Among the Ghosts, Geese, Bats, and Ladybugs: Love Letter to J-House

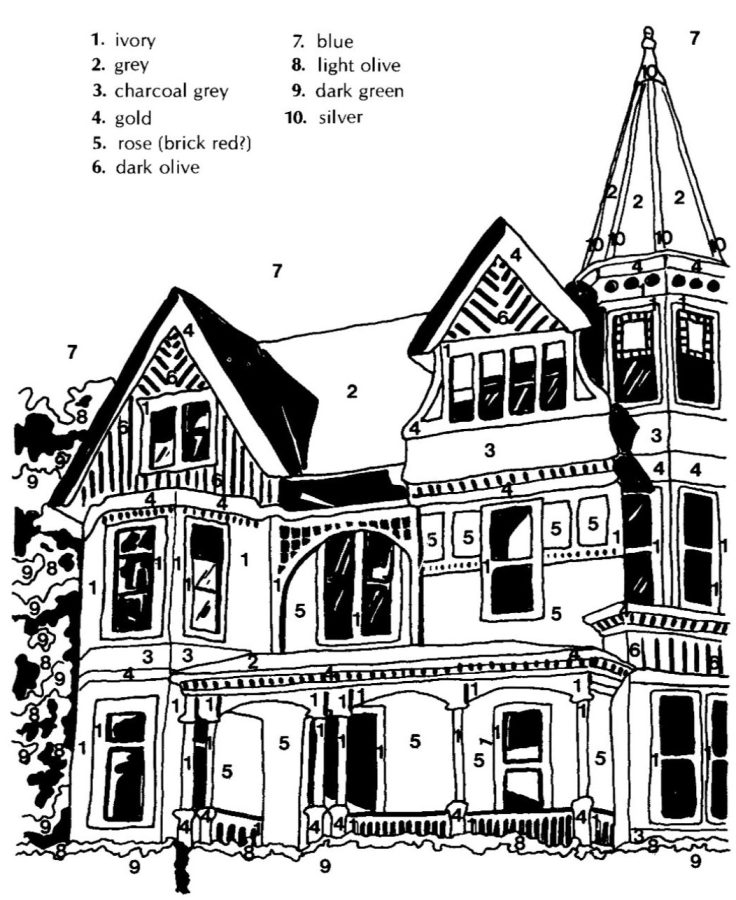

This Johnson House paint-by-number appeared in the Nov. 13, 1980 issue of the Oberlin Observer.

When I moved into Johnson House, it was freezing outside. It was February 2021, an isolating, pre-vax semester when everyone lived alone on a “de-densified” campus. Despite the chilly temperatures, I moved into a room infested with ladybugs. Their dead carcasses decorated the huge wooden window sills, and the living ones crawled through my sock drawer. How were there so many still alive in the middle of an Ohio winter?

But that’s just the thing about J-House: The whole castle-like structure seemed part of a living, breathing ecosystem larger than itself. I’d wake up each day to the distinctive honks from flocks of geese and feel like I was camping in the wetlands. At night, my friends and I would hang out on the fire escape and bats would flap around our heads, just at the corners of our vision.

J-House — adorned with its Queen Anne-style gables, bays, tower, and turret — is shrouded in mystical rumors and historical enigmas. The house was built in 1885 by railroad executive Albert H. Johnson, who enjoyed the lavish home for 14 years before he was killed on the railway. Legend has it that after he died, Albert’s wife, in distress, killed seven horses that lived in the barn behind the house. Some now believe that the home is haunted. According to a 1987 Review article, in a matter of weeks, several residents left their doors and windows closed and locked, only to come back to find a small, black bird in the center of their rooms with no clear point of entry.

Long after Mr. Johnson died, Charles Martin Hall bought the house in 1911 and gave it to the College, which used it for an experimental preparatory school called the Oberlin Academy. In 1916, the College repurposed it into a dormitory for women in the Conservatory, and it became the site of different types of shenanigans. In 1942, someone played a presidential prank on the residents of J-House, as reported in an article in The Oberlin News-Tribune.

“One of the cleverest hoaxes ‘dreamed up’ by Oberlin college students within the past few years had the campus ‘in a dither’ last Friday evening with the expectation that Mrs. Franklin Delano Roosevelt would spend the night at Johnson house, last outpost of ‘college civilization’ on South Professor street,” reads the March 19, 1942 issue.

The News-Tribune story goes on to tell of the girls, mostly first- and second-years, busying themselves with preparing and tidying the house until eventually realizing they’d been pranked at around 10:30 p.m.

