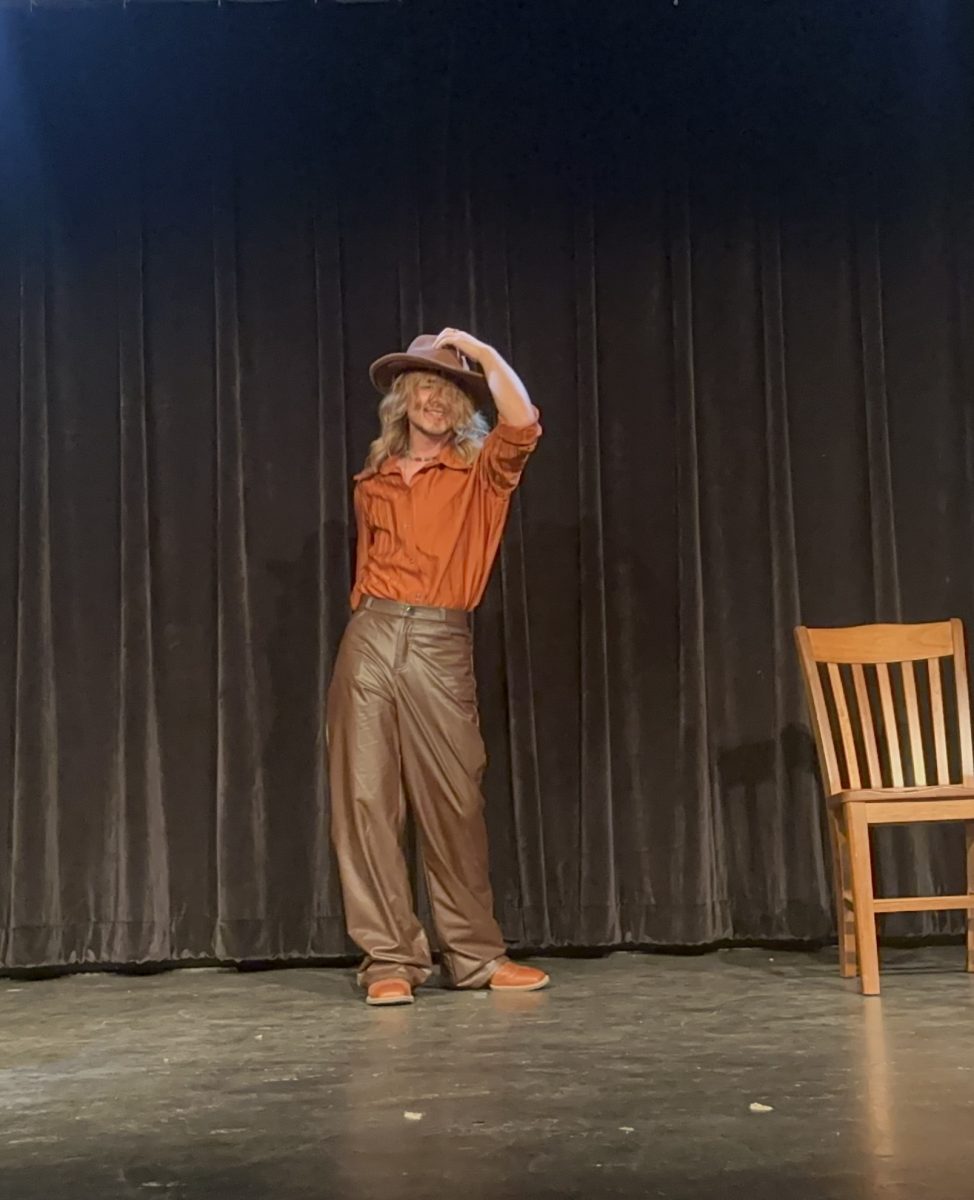

Prestø is a world-renowned dancer, choreographer, and founder of the Talawa Technique and the Tanbaka Ensemble. Every piece of his work focuses on decolonizing dance and embodying one’s true self and body. He developed and researched the aesthetics and technical elements of African-rooted dancing, and has made great contributions to the field of Africognosomatics and Africana Performance Studies. He is currently a visiting assistant professor at Oberlin.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

What is the most important part of dance to you? What aspect of this art form speaks to you the most?

