Changing Narratives in Women’s Basketball

Photo courtesy of OC Athletics

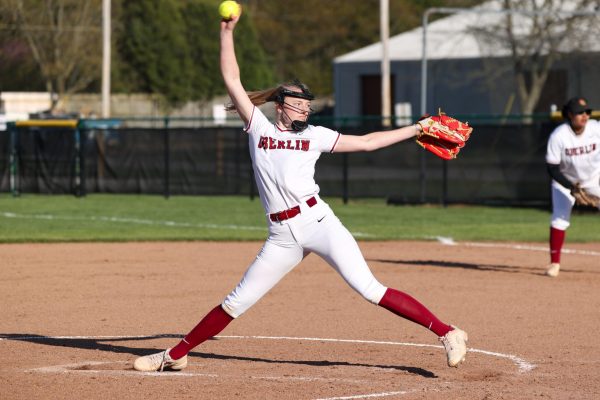

Members of the women’s basketball team take pride in their geographical, racial, ethnic, sexual, and spiritual diversity, but put their differences aside when they step on the court, uniting behind their desire to win. The team looks to repeat as North Coast Athletic Conference champions this year, with their first game scheduled for Nov. 10.

When I first stepped on Oberlin’s campus as a first-year last fall, I could feel the buzz of political activity. It was overwhelming yet thrilling to be a part of a group of students poised to change our social landscape.

What I soon realized was that there are sections of Oberlin that are dogmatic in their liberal ideology. It is a dogmatism that forces political homogeneity without room for mistake or disagreement.

This is fundamentally not what Oberlin stands for. As an institution with a deep commitment to social progressivism, excluding voices on the grounds of inclusivity is highly contradictory. Instead, I firmly believe that, at its core, Oberlin should be a place that fosters difficult conversations and disagreement in the name of advancing inclusivity and diversity. And while athletics is perceived as inconsequential to that mission, I contend that it works as an effective model for such dialogue.

I want to push back against the rhetoric that athletes at Oberlin do not respect the culture and ideals of this school. This is not to say that every team and athlete actively embraces Oberlin’s culture; rather, I argue that there are teams here that provide an excellent framework for practicing Oberlin’s core tenets of inclusivity and diversity. One such team is women’s basketball.

It starts from the top. Our head coach, Kerry Jenkins, is one of two Black head coaches in the athletic department, and our assistant coach, Chanel Green, is the only Black woman in the department. This plays directly into the team’s dynamic and our approach to recruiting.

“I’m a thorough recruiter and I actively seek diverse demographics when I recruit,” Jenkins said. “I think part of my mandate as a coach at a place like Oberlin is to bring disparate groups of players together to find commonality in our humanity.”

It is abundantly clear that he’s followed through on this strategy. The makeup of our team is not only unique to this campus, but to Division III basketball. It shows in our geographical, racial/ethnic, sexual, and spiritual diversity. We have players hailing from major cities like New York, Atlanta, Los Angeles, Boston, and San Francisco. Others come from rural and suburban settings in places like Michigan, Maryland, and New Jersey. We have one of the most racially/ethnically diverse teams on campus, with nearly half of our team identifying as POC.

Furthermore, our team is exceptionally queer (although this wasn’t intentional in recruiting) with over half the team falling under that umbrella.

Finally, we represent a spectrum of religious identities, including Judaism, Catholicism, Christianity, and Agnosticism.

I point this out not to boast or collect “woke points,” but to emphasize that there are a lot of different, intersectional backgrounds on the women’s basketball team. And frankly, this doesn’t encompass all the finer details of difference, such as family structures, academic interests, and fluctuations in personalities.

Despite this intermingling of varying identities and backgrounds, we make it work. We talk about our differences and simultaneously render them irrelevant. Our team is always finding the middle ground between a colorblind approach and the splintering nature of strict identity politics.

When we are off the court, conversations about religion, marriage, and childhoods are fair game. Whether they arise organically during lunch or intentionally begin out of curiosity, the conversations are a regular part of our interactions. These discussions provide an opportunity to better understand each other not only as teammates but as people who experience different forms of oppression.

The religious diversity of the women’s basketball team is our most glaring cause of disagreement. Religion is a topic that tends to be deeply personal and normally leaves little room for respectful discourse. In terms of my own religious background, my mother was Jewish and my dad is Christian. Growing up, neither religion was heavily enforced, the exception being time spent with my grandparents, as my grandfather had been a minister for 35 years. In the early stages of adulthood, I’m left with cultural aspects of Judaism, a skepticism for Christianity based on my queer identity, and virtually no connection to spirituality.

Two of my teammates, on the other hand, have a profound relationship with Christianity. It has been a major part of their lives at both the spiritual and community level. Both pray daily and hang Bible verses in their lockers. This was a stark departure from my predominantly secular and Jewish high school and neighborhood.

It took time before I got the courage to ask about their religious practices. Initially, we proceeded with caution. I skittered past my reservations of Christianity as a queer person, and they touched briefly on their powerful connection to it. As we got closer, it came up more. Eventually, so did our disagreements — the biggest over whether we believed in God. No amount of convincing or debating would result in agreement. But the unifier was respect. And so we moved on — sometimes we talk about it, but often times we don’t. As friends and teammates we arrived at a place of mutual understanding, and nothing more was needed.

This wasn’t as easy as it sounds. On my part, it demanded patience and the willingness to revise my decade-old narrative about Christianity. There were multiple times when I was tempted to discount, undermine, or generally disrespect their opinion. And I’m sure there were occasions when I did just that, to some degree. I’m not entirely certain what went through their minds, but I imagine that these talks weren’t the easiest for them either. While we’ve reached a place of relative peace, it remains a work in progress.

Once the team steps on the court, however, the narrative changes. Following our coach’s direction, we shift the focus to finding commonality in our humanity.

The gym sets the boundaries, and basketball is the equalizer.

In Philips gym, we are a unit, monolithic in our desire to win. Identity isn’t insignificant, but it becomes immaterial. We let the differences go and work hard day in and day out to be the best that we can be — that’s all there is to it. In that space, whatever religion we practice, whatever race, gender, or sexuality we are, it doesn’t matter. We are simply the Oberlin women’s basketball team.

With all that in mind, I have a couple requests for the greater Oberlin student body. The first is to reexamine how athletics and athletes can engage with the Oberlin movement for social progressivism. Not only does isolating our community exclude willing and helpful participants, but it also makes effective models for social change inaccessible. Let’s dismantle those barriers and start an exchange of information.

My second request is to ask and allow for potentially offensive questions. This requires the construction of well-maintained boundaries — it’s important to establish appropriate timing and context. On our team, we create space for and actively encourage these questions. The most meaningful changes occurred when teammates have found room to make mistakes, say the wrongs things, and diagnose areas where they might be ill-informed.

My last request is to find spaces where identity can both be discussed and rendered relatively unimportant. Create friendships with people where you can openly debate, converse, and disagree. Create friendships where the common purpose or source of unity transcends identity or politics.

Finally, I want to extend an invitation. If you don’t know where to start with all your potentially offensive questions, start with me! Shoot me an email, message me, or preferably, talk to me.