Print Publications Shed Light on Generations of Oberlin Activism

Photo courtesy of Oberlin College Archives

Oberlin has been home to a number of political publications over the years.

Before the internet, print was the primary means of spreading ideas and information. Campus groups or individual students who wanted to bring attention to an issue, gather support to a cause, or educate the population on a certain topic turned to the printing press. In the form of magazines, zines, pamphlets, newsletters, and newspapers, printed materials were a large part of discourse on campus. Many of the publications they created are saved in the Oberlin College Archives, and give us a window into the beliefs and ideas of generations of past students.

The oldest political publications available in the archives date back to the World War I era. The Oberlin Critic was created in 1922 to promote progressive thought and policy on campus through both serious and humorous pieces. Articles in their first issue criticized the school’s policy of requiring female students to have a chaperone in many circumstances and called for more freedom of discussion in the classroom, labeling professors at large “The Autocrat of the Lecture Table.” Another interwar publication, The Vanguard, was more left-wing. The Vanguard, of which records exist from 1934 to 1935, reported on international issues, labor conflicts, and other current events, and espoused anti-capitalist and pacifist views.

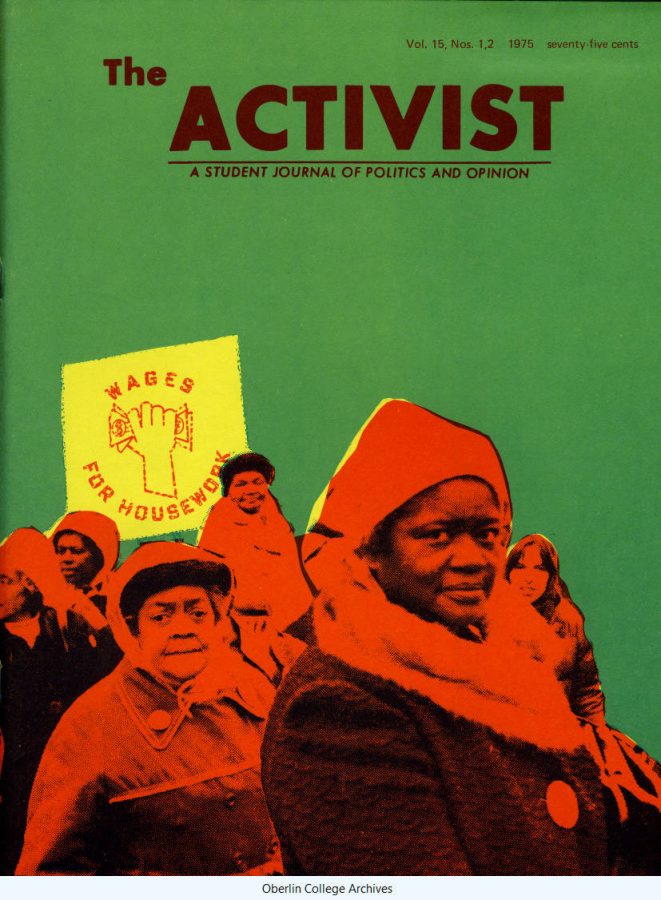

The 1960s ushered in a new era of activism on campus, and the material published by students reflected the change. One of the many new publications in this era was The Activist, the first issue of which was released in the fall of 1960. The Activist began as a newsletter for the Midwestern Student Coordinating Committee, an organization comprised of representatives of 24 Midwestern colleges and universities with the purpose of coordinating direct action for civil rights amongst students in the region. The first issues were short typewritten newsletters that reported on the actions of the Midwestern Student Coordinating Committee and other affiliated student activist organizations, and national events like the arrest of Martin Luther King Jr., as well as provided editorials on current issues, primarily centering around the ongoing Civil Rights Movement.

