On the Record: Jennifer Hoock, OC ’83, Cat in the Cream Founder

Photo courtesy of Jennifer Hoock

Jennifer Hoock, MD MPH, took over the Cat in the Cream with two friends and moved the venue to its current home next to the bowling alley.

May 6, 2016

Jennifer Hoock, OC ’83, aided in the re-establishment of the Cat in the Cream with roommates Charissa Smith, OC ’82, and Cheryl Serrone, OC ’83. She graduated from the Duke University School of Medicine and earned her MPH at the University of Washington. In addition to being associate director at Group Health Family Medicine Residency in Seattle, she is a founding member and director of development at Guatemala Village Health, a nonprofit organization that promotes education, better health care and economic development in remote Guatemalan villages. The Review contacted Hoock for a phone interview to talk about her experience with the Cat in the Cream as well as the influence her time at Oberlin has had on her work.

How did the Cat in the Cream begin?

We actually didn’t start the Cat in the Cream. It was actually originally in the basement of Asia House. … It was a very informal gathering [place], mostly around folk music and maybe a little bit of poetry reading. I don’t think most people even knew it existed because of where it was located, and from wherever it had started, it was winding down and about to close.

Somehow, we had gone there for some event and found that out … so we started hunting around on campus, and [we found] this room next to the bowling alley. It was full of stuff when we found it, and we were like, “Can we clean this room out?” … We had to find a place for all the stuff, and in the process, we discovered a tandem bicycle with banana handlebars, and that became sort of our “Cat in the Cream mobile.” We used it to carry flour and sugar and what have you across the street, because we actually did all our own baking. We would get the flour and sugar through the Rathskellar, and then we would truck it across the street by carrying it on our bike.

Is that where the famous cookies started?

Yes, that is where the cookies started. And at that time, Jazz was not a part of the Conservatory. My roommate Charissa played in the Conservatory — she was a French Horn [student]. And then my other roommate Cheryl, we all were jazz aficionados, and the jazz folks were like, “Oh, we need a place to play.” … We were actually probably more jazz than folk music, even, as we got started. We never had anything that formal — it was all just chairs and tables that we had scavenged.

We didn’t really have a stage, and we got the Conservatory to donate an old piano. … We had a lot of fun with it. … I was blown away to go inside [recently] and see how remodeled it had been. … It’s amazing that it stayed there.

What was your vision of what the Cat would be like going forward?

I don’t think we really had that sort of vision. I think we did ensure that we passed it on to folks who we thought would keep it going, but it wasn’t like we had a sustainability plan. It was an on-campus student organization, so it had that structure in terms of continuing, but other than that … I don’t think we had any clear, “Let’s make sure this keeps going” kind of thing. I think it was more the social experience of sharing something we liked with people that we got to know.

Do you think student ownership was an important part of what made the Cat in the Cream successful?

Oh, yeah. I think it was a great opportunity because we had the ability, unlike many of the other things on campus, to decide what we wanted it to be. It would be interesting to find out how far back the Cat went as a folk club, but I think that during the ’60s, that [scene] was much more prominent. I came in 1979, and jazz was much more a part of that age group. Because you know, the Vietnam War was over and that sort of thing, and that was the winding-down, perhaps.

But I guess we hoped it would continue to be a place for students who identified with performance. … It was a place where — whenever people had something they wanted to perform that they couldn’t find a place for — it was a nice venue for that. But it was under our control, and I think that made it much more accessible. If you played in the Conservatory or what have you, you had to have a very polished, professional performance, and this was much more informal. I think it allowed people who weren’t as advanced or as sure of themselves to participate.

What was a day at the Cat in the Cream like?

We’d go in, and we had an old coffee percolator, and we’d put apple cider in it to heat it up. And we had the cookies that we had baked — I don’t know how we had time to do all this — but that we had baked the night before. It was very much a community activity. There were usually four people there running the place. … We clearly sold drinks and sold cookies, so I guess that was the revenue that ran the place, but I don’t remember much about that part of it.

