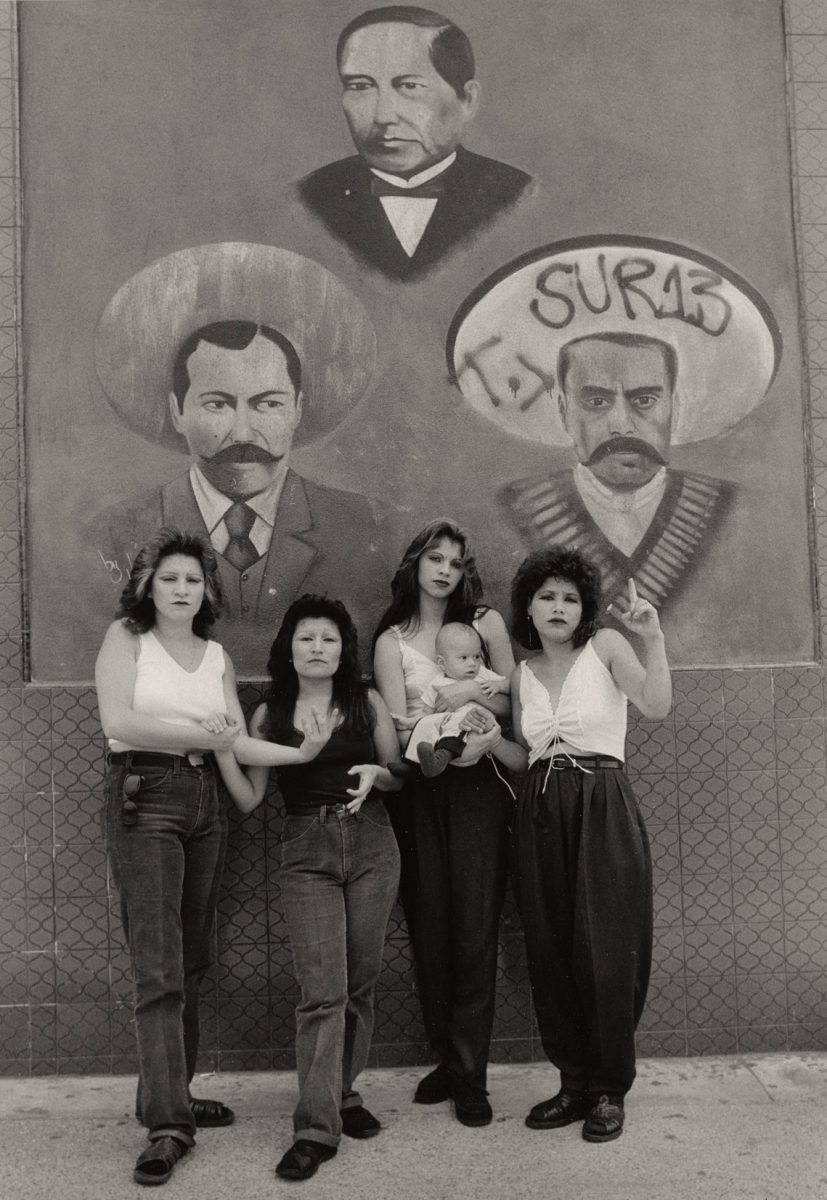

The Cleveland Museum of Art exhibit “Picturing the Border” showcases photographs of the U.S.–Mexico borderlands from the 1970s to the present. The photographed subjects range from black-and-white portraits to brightly colored political demonstrations. These humanizing images counter often derogatory immigrant narratives that circulate in U.S. mass media. The Cleveland Museum of Art exhibit asks the question: What truly defines citizenship, family, nationality, and borders?

“Picturing the Border” opened July 21 and will close Jan. 5. Although the CMA is a 45-minute drive from Oberlin, the exhibit has sparked much dialogue within the community. On Wednesday, CMA Curator of Modern Art Nadiah Rivera Fellah, OC ’06, conducted a lecture in Hallock Auditorium on “Picturing the Border” that was attended by many students. College fourth-year Niovi Rahme viewed the exhibit in person Nov. 2 and shared her feelings about the artwork.

“It was really beautiful, with wonderful selections of different, lesser known photographers that are from in and around the border,” Rahme said. “There’s a beautiful video of someone putting seesaws through the border wall. They were only allowed to keep them up for 20 minutes before the border patrol made them take them down. But kids were able to go on the seesaws from either side of the border and some adults were gathering around and playing. It was a beautiful example of how borders are just walls.”

Visiting Assistant Professor of Hispanic Studies Yorki J. Encalada Egúsquiza explained the nuance of what the U.S.–Mexico border represents.

“The border is presented as a space of death, because we know people die when they’re trying to cross the border,” Encalada said. “But also, for some people, it could be a space of hope. By crossing the border, they hope to make all these dreams that they want, economic stability or freedom. It could also be a space of cultural exchange.”

Professor of History and Comparative American Studies Pablo Mitchell, who researches and teaches about the U.S.–Mexico borderlands, offered his insight into the use of photographs in “Picturing the Border.”

“I tend to use photographs as historical documents,” Mitchell said. “I use those documents for information about the lives of ordinary Mexicans. While there tends to be a homogenization of this group, I think art can offer us a sense of the different perspectives and approaches that folks have.”

Intimate moments captured by a camera are often among the most revealing. Ada Trillo’s 2020 digital print, “Sleeping by the River, Tecun-Uman Guatemala” is one of many photographs in “Picturing the Border” that gives viewers a glimpse into lives often erased or ignored. The image pictures a naked child sleeping on a pile of clothing on the banks of the Suchiate River. The scene is peaceful but evokes a sense of weariness. The child looks comfortable in his makeshift bed, but the clothes strung between trees and litter covering the grass indicate the difficult journey of asylum seekers.

Encalada expressed excitement about the increasing accessibility of art.

“It’s very easy for artists to create something, then just post and share it with everybody,” he said. “That’s the beauty of photography; these kinds of artists are so easy to access, and it’s not expensive. In the future, I want to see more and more of this.”

Mitchell explained how to combat homogenizing narratives of marginalized groups that often circulate in U.S. media.

“What we do at colleges is we make things more complicated,” he said. “We ask questions, like ‘Do all Mexican immigrants have a certain political perspective?’ And not all do. We try to ask deeper questions about the communities that we care about and listen to as many different perspectives from within those communities. That offers us a way to counter some of those broader, shallow views of communities.”

Encalada echoed similar feelings toward harmful, anti-immigrant narratives.

“When I study stereotypes, it’s very common to talk about immigrants as invaders or people who bring diseases,” he said. “Stay away from those narratives. Look at everything with a critical eye. Please stay away from dehumanizing narratives, because that’s the worst that we can do.”

Rahme offered insight into the arbitrariness of borders, reflecting the themes raised by “Picturing the Border.”

“Borders are just randomly drawn lines that cross groups of people,” she said. “People don’t cross the border.”

Encalada encouraged Oberlin students to take action to combat stereotyping. He proposed activism beyond simply voting.

“Voting is your civil duty, but you can also go out and try to get involved,” Encalada said. “For example, there is this group of students, Allies for Undocumented Inclusion,” he said. “This week, they are doing all these events. Try to get involved in those activities. Try to support the community. That’s very important.”