On Saturday, Oct. 5, Drew Matott, co-director of Peace Paper Project and master papermaker, will lead a demonstration of papermaking in the Mudd Center Contemplation Garden. Students will be able to turn articles of clothing into paper, expressing their creativity and sentiments through art. Matott will provide clothing from Ukrainian refugees and U.S. military uniforms, but students are encouraged to bring their own clothing to transform into meaningful art.

In his last semester of studying printmaking at Buffalo State College, Matott took a papermaking course that redefined his perspective on the art form.

“As I was going through the papermaking and printing processes, I realized that by using my own clothing, I had a relationship with it,” Matott said. “This is my shirt. This is my clothing. I had a story here to tell. It started to change some of the ways that I treated my prints.”

Matott discovered that papermaking was more than a technical skill; it was a way of intimately connecting with distant memories. Matott’s father, an antiwar activist, poet, architect, and philosopher, passed away when he was young. His family’s main method of communing with his late father was to go into his old study with a cardboard box full of his items, including a pair of blue jeans and one of his work shirts among other apparel. Inspired by his newfound passion, Matott decided to make paper out of these clothes.

“I called up my brothers, my sister, and my mom,” Matott said. “We all sat around the dining room table and took scissors to my dad’s clothing. We cut it up and shared memories about him, and it was really meaningful for us to come together in this way. That was really powerful — the cutting up of the material.”