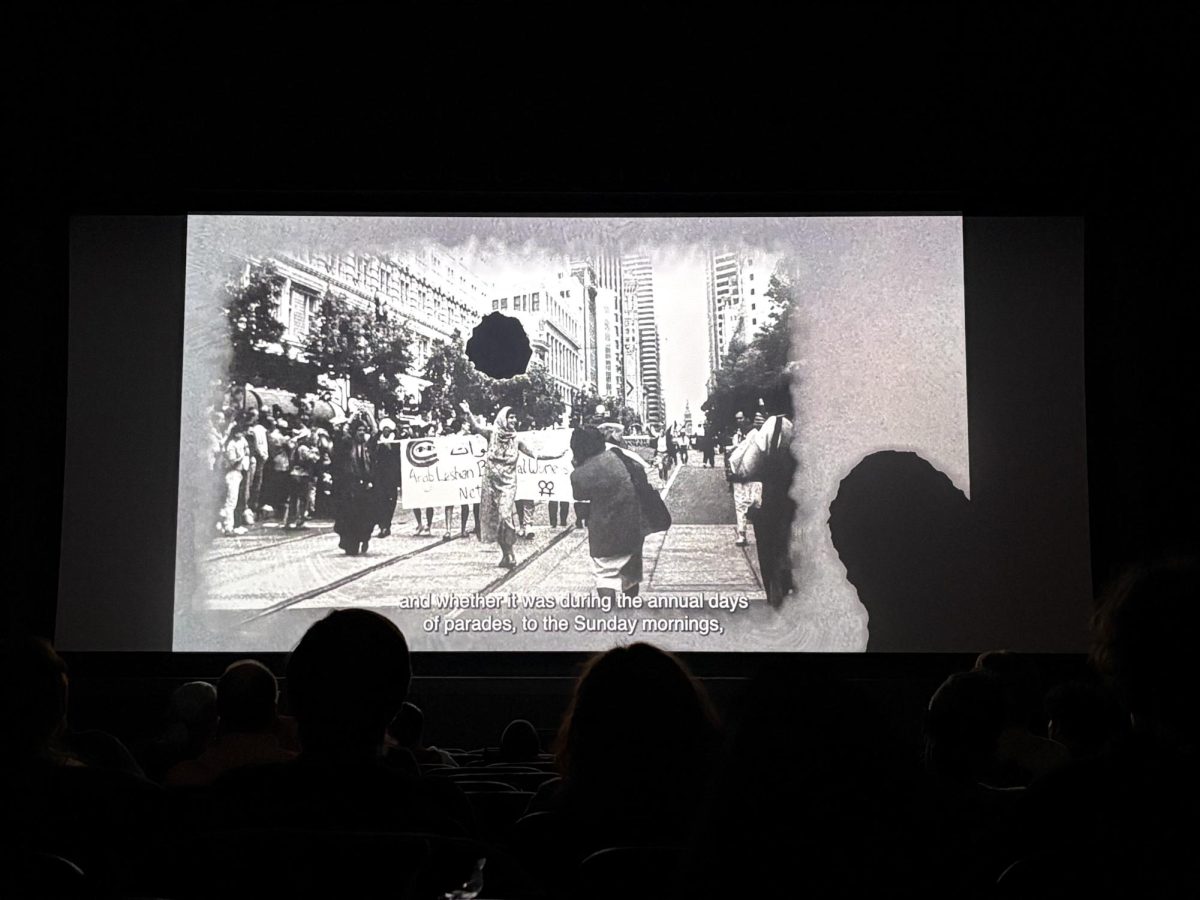

And people would come in. It was very much sort of a coffeehouse. Whoever was performing was performing, and people would sit around watching or chatting or what have you. I think, by and large, it was more come-to-watch-theperformance than just hanging out and drinking coffee, but there were certainly a lot of conversations that went on there. We would often stay, it seems, very late at night, just hanging out and then closing the place down. It was an alternative — I mean, at that time, Oberlin was a dry town, so there wasn’t a whole lot of drinking going on anyway, but the [Rathskeller] and the ’Sco were loud and boisterous and active, and this was a lower-key place to hang out and just be with people.

What was your experience with Oberlin as a whole?

I had a wonderful time at Oberlin. I grew up in Gary, IN, and I had really never been much of anywhere besides that. I knew it was a pretty big world out there, and I came to Oberlin to find it. I had a blast trying out all sorts of things, so it was a very fundamental experience for me. I’ve always remained close to it, although unlike a lot of people I knew, I didn’t have other family members who were there.

I was an incognito pre-med student. [It was] very much not a good idea to be pre-med at Oberlin at the time. I studied Psychology and Biology, and I was trying to decide between whether I wanted to be a clinical psychologist or go to med school or do research. I really had the flexibility to try out all those things. I loved the fact that at Oberlin you could wear whatever hat you wanted at whatever point you wanted, and I went between a lot of different worlds, which was a great opportunity for me to figure out which ones I wanted to stay in. And I left with a pretty solidified commitment to social service. I now run a nonprofit in Guatemala which, I think, came directly out of my experience there.

Could you talk more about your work in Guatemala?

I have a daughter adopted from Guatemala, and I’m a family physician with a degree in public health, and I had sort of got residence in family medicine throughout my career. I had always wanted to — ever since I left Oberlin — to do some work abroad, and that presented the opportunity. We started our work in 2008, and I lead at least two teams a year of medical people but also all other kinds of people. We’re collaborative with the villagers to improve the health of the people in their community. We have about 15 or 20 villages that we work with regularly, and we provide clinical care, but mostly give a lot of health education and preventive care and public health projects and education. We’ve dabbled a little bit in microfinance and economic development projects. I hope, at some point, we’ll run into somebody with the energy to help it fully develop, because our mission is to do all three of those things. Trying to improve health without improving education levels and [the economy] doesn’t work very effectively. I’ve never actually put it out there to the Oberlin community, but we’d love to have students come and join us. We take students all the way from high school through medical school, so it’s definitely an opportunity. … It’s been a really great learning experience for all of us, and I’m still at it.