“Imprinted Legacies” Takes on Family History

College Senior Claire Stepherson utilized innovative materials like molasses, hair pomades and shoe polish.

April 29, 2011

“They used to call me chop-suey in Hawaii whenever I went there with my family,” said College senior Claire Stepherson, explaining the first part of her artist statement. “My skin would get really dark, and my hair would be really light.”

Hidden in the back room of the FAVA Gallery, students and faculty alike acclaimed Stepherson’s exploration of her identity with praise and awe. Her media of choice — molasses, hair pomades and shoe polish— were particularly impressive and related back to her family.

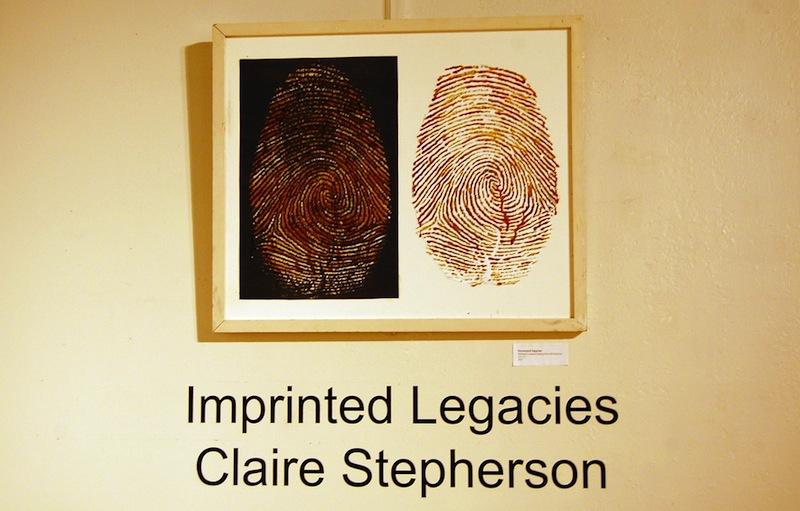

Stepherson spoke of how her family used to eat molasses a lot when she was a child, and how she had bought the hair pomades her father used to use. The fact that her father always used to polish his shoes also made its way into her art in the form of thumbprints made with shoe polish.

Having interviewed multiple family members, Stepherson put up typewritten excerpts and narratives of her discoveries, deliberately keeping in the typos and run-on sentences that reinforced the sense of initial discovery she spoke of. She also added handwritten notes, afterthoughts and edits, making the exposition of her father’s story a little more intimate.

Of all the symbols used — roots, footprints and thumbprints — the last perfectly conveyed this exploration of self and history. A large thumbprint with an embryo in the center, made up of paper and molasses, was sold within the first 15 minutes of the show. A large cloth with molasses-imprinted footprints also played with the idea of identity — almost as though Stepherson wanted to leave her own mark through her discovery of family history. She talked about how she would have liked to incorporate her mother into this narrative as well, and that she tried, but was not “quite there yet, in terms of [their] relationship.”

The centerpiece was a giant, intricately cut paper figure of a woman, with the parts below the neck turning into complicated roots and her hair blending into branches. Though Stepherson expressed dissatisfaction with the piece, her audience begged to differ, and their words of praise echoed throughout the space.

The impressive array of works and unconventional materials made Stepherson’s show a success, one that begs for a sequel if only to see how she would interpret her relationships with other family members.