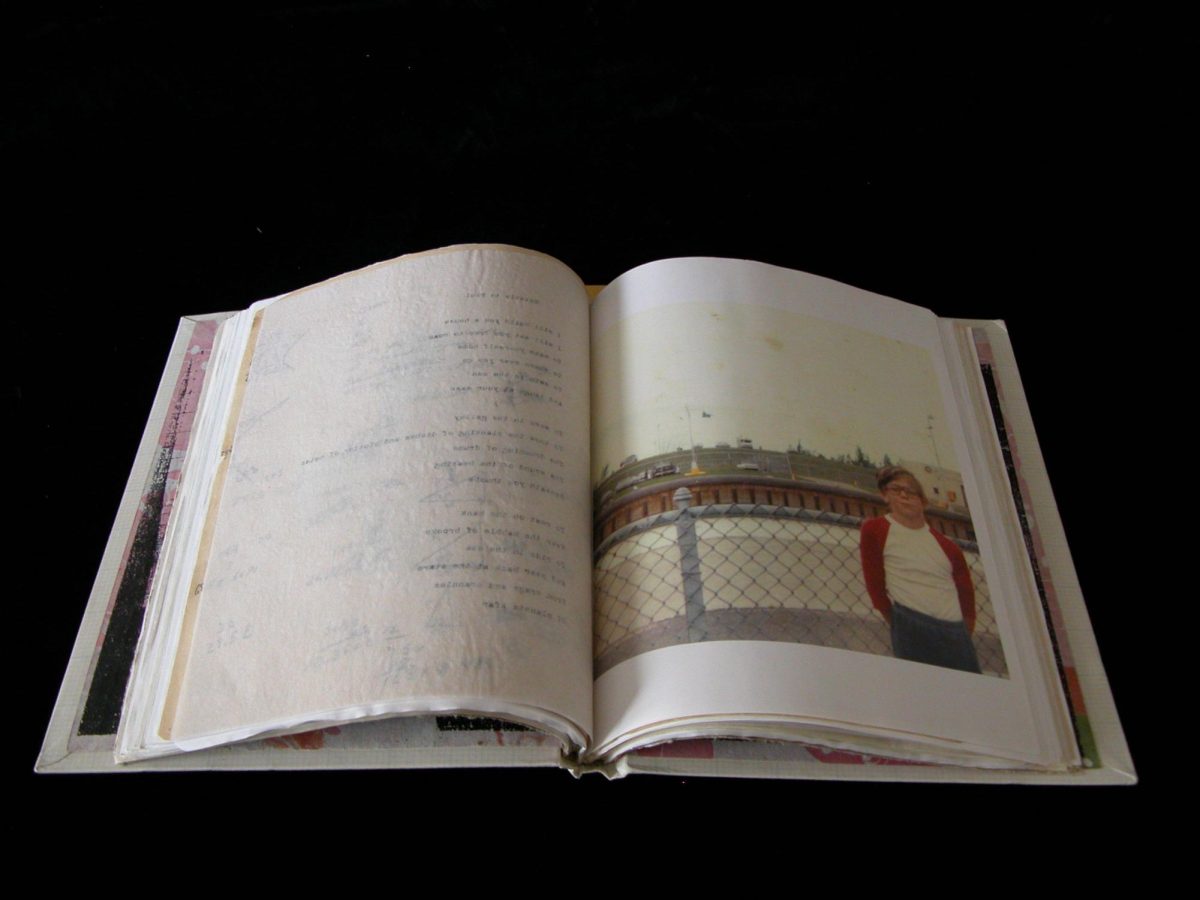

After the initial papermaking process, Matott crafted an edition of 13 books from scans of his father’s old drawings and letters — one for each member of his family. One recipient was his father’s brother. Although his father and uncle were once close, their relationship was severed after they were both drafted to fight in Vietnam. Their outlooks differed greatly. HIs uncle felt a sense of duty to defend American democracy by fighting in Vietnam. While his father felt the same sense of duty, he adhered to his ideology by burning his draft card and joining the antiwar movement. Nonetheless, Matott called him to tell him about the book.

“I was really nervous,” Matott said. “He was sitting at his desk, and he opened the book. The end pages of the book are 10 portraits of my dad, and as soon as he saw the portraits of my dad, he slammed the book shut and started to cry. He came through after a few moments and shared memories of him. When my father was killed, my uncle had this regret and remorse over patching up their relationship. Ever since that experience with my uncle, every time I went home on holiday, he would take my dad’s book and he would tell a story about a photograph, read a passage of a poem, or share a memory of my dad.”

Through this experience, Matott realized the profound effect that papermaking could have on building relationships within communities. This inspired him to start papermaking workshops where people could bring in articles of clothing with personal significance attached to them.