During my own time at J-House, I don’t remember any pranks, but the idea that it was a community — even though large community events were barred because of COVID-19 — somehow remained. Though I was initially afraid I wasn’t Jewish enough for a “Hebrew Heritage Program House,” I soon learned that while there was community in J-House, most of it didn’t really have to do with Judaism. In fact, Hebrew Heritage House was not housed in J-House until spring 1988, having previously been located in Shurtleff Cottage. Before this point, in the ’70s and ’80s, J-House was home to the Farm Co-op; members built its solar greenhouse by hand in 1977.

“We had the garden right there, and at the end of every day, it was part of our chores to go garden and harvest,” said Rick Ruggles, OC ’78, who started the greenhouse during his time at Oberlin. “There were a lot of folk musicians that lived there — banjo players and fiddlers. I actually picked up the mandolin while I was there.”

In those days, the intricate building was devoid of its distinctive colorful exterior; instead, it was painted entirely white. Lorain County Regional Planning Commission planner Steven McQuillin, OC ’75, came up with the idea of restoring the building to its original colors in 1977 and convinced the College to apply for a federal grant to pay for the ordeal. After combing through the Oberlin College archives, McQuillin found no account of the house’s colors in 1885, so he gathered paint chips from the exterior. The Allen Memorial Art Museum’s Intermuseum Conservation Association scrutinized the chips under a high-powered microscope.

“The layers of paint in the cross-section reminded me of tree rings,” McQuillin told The Oberlin Observer in 1980. “In the nineteenth century, Victorian homes were not painted all white, as they tend to be today.”

The best part about living in J-House, though, was not coming home to such a beautiful, colorful building. It was not the large room I had all to myself, or the fire escape makeshift porch, or the friends I had living down the hall. Weirdly, the best thing was how far away J-House is from campus. Most of the time, I move too fast and get overwhelmed too easily, always misjudging and telling myself I don’t have enough time to go on a walk with friends or bike through the park. But living in J-House, just slightly far away enough to be inconvenient, was a reminder to take things slowly, like just walking past Plum Creek on the way to class.

“I think there was something magical to this space,” said Vanessa Filley, OC ’98, who lived in J-House two decades before me but felt the same thing I did. “I thought dorms were a nightmare, [but J-House] had a much smaller sense of community and intimacy. It was a house, so it felt more like a home. There was a huge compost pile out back and then there was the proximity to the Arb. Just kind of being a little bit separate from campus — I rode my bike a ton — I liked that slight remove.”

Last year, former Dean of Students Meredith Raimondo sat down with the residents of J-House to tell us that the building needed repairs to the roof. The repairs were estimated to cost at least $500,000 and Raimondo said the College might need to close the space indefinitely. Raimondo assured us not to worry, and that the Hebrew Heritage House Program would be moved to a different dorm, maybe on North Campus. Of course I know it’s important to continue the program house, but the idea that J-House’s specialness came from its designation as a place for Jewish students seemed laughable — half the students living there weren’t Jewish at all. I couldn’t help but worry that something would be lost.

This year, in the employment shuffle in Residential Education and the Office of Student Life, discussions around J-House have shifted. Assistant Vice President and Dean of Residential Education and Campus Life Auxiliary Services Mark Zeno assured the Review that there are no plans to close J-House soon.

“My understanding right now is that J-House is slated for renovation,” Zeno said. “There’s not to be any changes of emptying that house or closing that house down at this time. They are going to move forward with the needed renovations in that area.”

Bizarrely, even though it was a semester of pandemic-induced disappointments, the semester I lived in J-House is the moment of college that I will always be the most nostalgic for. There were no mysterious black birds in my room, but the sense that something warm, benevolent, and spiritual was watching over me followed me throughout the semester. Every deadline I wasn’t prepared for seemed to get pushed, my broken bike suddenly began working again, and the boy I had a crush on had a job working in the garden behind J-house so I would run into him all the time. Whatever it was, everything seemed to work out for me. Maybe it was the ghost of a railroad multimillionaire, maybe it was G-d, or maybe it was the house itself.

J-House nurtured hundreds of schoolchildren and a nursery of 371 evergreen seedlings at Johnson House barn during the 1940s. It has survived multiple attempts to demolish it and a minor fire in the summer of 1944. It is home to the bugs and the bats and one rat in my room who ate my Oreos. I hope that it will continue to look over students for years to come.