The domestication of coffee is believed to have started in the Horn of Africa, although we still can not pinpoint the precise area and time where that craft began. Still, the plant’s historical prevalence in the Eritrean and Ethiopian plateaus, their inhabitants’ rich tradition of coffee rituals, and folklore on the origins of brewing the drink suggests that the plant was domesticated in the Horn of Africa more than a millennium ago. Traded from the coasts of present-day Eritrea, Djibouti, and Somalia across the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden to Yemen, coffee brewing was refined by Yemenis (the English term “coffee” is distantly transliterated from the Yemeni Arabic, qahwah). The British Coffee Association claims that 2 billion cups of coffee are consumed daily worldwide, making this Horn of Africa-originated and Yemeni-perfected drink a global obsession.

Across the Horn of Africa, the coffee ceremony is a typical daily ritual among the diverse groups of people who roast, ground, and brew the coffee beans of this intriguing plant in a special clay pot on a charcoal brazier and served in tiny china cups referred to as “finja” or “qahwa cups.” The elaborate coffee brewing ritual, sometimes accompanied by burning frankincense and myrrh to create a fragrant atmosphere, is a centerpiece in most Horn of Africa households, where every family member gathers for an hour to drink coffee, converse, and share blessings. No one is allowed to move before the hour-long ceremony of at least three rounds of coffee refills culminates; time slows down, calmness abides, and spirit and body are replenished by the stimulant caffeine in the drink.

In my home country of Eritrea, the traditional coffee ritual is complemented by the European-style espresso café galore, remnant businesses from the Italian colonial era of the 20th century. The indigenous and the foreign coffee traditions are vital lifestyles of Asmarini (Asmara urbanites) who use café establishments as their extended living rooms: communal spaces where students finish assignments, romantic couples go on dates, nosy uncles and aunties sit for hours staring as passersby and clients through the glass windows (it’s a small city, everyone knows everyone), and lone folks ask to share a table with strangers, soon to be new friends.

One of the biggest culture shocks I had when I came to the US was the lack of accessible and conducive third places. In his 1999 book The Great Good Place, American sociologist Ray Oldenburg coined the term “third place” as a place outside your home or work where you can relax and hang out. In an individualistic and isolationist American society, coffee shops are a welcome venue to be in the company of a community. In Oberlin, Azariah’s Café and Slow Train Cafe serve as links to my Asmarini café culture. The spacious seating area at Azzie’s and the welcoming faces of my Obie friends and acquaintances are what I adore the most. I love interacting with the skilled baristas, several of them fellow students who make beautiful latté art. Some of them, I notice, start basic and then go on to make ornate touches over just a few weeks. I even learned to notice and admire the different espresso tastes from one café craftsperson to the other distinctly. Another favorite satisfaction I get from the café is seeing the community of fellow café enthusiasts who love starting their day with an “umff” of caffeine to energize their bodies.

However, that cherished interaction seems missing recently, as Azzie’s is now exclusively mobile order only. This means no more waiting in long lines, no interaction with the attending person to take your personalized orders, and fewer faces of eagerly waiting coffee-guzzling comrades; you just find a set of assorted to-go order cups and compostable boxes with the baristas’ seeming hectic and scrambling to catch up to a barrage of incoming mobile orders, while at the same time being frustrated with loads of unclaimed orders lying on the fussy steel table.

