On the Record with Richard Powers: Novelist, Advocate, Commencement 2023 Speaker

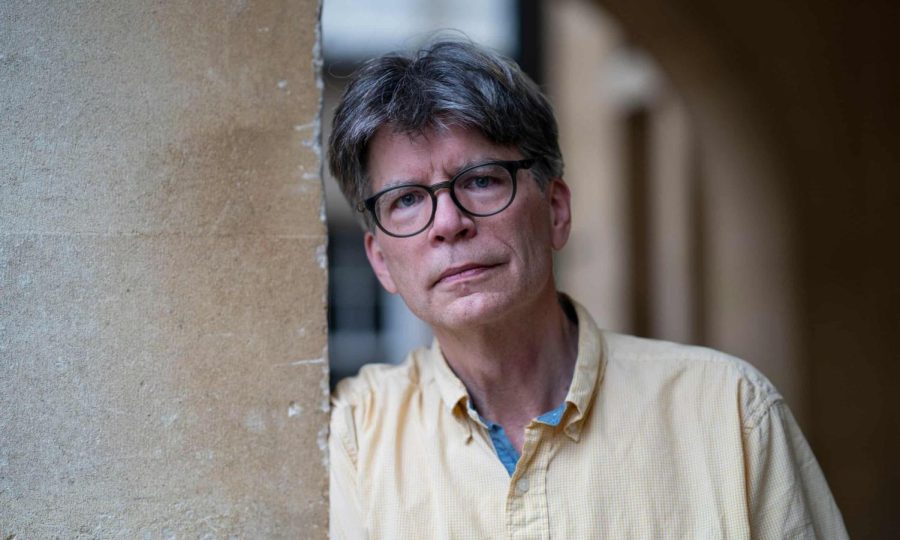

Photo Courtesy of The Guardian

Novelist Richard Powers was selected to be the Commencement 2023 speaker.

Richard Powers is a novelist with a background in environmental and computer science whose work focuses on the relationship between humanity and the natural world. He has won numerous awards, including the 2019 Pulitzer Prize in Fiction for his novel The Overstory. Powers will give the Commencement address at the class of 2023’s Commencement ceremony this Monday and will also receive an honorary Doctor of Humanities degree.

I know you were a Physics major in college; what got you into writing fiction?

I had a very influential professor of literature whose honors seminar I took as an undergrad. He was an extremely powerful thinker, and the amount of insight that he could draw out of a text was so impressive. This idea that storytelling was deep and rich, and deeply illuminating about the tellers and listeners, that was all very seductive to me. While I did have very specific skills — I was very good in math and problem solving and analytical tasks — I also took a great deal of pleasure out of connecting things, out of getting a big picture.

You spent some time living abroad in Thailand and then in the Netherlands. How do you think that’s impacted your writing?

The act of writing is the attempt to see the world from perspectives that aren’t yours, and that’s also what traveling and living in other places does. The moment that you are displaced from your own culture and your own comforts and your own set of assumptions into a place that operates by very different rules and according to very different values, you have to completely rethink what you believe about the world, and it makes you see yourself in a different light. When I moved to Thailand at the age of 11, I was going from a pretty affluent suburb of Chicago and moving to a city on the other side of the world. All of a sudden, everything that I knew about the world was wrong, and I had to relearn it. When I came back to the States, ostensibly my own country, I was really an outsider at 16. I could move about in that culture, I knew the rules, but I was kind of looking at it from the perspective of somebody who had very different experiences, and I think that’s the first step of being a writer.

In 2019, you won the Pulitzer Prize in Fiction for your novel The Overstory. Could you talk about what inspired the novel, and what it’s about?

I was teaching at Stanford University after teaching at the University of Illinois for many years, and living in Silicon Valley, it’s a very intense, very utopian, technologically infatuated culture. To get away from this, Iʼd go up into the Santa Cruz mountains just between Silicon Valley and the Pacific and hike in the forests up there, and many of those set-aside forests were recovering redwood forests. When you see a 1,500-year-old redwood tree that’s older than Charlemagne and that’s as wide as a house and as tall as a football field, it changes your way of thinking about time, and changes your way of thinking about our place in the world and about the agency of life. I was suddenly confronted with the evidence of what we human beings have done to the non-human world, and the evidence of how powerful the non-human world was and how deeply we depended upon it. I think it was that awakening that led to this idea that I could write a book that wasn’t simply about humans, and had non-human characters, and explored this kind of forgotten dramatic reality — that we humans are here by virtue of all the other living things that we share the earth with, and that we’re a relative latecomer.

In 2017, you wrote an opinion piece for The New York Times titled “Keep America Wild” about Maine’s Katahdin Woods and Waters and the plans to develop them. How do you think this piece was in conversation with The Overstory?

It was written at a moment where, after some years of gradually learning that we could not dominate and endlessly exploit and defeat the non-human world, we were instead starting to slip backwards into a much more human-exceptionalist and triumphalist and separatist program all over again. This piece was basically trying to oppose that moment, and like The Overstory itself, it was trying to take the long lens and say any species that tries to go it alone is going to end up with the other 99 percent of the world’s species that have already gone extinct.

Since then, you’ve published another novel, Bewilderment. What is it about, and what inspired it?

Bewilderment is the story of a father who is raising a neurodivergent 10-year-old boy by himself after the death of his wife, and the boy suffers from extreme forms of eco-trauma, as I think a lot of young people do. Basically, this is the story of a father who has to acknowledge and tell his son, “Yes, the human world has gone crazy. And no, I don’t know the answer to what to do about that.” It was inspired very specifically by my own experience with young children who were suffering from a bewilderment at the insanity of the way that the industrial world is treating the living world.

Do you think that you play that role as an author, having to bring attention to the climate crisis in a way that won’t freak people out?

In The Overstory, Patricia Westford, who is kind of the moral center of the book, is tasked with giving a speech at a climate conference. She’s wrestling with this idea that she’s expected to say something that’s true and useful and hopeful, not defeatist, not overwhelmed. It’s very, very difficult to juggle those things, and when you write a book, if your intention is at all to describe who we are and where we are and what we’re doing, it’s very difficult to be all those three things.

What is it about Oberlin that connected with you and made you say, “Yes, I want to be the Oberlin Commencement speaker”?

I have had numerous friends who are Oberlin grads who have played a role in my own formation and the formation of my own understanding of the world, as a young person and even in middle age and now in old age. My own novels have been so deeply tied up with American history and the crises of American histories, the various wars for realization and liberation of the marginalized and oppressed populations in this country, and Oberlin has been very much at the forefront of those struggles for a long time.

I’m very excited about giving the speech, and it was a chance for me to go back and remember what it was like for me to be 21 or 22 and graduating from college. It was just a real pleasure to go back and try to recall that as precisely as possible, and try to think of what words might have been useful to me to hear at that moment.