By 1961, the publication had ended its affiliation with the Midwestern Student Coordinating Committee and took the form of a magazine. With the change in format, The Activist published longer and more scholarly pieces, like “The Philosophy of Activism” and “The Meaning of Dissent,” both from 1961, in which the writers gave their worldview on the role of activism and how it was to be employed, or provided in depth analyses of current events. The publication proclaimed itself a “journal of the new student awakening” and embraced the politics of the New Left. “The publication is independent of any organization, al- though we are associated with Students for a Democratic Society in more or less an ideological sense,” the mission statement published that fall read. “We both desire to see the extension of the democratic process, so that each individual might have the chance to develop to his fullest capacity, free from fears of war, hunger; free to hear all sides and form opinions in an atmosphere of tolerance and sanity.”

The Activist did not shy away from pushing the envelope. Their 1969 special issue on Black literature and poetry was rejected from the printers on grounds of “dirty words” and “dirty ideas,” according to an editor’s note. The editors typed up the issue and had it mimeographed by the Oberlin College Buildings and Grounds department, but after printing the department refused to give the students the finished copies. In the end, the issue had to be published with two poems removed.

Other publications on campus during the counterculture era were even more provocative. The self-proclaimed Review Rip-off used the Review’s font in their masthead that read “What the Review Wouldn’t Print” in their first issue in 1972.

“We have been waiting to see what the Review has to say about women’s issues,” reads the mission statement entitled “No More Diplomacy” read “Well, we have gotten tired of waiting, so we’ve decided to bring you our own version. While we realize that we have inconvenienced and perhaps offended some, and annoyed many others by our action, we do not apologize. We have tried diplomacy, and we have decided that liberalism is bunk.”

Over the decades that followed, a multitude of new student publications emerged. Some campus publications were published by organizations like Oberlin and South Africa, a single issue newspaper style publication released in 1979 by the Oberlin Coalition for the Liberation of South Africa educating students about apartheid. Other publications centered around the perspectives and activism of certain identity groups such as The Collective, a publication that featured the writing of people of color at Oberlin. It ran articles on international, domestic, and Oberlin-specific events, as well as poetry. Some of these publications were given away in public spaces around Oberlin. Others such as Alternatives, founded in 1975, relied on subscriptions.

Former editor of Alternatives Suzanne Ludlow, OC ’81, told me that at the time she worked for the publication, the audience was largely outside of Oberlin.

“We were trying to [publish Alternatives] as something that represented Oberlin being thought- ful about political issues,” Ludlow said.

Not all publications had an explicit agenda. Some functioned as a forum for students to share their own views.

“I think in particular we [were] interested in trying to explore different angles of issues, because Oberlin can feel like an echo chamber,” Avi Lipman, OC ’96, who founded The Voice, which covered current events through student opinion pieces. “We wanted to have pieces on political issues … trying to explore the different angles in a way that could encourage meaningful debate.”

Both Ludlow and Lipman stressed the importance of print publications in the era before the internet. To spread ideas within a community even as small as Oberlin’s campus, printed material was a necessity. Ludlow said that for any college organization, a good portion of the money they received from the school went to publicizing their cause through publications.

“Publications were everything,” Ludlow said. “On campus or in any community, you would have the major newspaper… and then a whole lot of alternative press, whether it was in newsprint format, or mimeographed newsletters. That is what people shared with each other… People would go door to door with them in places.”

Kira Zimmerman, OC ’19, who worked to catalog and summarize student publications on campus for the archives, pointed out another power of print is its ability to reach audiences beyond social divisions.

“Remember [Oberlin’s campus] was fairly segregated by gender well into the 20th century,” Zimmerman said. “So many of the publications would have reached male and female audiences… pretty individually.”

The number of student publications has substantially decreased since the rise of the internet, as is evident through the materials available in the archives. Social media and digital publications gave a new, more efficient way for student organizations and individuals involved in activism to reach out to the community and spread awareness to causes. Still, the publications of generations past remain in the archives as a testament to generations of past activist work.