New Curator’s Exhibit Explores Artists’ Imagination

Courtesy of the Allen Memorial Art Museum

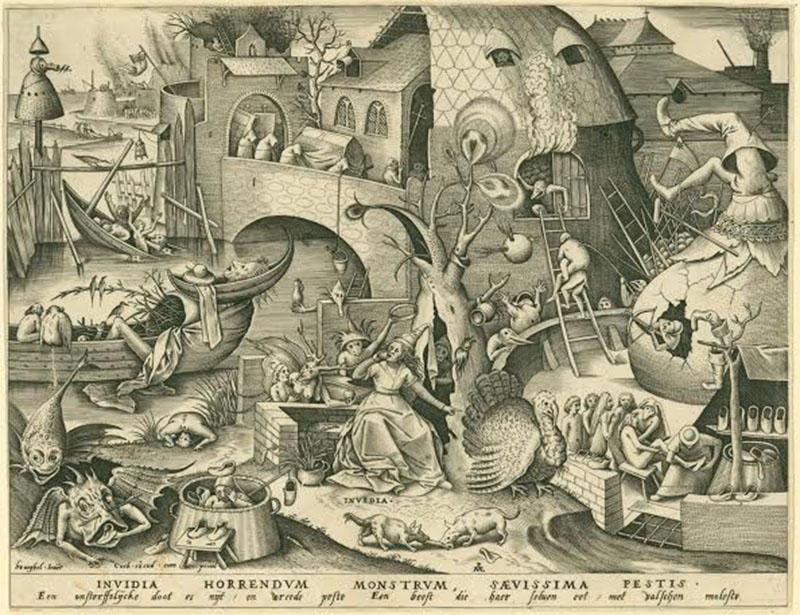

Invidia (Envy) Personified by Pieter van der Heyden and Pieter Bruegel the Elder is one of the prints featured at the Between Fact and Fantasy: The Artistic Imagination in Print exhibit. The collection, on display in the Ripin Print Gallery in the Allen, explores how artists visually interpret the world of the imagination.

February 14, 2014

Anyone who’s taken a drawing class has likely heard the instruction, “Draw what you see.” But how does one draw what one can’t see? As an exploration of this topic, the Allen Memorial Art Museum’s Curator of European and American Art Andaleeb Banta has put together a collection of prints that depict various elements of the fantastic titled Between Fact and Fantasy.

Banta joined the Allen this past July, after working at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., where she was the assistant curator of old master prints and drawings. Given her previous experience with the medium, it is fitting that her first AMAM exhibition is composed entirely of prints — which, in fact, make up more than half of the museum’s collection. The prints in the exhibition span over 500 years of art history, with works created as early as 1400 and as late as the 20th century.

The exhibition serves as a counterpoint to the museum’s focus on realism this academic year. While the entire John N. Stern Gallery has been devoted to an exhibition that surveys 19th and 20th century artists’ interpretations of what realism is, the upstairs Ripin Gallery is devoted to Banta’s exhibition.

In the 19th century, artists began largely to occupy themselves with representations of reality. Painters found themselves preoccupied with narratives that are located in fleeting moments: light falling on hay at sunset, or waves breaking on driftwood lining an empty coast. At the same time, fascination with the impossible continued. While realism searches for truth in the artistic representation or abstraction of life, the fantastical exhibition Banta has constructed allows for an examination of artists’ attempts to describe what they do not know or cannot see.

The exhibition is divided into five sections: “Fact and Fiction,” “Places Real and Reimagined,” “Gods and Heroes,” “Visions and Miracles,” and “The Artist’s Imagination.” In an interview with Banta, she said this decision was made in order “to give the viewer the chance to regard each artist in his own light, as opposed to making any argument about the evolution of the fantastic over time.” Looking at the prints in the gallery, it’s clear she achieved this goal; one might regard each artist in Banta’s exhibition as an auteur who used the fantastic in one way or another to tell a story or communicate an idea — deeply personalized, yet deeply contextual. Each print approaches the fantastic or imaginary as a tool for communicating a story, event or idea that pertains to a historical or cultural moment.

In the “Gods and Heroes” section of the exhibit, one might look at a scene of Saint John receiving the five books of the New Testament from God. While the story as described in the Bible calls to mind a range of possible images and interpretations, Albrecht Dürer’s depiction of the moment gives visual particularity to the abstract, mythical event. His vision is neither correct nor incorrect, but observing how he tackled this scene in a single image exposes certain truths about how humans deal with the unknowable.

Banta recommends taking in “The Artist’s Imagination” section from start to finish, which she says is “the catch-all for the exhibition.” In this section, each artist is acknowledged as the holder and master of the fantastic, and the subject matter is highly diverse. Acting as bookends, two interpretations of sin sit on each end of the north wall. One is a deranged reiteration of “Envy, from The Seven Deadly Sins” printed in the style of Hieronymous Bosch by Pieter Bruegel the Elder; the other is Edvard Munch’s “Sin,” a minimalist depiction of a nude woman who possesses a maddening gaze.

It is rare to find such diverse artwork in extremely close quarters. The sole limitation Banta placed on the exhibition was that it would be composed solely of reproducible media, which she thinks is an appropriate choice for images of the fantastic. “For mediums that are reproducible, the stakes are lower,” she said. “Many of the artists featured in the exhibit were producing within very strict political limitations. Prints were an exception to these limitations.” Walking through the hall of the Ripin Gallery, one is confronted with works of art produced with the greatest liberty possible by the artist, and, as such, images that subvert the boundaries of what we know and see.

This exhibition displays various ways the fantastic is used as a tool for describing what is beyond realism. After strolling through this exhibition for a while, you might find that the vocabulary with which you read an image has changed. Reality and imagination have been conflated ever so slightly. The exhibit, placed in the context of the pieces in the modern art galleries, describes various subtleties about how artists approach the immaterial world. “In curating this exhibition, I was interested in the balance between the sane and the insane,” said Banta. “I find that the most successful works of art find themselves right between the two.”