Research Conference Recognizes Minority STEM Students

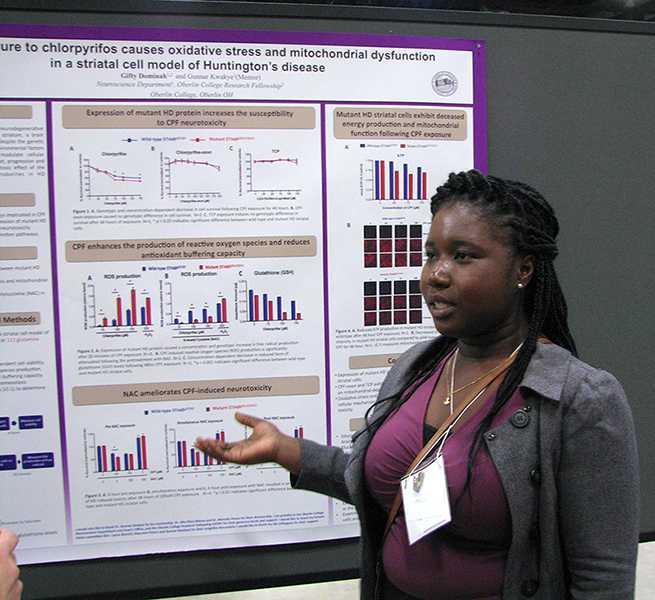

College senior Gifty Dominah presents her poster at the Annual Biomedi- cal Research Conference for Minority Students in San Antonio. Dominah was among seven Oberlin students and two faculty members to attend the conference last week.

November 21, 2014

Oberlin sent a team of seven students to the Annual Biomedical Research Conference for Minority Students in San Antonio last week. There, several students earned first place in their field for their posters.

College seniors Marisa Aikins, Hudson Bailey, Gifty Dominah, Michelle Johnson and Gabriel Moore and College juniors Anne Chege and Edmund Korley, along with two Oberlin faculty members, traveled to the conference last Wednesday to present their research at one of the largest professional conferences for minority students in STEM fields in the country.

At the conference, students were judged on their oral presentations or presentations of a poster.

The judging for the competition is considered highly rigorous. Of the approximately 1,700 undergraduate students in attendance, only 180 received accolades for their presentation.

According to Director of the Multicultural Resource Center and Associate Dean of Academic Diversity Alison Williams, who judged a number of presentations herself, the rubric is “very rigid.”

“You’re looking at how well the student understands the problem that they’re trying to study, how they put it into a bigger context, how well they understand the methods they applied to the problem, how well they understand the data, interpret the data, draw conclusions,” Williams said. “You look at the overall presentation quality in terms of slides, or if it’s a poster, the quality of images of the poster, the clarity of their presentation in general. It’s an overall assessment of the quality of the science as well as the presentation.”

At the conference, several Oberlin students received recognition. Korley won for best oral neuroscience presentation, and Aikins and Chege won best physics and neuroscience posters respectively.

Korley said the conference helped him put his career goals in perspective.

“It was nice, but I got a lot more from [the experience] than that award,” Korley said. “Part of that is that I always thought I would go into a career as a physician, and doing research was a step towards that. But going to that conference and seeing all that amazing research going on showed me that research is a career in itself, so that’s got me really excited about research and [has caused me] to re-evaluate my career goals.”

Korley wasn’t the only participant who benefited from the career-oriented nature of the conference. For Aikins, one of the most beneficial aspects of the conference was the opportunity it offered participants to develop professional connections.

“[It] was filled with graduate school representatives, which allowed us to explore various graduate programs in our fields,” said Aikins. “It was especially useful to those of us who are applying to graduate school now.”

Aikins added that graduate school recruiters approached many of the students because of their presentations.

“I would suggest any minority in the biomedical sciences to attend,” she said.

Many of the presentations

from Oberlin addressed different questions and topics in neuroscience. Korley, Chege and Dominah study different aspects of Huntington’s disease and the brain: Korley focused on cadmium interactions, Chege studied the effects of the pesticides deildrin and lindane, and Dominah looked at the effects of chlorpyrifos, another pesticide.

Johnson studies the transcriptional control of the first known mammalian brain-specific tRNA, and Bailey studies how the brain integrates audio and visual signals based on the signal.

In microbiology, Moore works on identifying compounds that could reduce the virulence of gram-positive bacteria. Aikins, who specializes in physics, tracked fluorescently tagged mucus proteins to identity a mucus-based immunity mechanism present in the body.

According to Vinces, the College received a personal invitation to the conference last year.

“They thought it was really important for Oberlin to be there,” Vinces said. “We haven’t had a presence at this conference, even though Oberlin’s history would suggest that we would.” With last year’s invitation, the conference extended an offer to fund students’ travel to San Antonio. This year, however, the team did not initially receive funding directly from the conference itself — a development that proved problematic in the early stages of its travel plans.

However, the group was able to receive funding through other means — such as Vinces’s and Williams’s offers to judge presentations in exchange for funding from the conference. Edmund and Bailey won travel awards from the conference, and the other students turned to their departments for funding, obtaining awards from the Oberlin Chemistry and Physics departments. Moore was able to obtain funding from his research lab at Tufts University, and all the students received substantial additional funding from the Office of the Dean of the College and the MRC.

“For the future, it’s going to be an issue if we can sustain to take a team, because it costs a lot,” said Vinces. “So that’s something for future discussion — what’s a sustainable model regarding student participation and this conference and other conferences.” Vinces and Williams have discussed crowdfunding and potentially reaching out to alumni as alternative sources of funding.

For both administrators, however, there are more pervasive issues than a potential lack of funding, namely the lack of support for minority students in the STEM field. According to Vinces, while the College sends a number of students to Ph.D. programs, minority students are often underrepresented in these programs. This trend is particularly pronounced among first-generation students.

“Given the history of Oberlin, yes, we’re leaders in science, and we have this history of accessibility to higher education, but they could be better coupled today,” said Vinces. “We could do better.”

According to Williams, the College loses minority students in STEM fields between the introductory and upper-level courses.

“Our hardest task right now is getting students to come in through the intro courses and persist into the upper-level courses,” said Williams. “Once the students get through and into the upper-level courses and into a lab, they’re very well supported, but getting them to that point is where we sometimes reach stumbling blocks.”

However, Vinces, Williams and other administrators are currently working towards a solution.

“There’s no easy solution to this, so we’re trying to come at the problem from lots of different angles,” said Vinces. “We’re doing faculty workshops to raise awareness and to get departments to talk to each other. Some departments are doing better than others, and it’s great if they talk to each other to see what each department is doing, as well as [doing] more grassroots work with students.”