Before Midnight: A Mature, Satisfying Conclusion to Linklater’s Trilogy

September 6, 2013

(Note: this review contains spoilers to the previous movies in the trilogy, Before Sunrise and Before Sunset.)

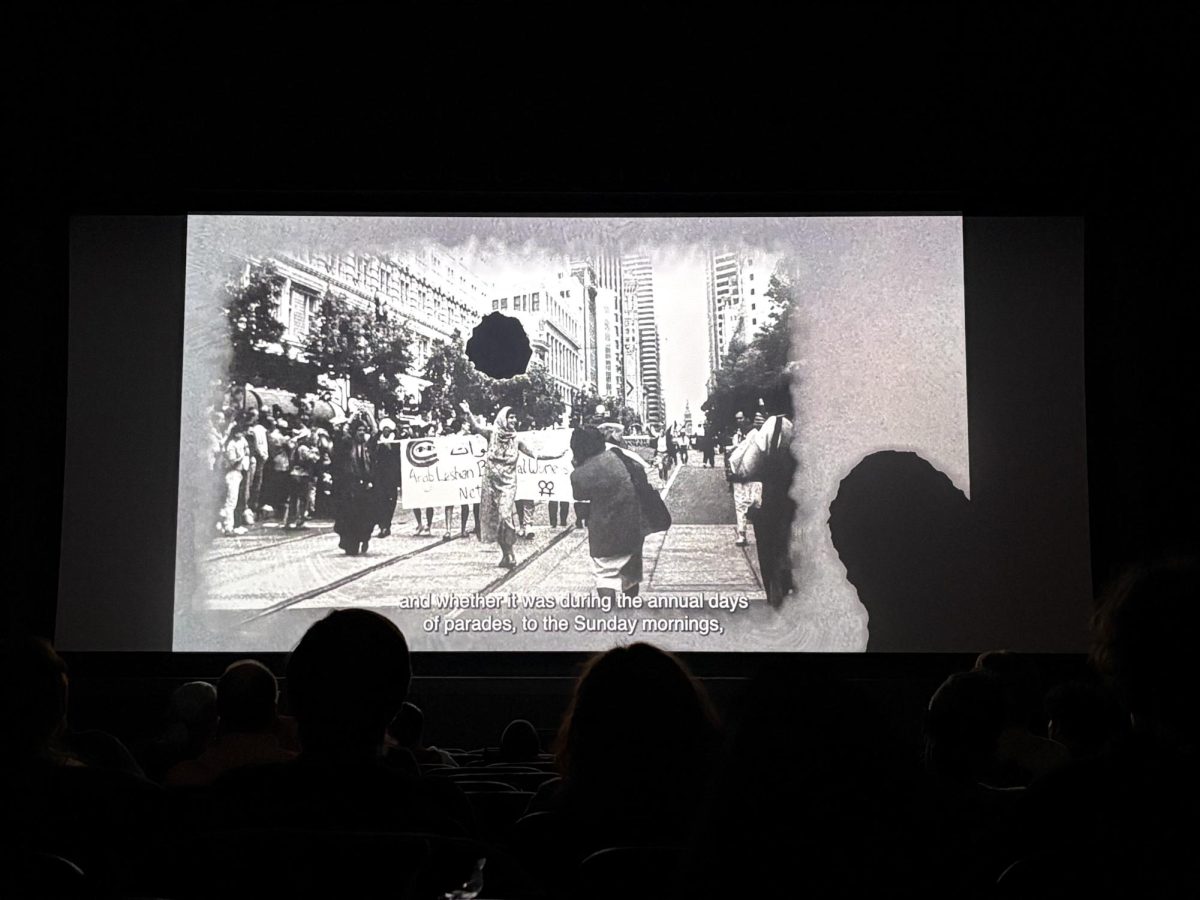

Director Richard Linklater first garnered critical attention in 1991 for the distinctive style established by his film Slacker, a low-budget production consisting of vignettes set in Austin, TX. The defining aspects of that style include long takes with minimal camera movement, a compressed timeframe with little or no plot and an overwhelming focus on character and dialogue. This summer’s Before Midnight, the sequel to Before Sunrise and Before Sunset, concludes Linklater’s romantic trilogy and continues the trend established by the previous two movies: a compressed timeframe and an almost uninterrupted conversation between the two lead characters, Jesse (Ethan Hawke) and Celine (Julie Delpy). Hawke and Delpy also helped Linklater to write the movie’s script, which comes through in Jesse and Celine’s onscreen chemistry and the ease with which they converse.

Arriving 18 years after Before Sunrise and nine years after Before Sunset, Before Midnight feels more mature and developed than its predecessors; while the first two movies in the series had the potential to connect deeply with viewers and featured some of the best-developed characters in film, the standards set by those two films are raised by the work that Linklater, Hawke and Delpy present in Before Midnight. The film juxtaposes the struggling relationship of Jesse and Celine, now married and with twins, against the stunningly beautiful landscape of a Greek villa where the two are vacationing. The movie also provides Delpy’s and Hawke’s characters with more social context than the previous two films allowed: In addition to conversing and interacting with one another, the two eat dinner with friends and guests, and Jesse’s son Hank (Seamus Davey-Fitzpatrick) plays a crucial, albeit brief, role.

Linklater develops the film’s themes, namely, the difficulties of sustaining romantic connections in the face of mundane and quotidian realities, in a couple of ways. Throughout the first third of the film, the themes are introduced and developed explicitly through a dinner table conversation — the closest the film comes to being heavy-handed. This frankness with which the characters discuss love’s beginnings and ends is balanced by the exquisite subtlety of the conversation between Jesse and Celine that runs the last hour of the film.

Both of their characters have grown and changed since the last installment, but at the same time the viewer recognizes in the 41-year-old Jesse and Celine the same quirks, facial expressions, flaws and charms that were present when the two were starry-eyed 23-year-olds in Before Sunrise. Delpy especially shines in portraying the difficulties with which Celine struggles as a woman — the ways that patriarchal expectations and assumptions continue to haunt and oppress even independent and successful women, the double standards under which women live and work, and the subtle forms of sexism that men can demonstrate even when they are sensitive and sympathetic to feminism.

What makes Before Midnight stand head and shoulders above its admirable predecessors is the way that Linklater is unafraid to raise the stakes for his characters. In previous installments, romantic tension was essentially the only source of conflict in the movies — would Jesse and Celine stay together, keep in touch, get back together? Here, though, the complexities of family intervene, and when Jesse and Celine’s conflicts come to the fore, the depth of anguish and harrowing intensity that Linklater, Hawke and Delpy portray belong in the upper echelons of cinematic achievement.