“Frack Yes!” Talk Incites Protest

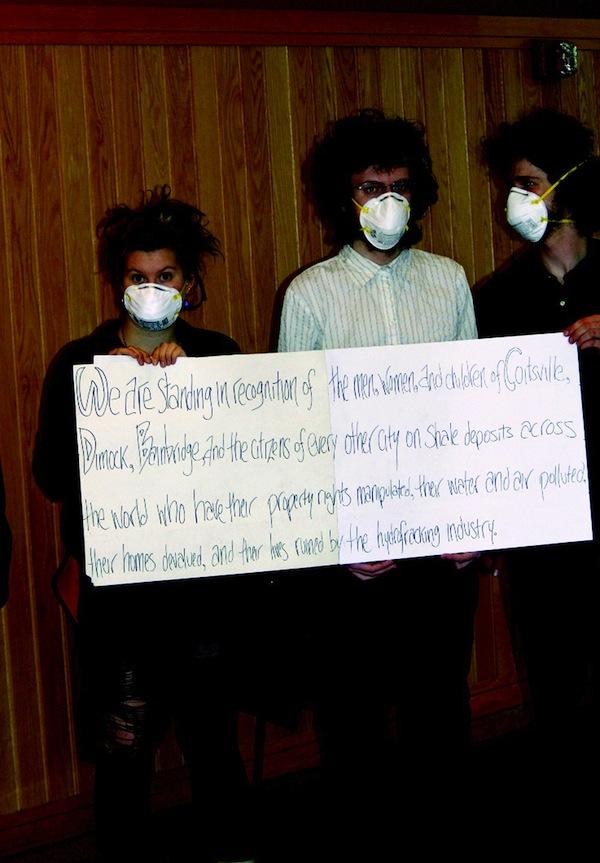

Students opposed to fracking, or hydraulic fracturing, expressed their dissent at Wednesday’s lecture titled “Frack Yes!” with Daniel Simmons, Director of Regulatory and State Affairs at the Institute for Energy Research.

April 13, 2012

Hydraulic fracturing advocates and opponents met Wednesday, April 11, for a screening of Gasland followed by a lecture titled “Frack Yes!” given by Daniel Simmons, director of regulatory and state affairs at the Institute for Energy Research. Students in the audience waved red flags in silent protest and snickered audibly throughout Simmons’ speech. Associate Dean of Student Life Adrian Bautista at one point stopped the speaker and implored the audience to express their dissent within preset parameters.

Preceding Simmons’s lecture, a number of students opposed to fracking screened the documentary Gasland, by filmmaker Josh Fox, which explores the effects of fracking across the United States. Many students protested during the lecture by waving red flags when they disagreed with a point that Simmons made, passing out anti-fracking pamphlets to audience members attending the lecture, or spontaneously crying out during the lecture.

Students opposed to fracking, or hydraulic fracturing, expressed their dissent at Wednesday’s lecture titled “Frack Yes!” with Daniel Simmons, Director of Regulatory and State Affairs at the Institute for Energy Research.

“[Tonight’s opposition was] characteristic of Oberlin,” said College junior and president of the Oberlin College Republicans and Libertarians Nick Miller, who organized Simmon’s talk on campus. “I didn’t expect any more or any less. … We did grill the guy for an hour and a half. That’s quite a long time and it just doesn’t let up. I think it’s childish. … [However], I honestly think that waving red flags was a brilliant idea. The rest that went along with it – the few members of the group that were yelling louder and louder — most people don’t care what they have to say. … That’s less productive. But I always like silent forms of protest because I think they’re creative and I welcome them.”

Simmons began his lecture, which was part of the Ronald Reagan Political Lectureship series, by talking about the history of oil and natural gas production.

“The issue of hydraulic fracturing is an issue that deals intimately with an energy revolution that is occurring in this country today,” said Simmons. “Since the 1970s, oil production in the U.S. has decreased along with natural gas production. But that trend has reversed over the past few years and that is because of hydraulic fracturing. From 2005 to 2011, natural gas production increased by 22 percent and oil production increased by 14 percent since 2005.”

Opposition by anti-fracking students began when Simmons began discussing environmental issues connected to fracking. “Here is the big picture on the environmental issues,” said Simmons. “There is not one confirmed case of hydraulic fracturing contaminating groundwater. It has been used for 60 years. … The EPA [Environmental Protection Agency] has had to retrace its steps. Just Google it. Google the news. It’s not that hard. It’s happened in the last month. … The EPA is going back and doing more testing in [the case of] Pavilion, WY to try and understand because honestly they didn’t do very good science.” During the question-and-answer session, when asked about how Simmons would respond to testimonies of people who have gotten sick after hydraulic fracking began in their towns, Simmons said that he believed the claims should continue to be investigated.

“I think it’s very concerning and I think it’s important for the relevant regulatory bodies — the state as well as the EPA — to look at those issues and to see what we can find. … And so far, neither the state regulatory bodies nor the federal regulatory bodies have found that connection. Could there be one? Yes. And I think it’s important to continue to monitor,” said Simmons. Simmons went on to say that, in his opinion, the benefits of fracking outweigh the negative effects.

“All actions that we take have consequences. It’s as simple as out in the California desert building large, commercial-scale solar-powered facilities. Those come with environmental consequences. It that case, you’re covering the desert with solar panels. It’s ugly … it impacts the desert tortoise, which is a threatened species,” said Simmons. “When it comes to something as hydraulic fracturing, what I believe is the downsides can be mitigated enough so the benefits far outweigh what the downsides are … I would much rather live in a world where gas is cheap.”

Miller, a libertarian, agreed with Simmons on the importance of cheap energy.

“Energy is fundamentally the most important thing that any economy produces. We can’t just sweep it under the rug, just because we don’t like it,” said Miller. “The economic benefits [of fracking] cannot be questioned. Cheaper energy doesn’t just help Americans. … This is a global market. … Fracking itself, as a technology, is quite brilliant. Casings can fail. The fracking technology didn’t fail, it’s the casing that failed and you can fix those problems.”

Many, like College sophomore Alice Beecher, who helped organize the screening of Gasland, disagree with this perspective.

“It’s frustrating. It’s something I’m familiar with: A lot of people trying to figure out ways to misinform the public using this idea that this kind of thing is a capitalist enterprise and is going to create all these jobs for everybody and is more sustainable than oil, which isn’t true,” said Beecher.

Other opponents of fracking, like College junior Samuel Rubin, who helped organize the protest to Simmons’s lecture, believe that fracking is part of a far more fundamental environmental problem.

“Fracking is just one manifestation of a larger problem, and that problem is climate change,” said Rubin. “But even more profound are the human rights issues and abuses that occur when you frack. The fracking industry is holding a gun to our head and pulling the trigger. … They are poisoning our water; they are ruining our land; they are destroying our lives. … This is no longer an environmental issue about global warming, this is a profound human right abuse.”