This Is Our Youth: Little Theater Mounts Cynical Portrait of College Student Malaise

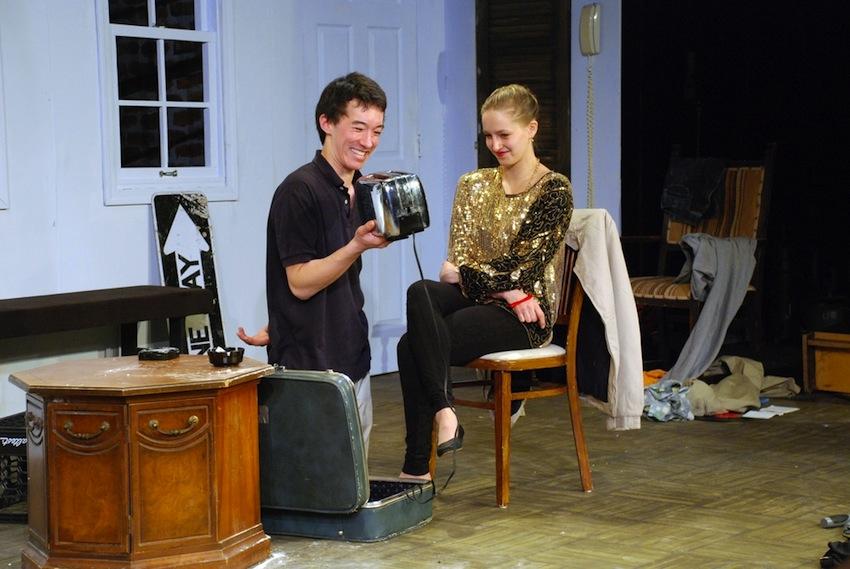

College senior Josh Silver shows off his vintage action figure collection to College sophomore Samantha Bergman in Kenneth Lonergan’s brutally comic vision of sex, drugs and toaster ovens amongst Manhattan’s privileged youth.

March 11, 2011

Kenneth Lonergan’s This Is Our Youth is a serious play about three characters whose lives are serious jokes. The synopsis reads like a tale on the brink of tragedy: Set on Manhattan’s Upper West Side, Youth tells the story of the privileged adolescent boy Warren (played by College senior Josh Silver), who goes into hiding after stealing $15,000 from his father. The reckless, feckless Warren proceeds to spend the money frivolously, a misstep that he remedies by selling the cocaine that is later implicated in an acquaintance’s death.

The logic of dramatic convention would dictate that a desperate, hapless character like Warren must be on the brink of a tragedy. The beauty of This Is Our Youth, however, is that he isn’t.

Danger, fragility and a constant awareness of mortality are the notions that seem to keep many if not most people active. Yet try as they might, the characters in Youth (brought to life with aplomb by director and College senior Philip Waller) are unable to fully grasp any of these concepts. Like most tragic heroes, Lonergan’s spoiled and sluggish youth suffer from one fatal flaw: Their inability to agitate their invincible upbringings will eventually lead to their downfall. However, Youth differs from tragedy in the sense that our heroes’ epic “downfalls” are essentially slight bumps on otherwise smooth terrain; At the end of the road, the characters are all right, and the dangers they encounter along the way are somewhat illusory.

As Warren and Warren’s hot, charismatic friend Dennis, Silver and College senior Tip Scarry did an inimitable job of bouncing from their lethargic positions on Dennis’s old mattress to hyperactively shooting around the room like pinballs (Warren) and torpedoes (Dennis). Their volatility illustrated that these emotions are just as shakable as a game of make-believe, and in both of these characters, we saw children living in skins that have outgrown them.

Despite a couple of moments of anticipated theatricality, Scarry’s Dennis was one of the strongest performances in recent Oberlin memory. His shocking vocal and physical range, goliath presence and carelessness with personal space all provided the audience with insight into the inner workings of his character. One monologue in which Dennis articulates his desire to one day become a filmmaker (despite never having handled a camera) was delivered with stirring, desperate bravado. Boasting of his proclivities toward filmmaking, Scarry made it clear to the audience that Dennis, like a child bragging about one day becoming a fireman, would never realize these aspirations.

Indeed, Scarry was so comfortable with his body that he seemed unapologetically at the mercy of his bodily functions and needs, blowing his nose with repellent fervor, crying exaggeratedly, roughhousing and throwing and humping his best friend — all with his hands thrust down his pants. Silver was also quite excellent, imbuing Warren with a neurotic tremor and an uncertain physicality that perfectly contrasted Dennis’s authoritative demeanor.

Finally, College sophomore Samantha Bergman found great depth in the role of Warren’s ambivalent love interest Jessica Goldman, a fledgling fashionista with a penchant for gold sequins and a subdued, uncertain personality that was at odds with her flashy garb. Bergman’s chemistry with Silver was startlingly natural, and though his character’s awkwardness may have led some to question his sex appeal, I understood why he got the girl in the same way I understood why Woody got Mia (or Diane. Or, um, Soon Yi).

Overall, the actors reached their performative peak in their interactions with objects. Thanks in part to a meticulously squalid set design by multitasker Silver, props that first seemed randomly strewn about the room were gradually revealed as carrying emotional weight for the characters. Toasters, action figures and baseball caps evoked vulnerability and vitality in the characters, and some objects provoked certain recurring facial expressions to superb effect. For instance, Silver had a toaster face and a hat face, while Scarry had a phone face, a porn face and a joint face. I’m gonna miss all those punims.

Phone faces and porn punims aside, the dramatic conventions of tragedy are reversed by the end ofYouth, as the audience perceives that neither Warren nor Dennis turn out to be in any kind of real or mortal danger. They are able to rile themselves up enough to believe that their sordid circumstances are dire, but Warren’s closing line — “I guess I’ll just go home” — suggests that they can return to suckling the teat of their privileged childhoods once they’re ready for the simulation of real-life danger to end.

It is not the illusion of danger created by the stolen money and the spiteful father that provide the climax of this play. The climax is felt, rather, through the intensification of the characters’ denial regarding the pointlessness of their existence. What we’re left with is not tragedy, but a fascinating failure to overcome the boredom of excessive privilege.