Continued College Inaction Provokes Second Protest Against Mahallati

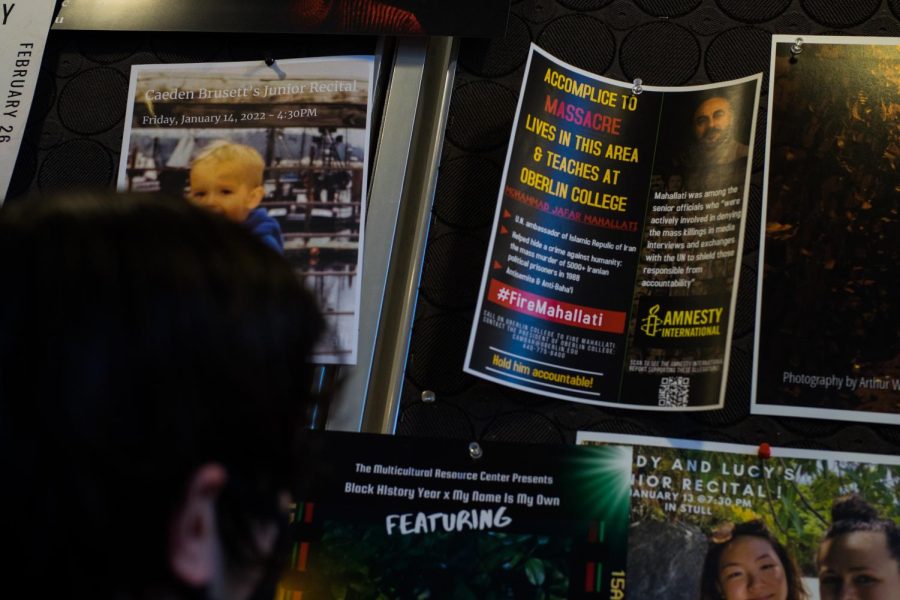

Activists have hung posters advertising the protest that will take place on Saturday.

Protesters are set to return to Oberlin this Saturday to demonstrate against the employment of Professor of Religion Mohammad Jafar Mahallati, who has been accused of covering up crimes against humanity in Iran in the 1980s. With minimal response from the College, the protesters are going to increasing lengths to gain an audience with the local community. While Mahallati has not responded to the Review’s request for comment, a source who has spoken to him recently shed light on an element of Mahallati’s past — namely that he was imprisoned and tortured by the Iranian regime in 1989, after advocating for the end of the Iran- Iraq War.

In October 2021, the College announced that it had conducted an investigation into Mahallati’s past, concluding that there was no evidence that he had “specific knowledge” of the executions taking place in Iran. In response to the College’s decision to stand by Mahallati, activists are taking to the streets of Oberlin for the second time. They are demanding that the College and its Board of Trustees transparently investigate the accusations — that Mahallati intentionally denied the occurrence of crimes against humanity in Iran — and ultimately, that they fire him.

“We, a group of families of executed political prisoners in Iran, Oberlin College students, alumni, and human rights activists, will protest for the second time at Oberlin to urge Oberlin’s Board of Trustees to order school officials to investigate the reported crimes against humanity conducted by the College tenured Professor Mohammad Jafar Mahallati and oust him,” read the press release from the Committee for Justice for Mahallati’s Victims.

In recent weeks, members of the committee have emailed individual members of the College’s Board of Trustees and sent flyers to Mahallati’s neighbors, accusing him of covering up crimes against humanity. The flyers can also be found in academic buildings and businesses across the campus and City of Oberlin.

According to Lawdan Bazargan, a vocal member of the committee, the College has yet to respond to any of its direct communications.

“President [Carmen Twillie] Ambar and the Oberlin administration has failed to transparently address the issues we outlined in our initial letter or engage in any constructive forms with the families of victims,” Bazargan wrote in a Tuesday press release about the upcoming protest.

Since the protest group’s inception in October 2020, it has grown from a small number of victims and their family members to an established group of 12–15 regular attendees at hours-long, weekly Zoom meetings.

Director of Media Relations Scott Wargo released a statement in direct response to the protest movement in October 2021, a year after the committee first made the allegations against Mahallati.

“The College extends its sympathies to all victims who suffered at that time and continue to suffer today,” Wargo said.

Although the protest is being advertised as an Iranian women’s march and will take place close to International Women’s Day, its driving objective is to call attention to the allegations against Mahallati. The march will use the premise of the Islamic Republic’s treatment of women as a catalyst for conversation about the regime’s corruption and injustice, while naming Mahallati as one of the regime’s supporters in his role as an Iranian diplomat in the 1980s.

Ray English, Oberlin College director of libraries emeritus and Oberlin City Council member, has been following the story of the allegations against Mahallati since Oct. 19, 2021, when he read an opinion piece written by then-communications director of the Ohio Republican Party, Tricia McLaughlin, published in the Columbus Dispatch.

“I was concerned when I received at my home ad- dress a well-designed, full-color card that announced the November 2 protest,” English wrote in a message to the Review. “Both the Columbus Dispatch column and the card raised many questions in my mind. I be- came actively engaged with the issues when I offered a quote about my knowledge of Professor Mahallati to a reporter from the Elyria Chronicle Telegram who was covering the November 2 demonstration. His story led to conversations and email exchanges with the main parties involved and to my efforts to understand the complexities of the controversy.”

English’s efforts have led him to study multiple re- ports on the 1988 executions in Iran and archived U.N. documents, speak with both Bazargan and Mahallati, and read contextual sources about the historical events involved. Although English said his research is ongoing, his preliminary findings have led him to two central conclusions.

“The 1988 executions in Iran were horrendous,” English wrote. “The executions were clear violations [of] international human rights law. The inhumane treatment of the families of the victims also violated human rights standards. It’s clear that Ambassador Mahallati became aware of allegations about the executions from a U.N. representative who received information about them from Amnesty International. It is also clear that, as Iran’s ambassador to the U.N. who was represent- ing the position of his country, he cast doubt on those allegations. A key question for me is whether he knew about the executions at the time he made various statements about them to the U.N. He contends that he had no such knowledge.”

English also highlighted another part of Mahallati’s past, namely that he was imprisoned and tortured by his own regime upon his dismissal from his U.N. position in 1989.

“I think the Oberlin community should also know that Professor Mahallati was arrested, imprisoned, and subjected to harsh interrogation when he returned to Iran after being dismissed from his U.N. position,” English wrote.

According to an April 10, 1989 Washington Post article based on a leaked CIA report, Jack Anderson and Dale Van Atta outlined how Mahallati was arrested and allegedly tortured by the Iranian regime.

“According to the CIA, Montazeri was furious over the arrest of Mohammed Mahallati, Iran’s ambassador to the United Nations,” the article reads. “The Pasdaran, Khomeini’s Revolutionary Guard Corps, claimed that Mahallati was not faithful to the revolution. They arrested him in Tehran and tortured him until he had a heart attack. He was rushed to the hospital in critical condition.”

Neither Mahallati nor the College provided comment for this story.