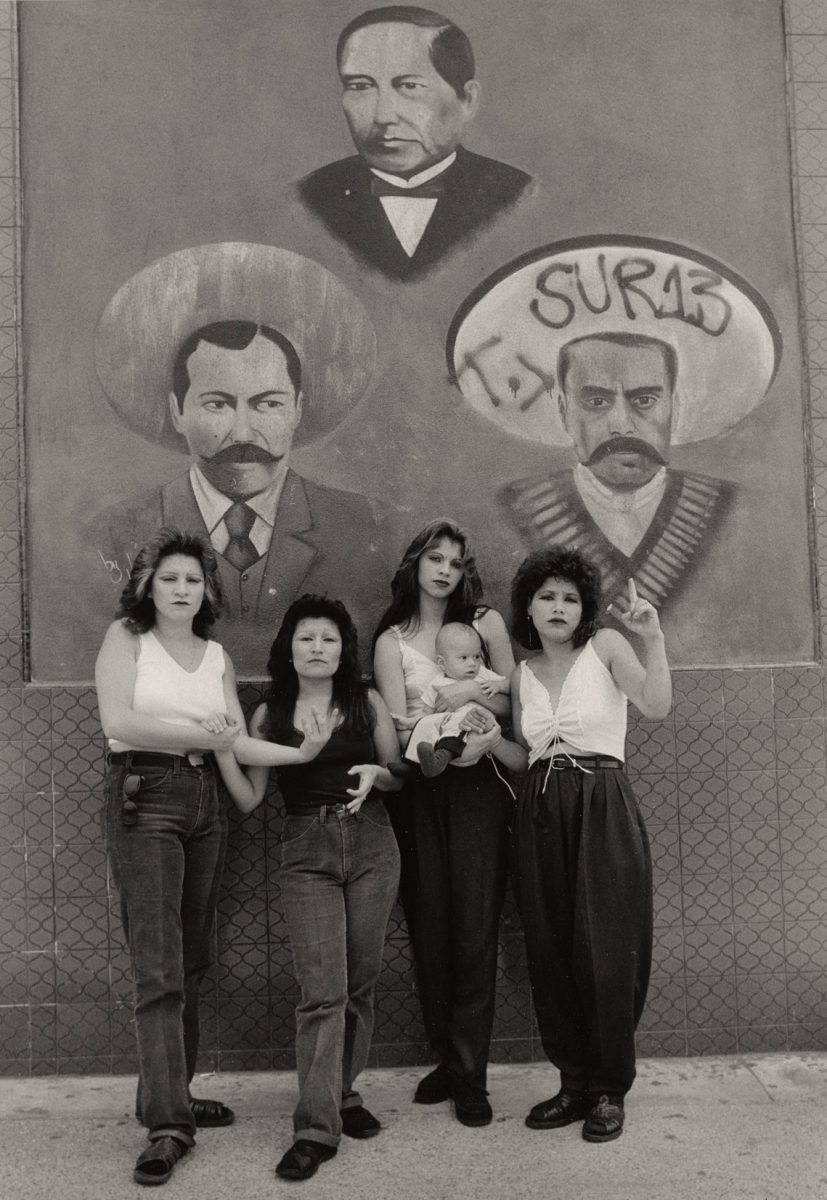

“People bring in their uniforms, they cut them up, and they share their experiences that are, more often than not, very traumatic,” Matott said. “I realized that when people were cutting up the uniforms, there was an emotional letting, a catharsis.”

Becoming more aware of the emotional impact that papermaking could have on individuals, Matott wanted to make sure that they were practicing the art in a way that was not harmful. This led to the creation of Peace Paper Project, a collaboration between Matott and Gretchen Miller, a licensed art therapist and certified trauma practitioner. The pair mainly hosted workshops at Veterans Affairs hospitals, working with veterans to heal their trauma through art.

“The main goal of Peace Paper Project is to use the practices of papermaking to bring people together and to address serious issues of violence, war, and terrorism,” Matott said. “We bring communities together to embark on a road of healing and recovery so that we can build a better society. What we’re stepping into is trying to disrupt transgenerational trauma. We’re doing that by using these workshops as a way for individuals to bring in something that they associate with their trauma and then transform it, giving it a space to exist so that it doesn’t get passed on.”

During his journey of creating this project, Matott went to the University of Illinois and met Valerie Hotchkiss, Azariah S. Root director of libraries and professor of English and Book Studies. The University of Illinois, with a long history of being accessible to veterans, became the archive for the ideas and examples of work that Matott was doing with veterans.

“I found it such an interesting project,” Hotchkiss said. “Some of [the veterans] gave their pieces to my former library in Illinois, and it was so interesting to read them. We also had a nice collection of poetry from the Vietnam War soldiers, and there was such similarity [in their pieces]. It was like they were timeless in their sorrows, worries, and epiphanies that they had as soldiers, even in their poetry.”

For Aimee Lee, OC ’99, papermaking is a way of connecting with heritage. Lee practices the art of making Korean paper, or hanji, and transforming it into more complex works such as artists’ books, sculptures, garments, and installations. Unlike Matott’s method of making paper from clothes, hanji is made from the inner bark of mulberry trees. Lee has been teaching papermaking and book art during Winter Term since 2014, where she guides her students through the entire process of creating hanji.

“Papermaking was done by the lowest classes of people, from peasants to prisoners,” Lee said. “The product itself was used by high class people like artists and government officials. It was a way for me to look at the inequities in the hierarchies of society. Once [my Korean diaspora students] learn to make hanji, they say that they feel so much more Korean. It roots you in a labor that has been done for almost 2,000 years. What I want [my students] to get out of it is more confidence in their ability to make things with their actual hands and to do things that have been done for a very long time.”

Matott is collaborating with the Bike Co-op for Saturday’s demonstration, where students will be able to use a bicycle to power the Hollander beater that will grind up clothing into pulp to make paper. He will bring material such as military uniforms from his travels, and students will be able to print designs onto paper and create a unique piece of art to take home.

“I’m hoping to introduce to students this idea of using papermaking as a form of peace and reconciliation,” Matott said. “This is part of a larger movement of papermaking as a form of art therapy and socially engaged art practice.”