘Huh, that picture [“Father”] on the top right kinda looks like the Joker,’ which of course, it turned out to be, but I really bought into it that it wasn’t. When Ada [Ates] told me that the art was by Keagan, I was in denial. … It was really one of the most believable and funny pranks I’ve experienced in a long time.”

Watson added that the frames, lamination, and especially the captions were what made the prank extra convincing.

“It just had this sort of pretentious art language,” he wrote. “And I’m not an art major, so I guess I’m not great at discerning faux-art babble from the real thing. There were just so many small details that contributed to it, like the interpretations of the art on the labels, and the fact that the fake artist had all of these very intricate details, like that his relationship with his father was strained or that he joined the Chinese National Orchestra. It was all just brilliant.”

Tan explained that they managed to make the captions convincing enough by imitating the style and art terminology they had observed in real exhibitions. Their passion for film and art criticism allowed them to pump out the captions in forty-five minutes. The aforementioned piece “Father” addressed negative space simply because Tan noticed the white space in their crayon scribble and remembered the term, along with Ai Weiwei and the guqin, off the top of their head.

“I’ve been interested in film since I was four and consuming and reading art criticism and sometimes even writing cultural criticism on my own time for so long that I can bulls**t this thing just like that,” Tan said. “I guarantee that people who have seen the exhibit have put more thought into the exhibit than I have.”

The prank was so low-effort that Tan claimed they forgot all about it until they were contacted by the Review for an interview.

“I wasn’t expecting anyone to notice,” Tan added. “But, knowing Oberlin students, … there’s going to be some people who are going to try to analyze it, and that is the audience that will make for a good joke — if they actually believe this is real.”

However, talking about their piece for a student publication caused Tan to think about the various ways their prank could be interpreted — or misinterpreted. Tan suspected that some students were more likely to take the piece seriously because it featured a non-white “artist” set in a country they were less familiar with. They also considered whether the prank could be used to comment on cancel culture, particularly at Oberlin.

“I wasn’t even thinking about cancel culture [at the time],” Tan admitted. “The only time I thought about someone potentially getting canceled over this was when the Review reached out. Then I was like, ‘Huh, if I was white or if I was not Asian, this could be very uncomfortable for some people.’”

Joy Donnelly, another rising second-year student and friend of Tan’s, also commented that cancel culture did not cross their mind.

“I saw the art exhibit and bought into the premise, because I figured that the College wouldn’t have allowed someone to hang up the art in Wilder without permission, and, in addition, the art claimed to have been loaned to the Allen,” they said.

Perhaps the whole installation is just a classic case of “it’s not that deep.” But Tan does appreciate the retroactive commentary on cancel culture that their prank may have garnered.

“Identity can be fun,” Tan said. “If I have to retroactively give a point to the reactions and my interpretation of how I’m receiving it and processing it, it is poking fun at the discourse of cancel culture, but it’s not directly attacking anyone’s behavior and the way they reacted. It is totally reasonable for people to be afraid of being canceled. There’s not an ounce of anger or political pointedness with this thing. It was just a silly thing and if people want to laugh at it together, by all means. It doesn’t matter what their race is.”