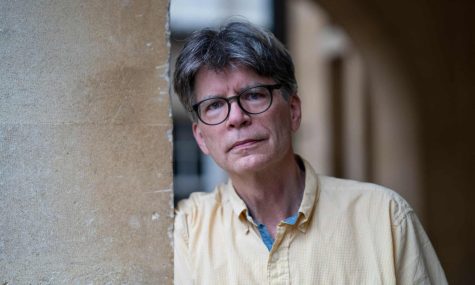

Blas Falconer, Poet

Blas Falconer, poet and author of the new book “Forgive the Body This Failure.”

Blas Falconer is a queer Latinx poet and editor who came to Oberlin to read from his new book, Forgive the Body This Failure, on Thursday, Nov. 15. Falconer teaches in the MFA program at San Diego State University. His other published works are The Foundling Wheel, A Question of Gravity and Light, and The Perfect Hour. Falconer received a 2011 National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship, the Maureen Egen Writers Exchange Award from Poets & Writers, and the Barthelme Fellowship, among others. He is a co-editor of the poetry section of the Los Angeles Review, co-editor of Mentor & Muse: Essays from Poets to Poets, and co-editor of The Other Latin@: Writing Against a Singular Identity.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Can you talk a bit about what you’ll be reading [Thursday]?

I’m going to be reading from my third full length collection, Forgive the Body This Failure. I’m still working out which poems I’m going to read. Generally, I like to create a kind of arc for the audience so that they have a little journey to go on. I’ve been talking a lot with [Associate Professor of Creative Writing] Kazim [Ali] about the book, and what I’ve been thinking about lately is how when I first showed him the book he said, “This is so sad.” And I’ve been thinking about that a lot. The last poem in the book is about how sometimes to get past grief you have to go through it, and I thought that might be an interesting way to begin a reading — with a poem that addresses that — and then maybe try and demonstrate how the book pushes through grief to arrive at a kind of reconciliation.

You’ve published one chapbook and three full-length books. What was it like for you to assemble and create a book and go through the publishing process?

It took me a long time to figure out the order [for the newest book]. I sent the manuscript to a few trusted readers — one of whom was Kazim, and I have a couple other poetry friends who I really trust — and I listened to their feedback and just sat with the poems for a long time. I changed the order a few times before I organized the collection by looking at four different themes, thinking about longing.

The first section addressed longing for someone who’s passed away. The second section was a longing for a parent from whom you might become estranged, so thinking about my mother and her mother, me and my mother, my son and his birth mother. The third section was about love — longing for someone who you’re not supposed to love, if you’re a gay person. And then the fourth section was about place, and again there’s the theme of exile, and the notion of a home where you might feel like you belong and thinking about that in terms of geography. A lot of those poems are thinking about Puerto Rico, which was my mother’s home and a place that I used to go to a lot as a child, but also a place where I don’t necessarily feel welcome anymore. That’s how it was organized, and then I just sent it to my publisher and they liked it enough to agree to publish it, and that was that.

Are there other themes and ideas like grief that you explore a lot in your work? Do you feel that differs from book to book?

I think one of the recurring themes I have in all my books is a sense of exile. One of my favorite stories from the Bible is the expulsion from the Garden. I feel I can identify with that story quite a bit. And that’s here, too, this sense of being an outsider — but also within this book, in particular, is the theme of how our bodies betray us. One of the ways that our bodies betray us is when they begin to fail. The poems in the book spend a lot of time focusing on the elegy, on people who are passing away or have passed away, and how we can process that grief.

Do you feel like those ideas have sort of changed and evolved over your writing career?

Absolutely. I’m 47 right now, and I have two young boys. And so I’m not only trying to process these larger questions for myself, but I’m also trying to help my young boys understand these larger issues and trying to teach them how to cope with grief and with longing. I think that the poems as a result have become much more streamlined and more bare. Because really, I think that I’m genuinely trying to understand something as I’m writing, and I’m trying to communicate it almost with my children as readers — my children when they are adults. I think a lot of the poems are in conversation with them, and some of the issues that they’ve wrestled with, as young children of two gay parents. They’re both adopted, so they have a lot of questions about their own origins. So I feel like I’m really trying to understand a lot of their larger questions and speak to them.

You’re an editor for two publications — can you tell me a bit about how you got involved with those publications and what they do?

I’m a poetry co-editor for The Los Angeles Review, and Vandana Khanna and I work together to promote poetry for that online journal. We started doing that because the editor from Red Hen Press, a boutique literary press in Los Angeles, invited us to take those positions and that’s how we ended up there. That’s a lot of fun. The second journal that I co-edit is called Mentor and Muse: Essays From Poets to Poets, and that originally started as a book project. My co-editors Beth Martinelli, Helena Mesa, and I put together this book of essays that invited poets who we felt had a very strong understanding of a particular poetic concept to write about that concept and encourage readers to explore that poetic device in their own work. And we loved doing that, and we were sad when it was over, so we decided we would kind of start it up again but this time online as a free journal for those who might be interested. This time it’s really targeting writers who have a pretty strong understanding of poetry and its history and want to continue pushing themselves and thinking about those poetic elements in more nuanced ways. So that’s how that came about.

How do you approach teaching in an MFA program?

I always tell my students that our workshops are really just an opportunity to talk about poetry. And not their poems in particular, but poetry. And when we do talk about their poems, the larger focus should be on how poetry works, the poetic devices. I ask them to think about the larger picture — we’re not just thinking about getting five or six poems ready for publication, but getting them to think about how poems work so that they feel confident well after the semester is over and they’ve graduated.

What I’ve been doing this semester is trying to give them a critical response to their own work, but I also want them to think about the poetic tradition and issues of literary craft. So each week I present them with some element of poetry, and then I kind of try and show them the history of that poetic device throughout the canon. So, for example, one week we looked at the poetic turn. We started with the Renaissance period and looked at the sonnet, and then we looked at sonnets over time and how they evolved from literary period to literary period, but then ended on looking at contemporary poems, both sonnets and non-sonnets and looking at the turn there. I do that because I want to encourage them to keep going back to the canon to see how different devices have been employed by different writers over different literary periods. Hopefully that’s been really helpful for them, to kind of encourage them to see the canon as this infinite resource from which they can learn.

Are there any craft or technique elements that resonate for you or are particularly helpful in your work?

It seems that with each book I rely on a few devices more than others. When that project’s over, I start to gravitate toward other devices so that I’ll maybe address my own obsessions in a different way. With this latest book I was really trying to write a spare poetry, and in order to create tension I relied a lot on the short line and enjambment. To me, that meant I could infuse the poems with a kind of tension that might not be as prominent if it were written along the line or written as prose. So I would say that I was thinking about the sentence and creating tension syntactically, but then also what kind of surprises I could make when I broke those sentences up in creative ways.

Is there anything else you’d like to add?

I guess what I could say is this: In an interview, Eavan Boland said that poetry begins with uncertainties. I think that with this book in particular I wanted to place myself in that mind space where I didn’t know the answers to the questions that were coming up for me and my family, and to honestly engage the questions that were before me. So the book documents that quest to understand some of the larger questions that I’ve faced as the father of two young boys.