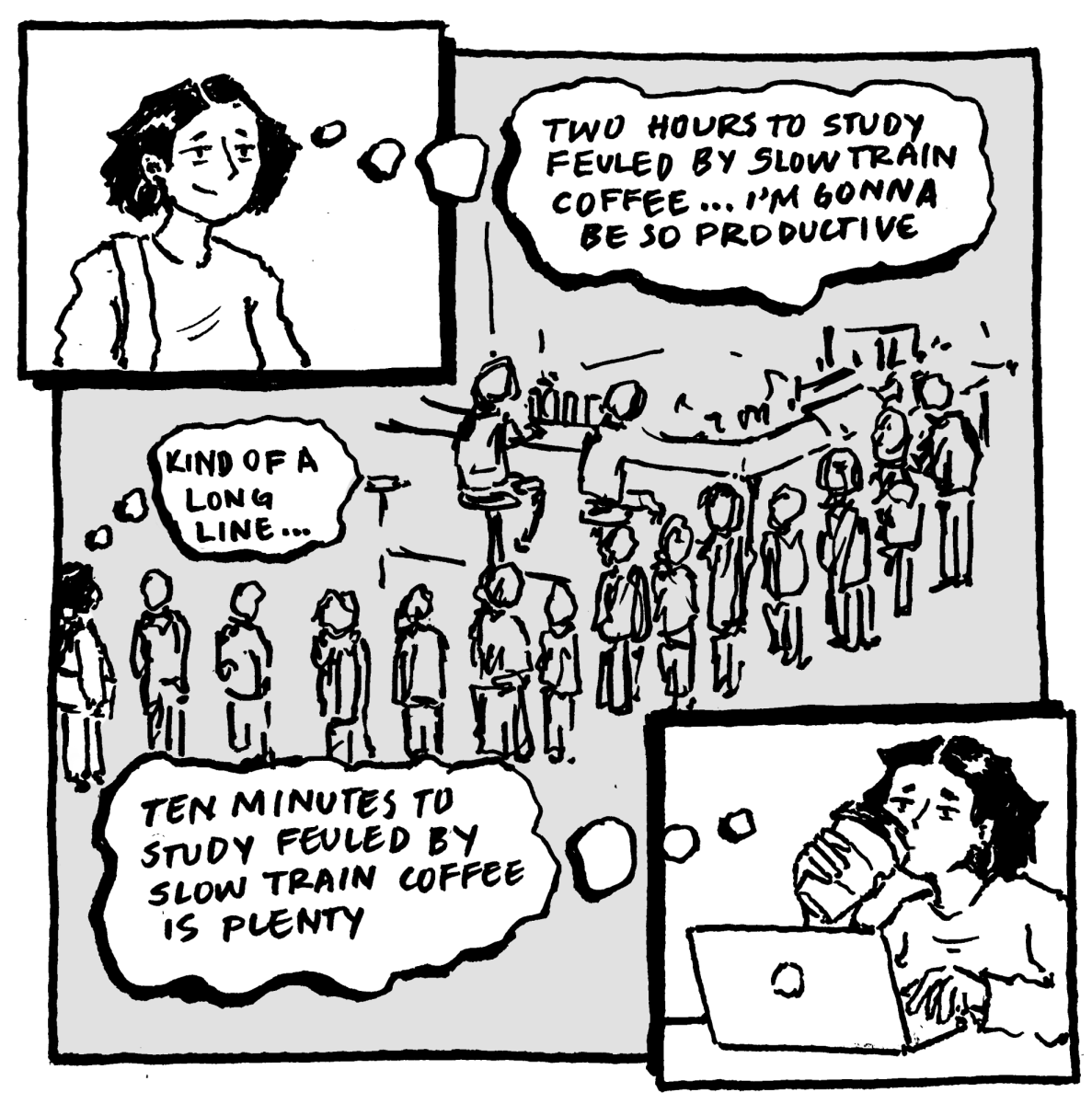

The transition to mobile ordering came via AVI Food system’s initiative to make food ordering smooth, fast, and remotely accessible, and it is a brilliant way to enable students to order ahead of time and avoid long lines and wait times. But during busy hours, the exclusive mobile order system makes wait times unpredictable and slightly inefficient as you must open a new order per item. When ordering at the register was available, students would infer from queue lines and decide whether to wait or just return after classes.

For some of us, café-going is not just a mere transaction to get food, but a ritual to get the quasi-panacea that is coffee from people who make it with dedicated skill. After all, food making is lavoro fatto per passione or a labor of love. It would be greatly appreciated if our friends at AVI Fresh and Azzie’s could reinstate the option for in-person ordering at the register so those of us who regard coffee as more than a mere beverage can continue to enjoy the process, not just the product.