Performance Art Grapples with Girlhood, Grieving

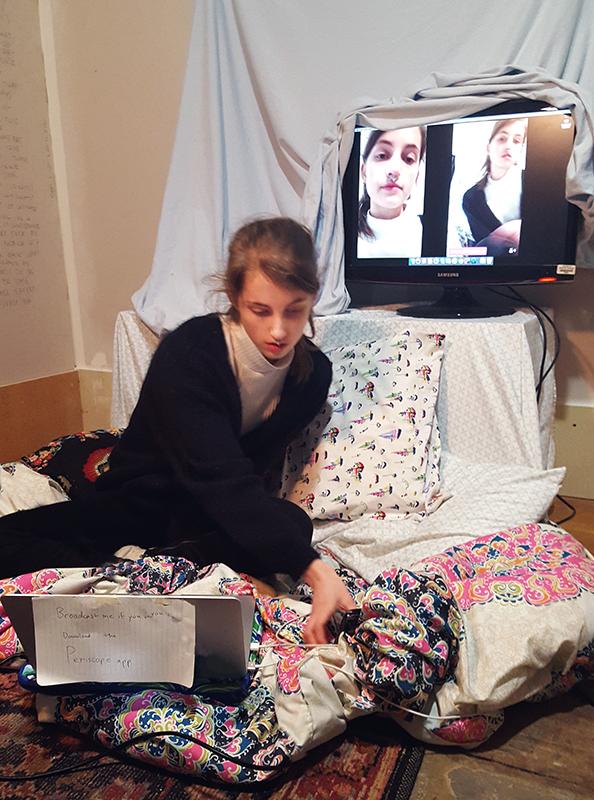

College sophomore Elizabeth Grooms creates a live stream of herself as part of the Performance Art & Technology Winter Term class taught by Art Department Technology Coordinator Francis Wilson. Students learned about the history of and the technology used in performance art.

February 5, 2016

For her final performance in the Winter Term Performance Art & Technology class, College sophomore Elizabeth Grooms filmed herself with Periscope, an app that allows users to livestream anything and viewers to leave comments on the video. She performed her installation alongside classmates at Storage art gallery on Jan. 28. Grooms’ project focused on how girls and women view themselves through technology. “I was filming a video of myself, and then people were commenting, but I wasn’t saying anything,” she said. “Then I was reading the comments in another video that was also being livestreamed, and it was just this cycle.”

The Winter Term class, offered for the first time this year by Art Department Technology Coordinator Francis Wilson, OC ’12, provided students with a historical overview of performance art and gave them hands-on experience in creating it. Some of the first creators of performance art in the ’60s emerged from movements like Dadaism, an anti-establishment art movement that posited that anything can be art.

“To define [performance art] is really difficult because a lot of the point of the movement in the ’60s and ’70s was that these are taking things out of your daily life and just doing them, but doing them in a gallery or doing them as a performance,” said College sophomore Han Taub. “There’s one group that had one piece called ‘Making a Salad.’ So they stood in the gallery and made a huge salad, and that was the piece.”

Historical context provided in the class helped Grooms conceptualize her final installation. She said she drew her vision from famous performance artist Marina Abramovic. “[Abramovic] had a piece where there was a table with a bunch of objects on it,” Grooms said. “She just stood there for six hours and let people do whatever they wanted to her, which I thought was really cool and inspiring.”

Wilson explained that from the ’60s to the present, the human body has taken center stage in many performance pieces. “The ’60s was a time when … performers were using the body as the main medium of performing,” she said. “The body’s role in performance has been something that’s been talked about and been a consistent conversation throughout performance art since then.”

College junior Fiona Hoffer’s final performance, which was about grieving and healing after her mother’s death, presented the theme of using the human body as a creative agent. Her piece included a live video that tracked Hoffer’s repetitive tumbling movements in a white outline alongside text that read, “My mother died like an exploding star. Today is 812.” While tumbling, Hoffer counted to 812, the number of days it had been since her mother had passed away.

Hoffer said the creative experience was taxing, but ultimately rewarding. “It was very physically exhausting and mentally exhausting, but there’s also this meditative quality to it,” she said. “So, for me, [part of it was] just pushing myself to do it when I had never done it before, because I’m not going to practice doing that 812 times. … I find it really useful to address personal trauma through creative things, because it allows me to work with them in a way that’s slightly removed, because it’s going through a creative lens. So I’m still doing the work that I need to do emotionally, but it’s still way more fulfilling than addressing those issues any other ways, because I get to make something that I love.”

In addition to learning about the historical context of performance art, Wilson also introduced students to technology as a resource. The class worked with Isadora, a program used to create live videos that allows one to change how a video is reacting, as well as Arduino microcontrollers. Wilson said that Arduino technology is easy for beginners to use, since students don’t need to know how to program. “It really allows artists to experiment with DIY technology,” she said. “I had several Arduino boards with some premade sensors that either reacted to light or to heartbeat, or to if it bends a certain way as a way of introducing how we can use the space around us or our bodies.”

Throughout the class, students gained hands-on experience by creating short pieces through video or live performance that culminated in the final showcase at Storage. One assignment was to create some sort of public disruption and document it. For this assignment, Taub sat on the floor of an Allen Memorial Art Museum gallery and colored in a Star Wars coloring book with markers while recording the experience. Another short piece they created allowed them to explore their own identity. “I played a1950s anti-gay PSA, and I sat on the floor and covered myself in finger paint,” they said. “It was an interesting experience for me as a performer, since it was a really vulnerable space to be i n .”

Taub said they appreciated the class, since it is one of few opportunities on campus that focuses on both learning about and creating performance art. “Performance art is something that there’s not a whole lot of stages to do it unless you decide to do it yourself,” they said. “Painting classes will have showcases and photography classes will have galleries, but there’s not really a place here to do performance art, so it was a nice experience to have in a classroom.”

Wilson said performance art remains approachable to many people, since it’s such a wide-ranging medium. “I think it’s something that people from any kind of creative background can engage in, because there’s actually an infinite number of ways that one can perform or be a performer,” she said. “I think everybody has some way in which to do something in front of an audience that feels natural and comfortable while still being challenging to them.”