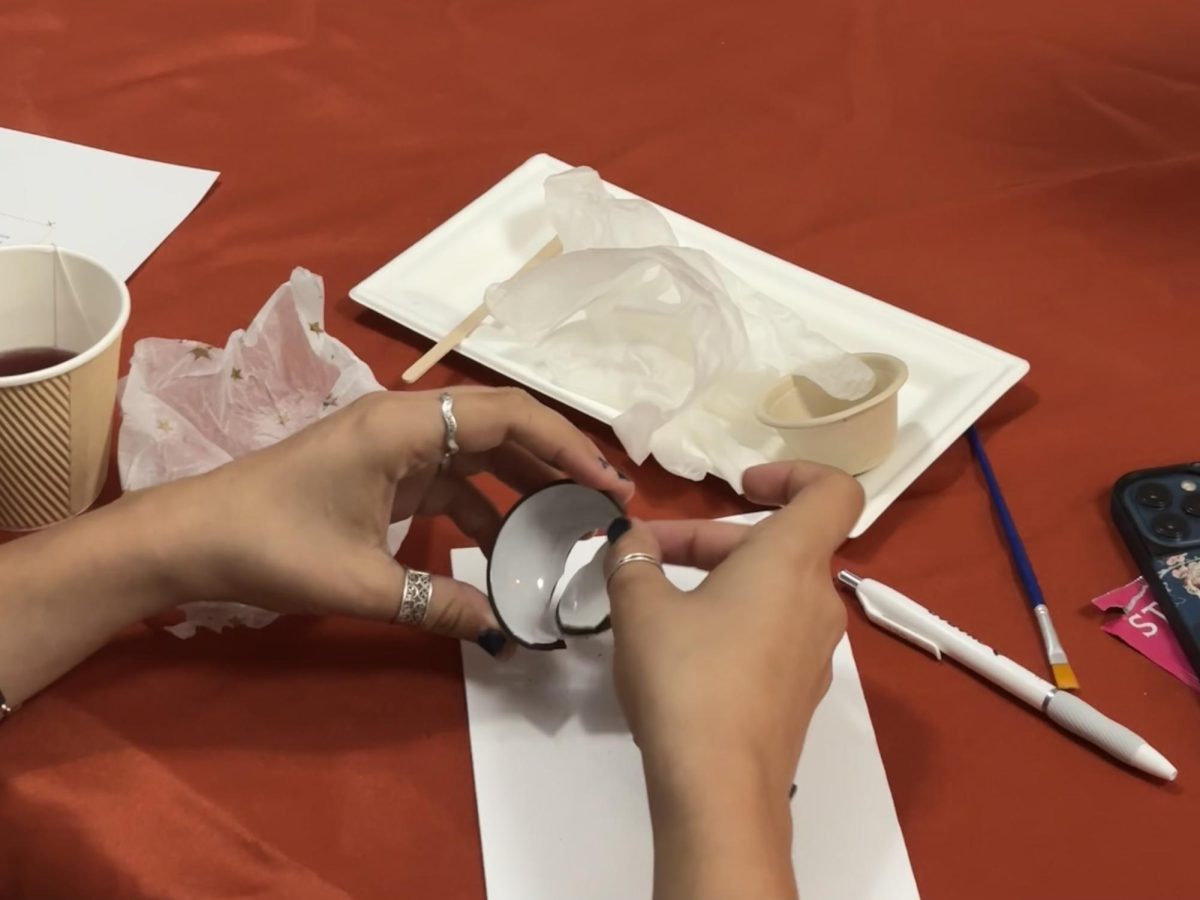

Though it may not sound like it at first, raised gold strokes that piece together a shattered vessel can invite introspection. Co-Director of Chabad at Oberlin Devorah Elkan led students in a kintsugi workshop last Tuesday. Kintsugi is a Japanese art form that involves using gold lacquer to mend broken pottery, and the act of making something new out of broken pieces is perfect for metaphors.

At the workshop, a dozen untouched miniature charcoal colored bowls with smooth white insides were placed in front of each attendee. Participants were asked to first draw a shape that they felt represented them on a piece of folded white paper and had the option to write a brief blurb to go along with it. Within the shape, they drew and wrote down weaknesses or things that they wished to let go of, as well as strengths they hoped to maintain.

College second-year Sophie Silverman remarked on her deep appreciation for Elkan and how she is able to bring unique projects to Chabad and relate them to the teachings of Judaism.

“I thought it was cool to take an art project that I wouldn’t have necessarily associated with something like Rosh Hashanah and turn it into an elevated thing,” Silverman said.

Silverman frequently attends Chabad events and invites her non-Jewish friends to join her because of how the organization infuses meaning into a variety of activities.

“Devorah was saying a lot of very interesting things and giving advice by using a metaphor about clothes in your closet, [asking] whether you really need them and [relating that to] what your soul really wants versus what your head wants,” College second-year Luna King-O’Brien said.

This workshop was the first of its kind, with more introspective “art and soul” workshops planned for the coming year.

“One of my favorite parts is seeing people’s reactions when their vessel finally breaks,” Elkan said. “People know that they’re going to, by and large, be able to glue their vessel back together. [I hope they] can take that small experience of, ‘I can put this little piece of pottery back together’ and extrapolate that to other elements of life, … realizing that no matter how it breaks, if it breaks into a bunch of little pieces, or if it breaks into two big ones, I still can [put it back together].”

Though breaking the pots, or “vessels,” was challenging, each participant succeeded. This represented letting go of control and moving forward from what doesn’t suit them anymore.

“Every person in this world is a vessel,” Elkan said. “The whole purpose of the vessel is to contain and to pour out.”

That the vessel will eventually crack or break is inevitable, but it’s in the individual’s hands to piece it back together. Elkan touched on how important this was in relation to the upcoming Jewish new year.

“I think the vast majority of New Year’s resolutions don’t actually get done,” Elkan said. “I was kind of thinking about what would be a nice exercise to have a few minutes of introspection, [to] really think about who I am as a person — what are my strengths, what are my weaknesses? When [it comes] to Rosh Hashanah and I make a New Year’s resolution or I think about what I want my new year to be, then maybe it can come from a more authentic place of oneself, rather than just grandiose, ‘Oh, I’m going to do this.’ [That type of resolution feels] so disconnected from who I am and what I need to be doing, or what I’m capable of doing, that therefore it never happens.”

Elkan noted that this event was inspired by her experience of becoming a trained life coach. The event also emphasized the importance of sharing meaning and guiding others to find the meaning in their own lives.

“I think that my training and my experience in becoming a life coach was the impetus to coming up with something like this to do here at Oberlin,” Elkan said. “[I’m] on a personal journey, thinking about some of these things for myself, and [I thought] ‘Hey, maybe these are concepts and things that we can all think about on a communal level.’”

Chabad events typically help Jewish students find meaning in religious gatherings such as high holiday services or Shabbos, but this event and future art-related workshops can guide both Jewish and non-Jewish students to reflect on themselves as they produce a piece of related art.

“I hope it’s impactful in some way,” Elkan said. “I find that art in general, or … doing something with our hands or physically experiencing something, allows us to internalize things. I find that having the physical thing helps [to] solidify [learning].”