In order to dance well, you must accept and master yourself. So for me, that’s the part. Dance is a way to check in with but also move with yourself. In order to feel what you’re doing, you have to move with yourself, in a sense. And I’m saying that because it’s possible to move not with yourself … it’s possible to be less embodied or to be disconnected from yourself. But in order to really dance— mind, body, spirit, heart, feeling— all of it has to come together and be present and kind of be cohesive … dancing is the most joyful coexistence I can have with myself, to put it that way.

What inspires you when you choreograph or when you create new terms or techniques?

I try to choreograph people into existence. So, so often, many of us exist in a kind of a police state, or reduced state. We have to make ourselves smaller, make ourselves less. So I try to choreograph in a way that amplifies and allows us to, in different ways, spread out and allows us to exist. So, I’m inspired by body language, by people especially, and sometimes also when I’ve seen a really interesting body language, when I’m thinking that, “Oh, I’ve seen this body language in other people, but suppressed,” and that makes me often want to put that on stage, but in a large way, to make it part of the norm. And kind of like, also imagine, “Okay, if that person wasn’t self conscious, how would they move,” for example. So, unapologetic.

What led you to develop your Talawa Technique? What was your creative process like?

It was more of a nerdy process than a creative one, maybe, but there’s creativity in it … there was research, due diligence, problem solving. It is a very complex system of mapping the body and mapping dances that are rooted in African heritage to not treat it as aesthetics, but also treat it as mechanics. So, what are the mechanical or technical reasons for your arms to be here, your feet to be there? So very often it’s described as aesthetics, and there’s a difference between aesthetics and technique, but they also have to coexist, because if you don’t have technique, you won’t be able to get aesthetics.

And not all aesthetics are for technical reasons, so it’s kind of getting down to what is technical and what is aesthetical, so that you rebuild it in a way. And because of colonialism, because of racism, because of many things, African-rooted dancing is seldom talked about as technical; because if it’s technical, it has to be intelligent, and if it’s intelligent, then it’s culture and it’s ethics and it’s all other things. And because the black body is supposed to just be reactionary, it couldn’t possibly be intelligent if it comes from that body, right?

And that’s a problem, so people don’t call hip hop technical. If you watch So You Think You Can Dance, the hip hop dancers are told they don’t have technique, but if a ballet dancer is trying to dance hip hop, they say, “Oh, that was a good job on doing this very difficult, grounded technique.” So suddenly it’s technical. It’s a politics in who are allowed to and who are not allowed to have technique, and who’s allowed to have an intelligent body and who’s not … so a lot of it has also been navigating that, but it’s been a journey taking the African vocabulary and African diaspora vocabulary seriously. The techniques takes it seriously, and then what’s the consequence of taking that seriously? What does that mean for training? What does that mean for virtuosity? What does that mean for standards?

And then developing a system that will allow you to reach the height of our standards; the dancers in my company are elite dancers, and several of them are known around the world for being among the best in the world at what they do. And that’s not that that’s the only point. I believe that dance should be enjoyed for the people who just want to move for the joy of moving, right? I also believe that you should, if you should want to. My job as an educator is to give you a foundation in which you can build on, and if you want to build a cottage, build a cottage, and if you want to build a skyscraper, you should also be allowed to build a skyscraper. And that’s how I try to teach. I try to teach a foundation that people can enter at many different levels, but it doesn’t hinder how far you can go.

What is your advice to dancers who want to practice embracing their bodies and backgrounds in the concept of “dancing well,” but they might not know where to start, or they might be a little worried or uncomfortable, or they have all this past training that they have to undo, or something like that?

Really, embrace your own body language. So I would say, almost bring it back to language. Write a sentence, write something you want to say. Then figure out how to have your body say it instead of your voice. And then just create some movement and some phrases around that, that you do to all kinds of music. So switch like, make a random playlist and then try to communicate that same thing regardless of which song comes on. For example, just to free yourself from your ideas of what it’s supposed to be, right? So to allow yourself to be, first; kind of unapologetically, and then you could almost say, like the music just becomes, I would almost say, like a language. I speak multiple languages, and I speak them differently, meaning, some I speak with a deeper voice. Some I speak with a lighter voice. Some, my voice is more feminine, more masculine, all those kind of things. So, some of the qualities of my voice changes according to which language I’m speaking, but I don’t change. I don’t stop being me just because I’m talking a different language. So very often people, for example, who do ballet and those things, they stop being themselves in order to do ballet. And I think that’s where we have to get to, where you can be yourself regardless of which language you’re talking.