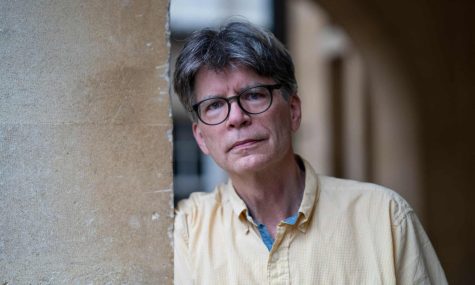

Ti Ames, Director of Kander Lab Series Show “The Brothers Size”

Ti Ames.

Ti Ames is a fourth-year Africana Studies and Theater major from Charlottesville, Virginia. They are directing The Brothers Size for their senior capstone project. The play is a part of The Brother/Sister Plays, a trilogy by Tarell Alvin McCraney, who co-wrote the 2017 Oscar Best Picture Moonlight. The play explores Yoruban spirituality and the Orishas, who are the personification of forces in nature and human endeavors. Their spiritual roles have been translated through different cultures and are prominent in many religions. The show runs from March 7–10 in the Kander Theater. Tickets are $5 and are available at Hall Auditorium and online through Central Ticket Services.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Can you tell me what this play is about?

The show is based on the Yoruba spiritual framework. Yoruba is a religion that comes out of West Africa that has been transcribed through the Middle Passage up through the Caribbean and into the United States. It’s based on the idea that you have these forces of nature that control the earth and everything surrounding it.

You’ve got Oshoosi who is the Orisha of hunting, you’ve got Ogun who’s the Orisha of labor and iron, and then you’ve got Elegba who’s the Orisha of the crossroads and doorways. Oshoosi is 19 years old. He was just released from prison and he has moved back in with his older brother, Ogun, who owns an auto mechanic shop. When Oshoosi was in prison, his cellmate was named Elegba, and it turns out they’re all from the same town in Louisiana. The show takes place about three months after they both get out of prison. I don’t want to give too much away, but basically, it’s just Oshoosi trying to figure out what to do, being a Black man in the South who now has a record. It’s about his experience navigating life, the law, the police, and what it’s like to have an older brother who didn’t visit him in prison.

What has your approach been to directing this play?

When I became an actor, acting was very much based in Western doctrines and Stanislavski-type methods. For this show, I decided to go in a different direction. We’re doing something called Soul Work and call and response, which is very much rooted in Black aesthetic.

These two different principles work very similarly and they work together. The term Soul Work was coined by Dr. Cristal Chanelle Truscott. Her idea is that Western theater is all based in individual work and asks, “What do I want? What do I need in order to keep going in the show?” Soul Work asks, “What does my community need?” It goes from an individualistic view of a show to a community view of the show.

So it takes a little bit from this idea of action and reaction in Stanislavski, but the call and response kicks back on that. I don’t have any set actions or objectives for my actors. I told them, “You can have a basic understanding of what’s going on here, but unless you’re actually sitting there and receiving what the other person is giving to you, there’s no possible way to give anything back. So your action and objectives will change every single show, every single time we run the scene. If it happens to start forming into a general idea that kind of continues, sure, let’s go with that. But if something new happens, which every single run of the show [it does], run with it because you now have a new call that you have to respond to.”

How has the show been a collaborative process?

What I didn’t mention about the show that I’m excited to explore, is that it talks a lot about Black queer masculinity. This campus is full of Black folk. It’s a smaller community because this is a small private white institution, but we exist; we’re here, and the Black queer community is even smaller. What’s been beautiful about this show is that it’s brought everyone out from the woodwork to work on it. My entire set was done by Black artists. There’s a massive mural on the back wall done by them. I’m very lucky and very blessed to have people who want to work on this show. It’s been really great to not have to do this by myself, and to work with people who are just as enthused about this and just as dedicated as I am.

What sort of important issues do you think this play addresses?

There’s so much! I mean, first of all, you’re talking about Black queer masculinity, which is something that is not talked about a lot, period, wherever you are. When most people think about Black queer people, they think about Black gay men who are more feminine-presenting. And those are great and wonderful people, but we don’t talk about the other facets of Black queerness, especially when it comes to men. So it’s nice that this show really hits that on the head, talking about what it means to be a Black man, raised as a “traditional” Black man with very masculine qualities, who was forced to be strong every day of his life, and to be an example for everyone in his life.

The show is also based a lot on speaking stage directions out loud. Sometimes a character will say “the law runs up on him” or something like that, which … shows how the law is everywhere. Being Black in America is not a fun thing, especially being Black and queer in America; you’re automatically a target.

It also talks about what it means to be from the South. I’m from the South, so I think that’s why it means so much to me. A lot of the show talks about the mud, and what it means to be stuck in mud, or stuck in dirt. The show has a very swampy quality because it takes place in the Bayou.

We also base a lot of the show off of Angola prison, which is the largest plantation prison in the country. It still exists. It started out as a plantation during slavery. Now in 2019, it still exists as a slave plantation, but it happens to be a prison. It’s mind-boggling to me that these places exist.

How has dramaturgy and Yoruba Spirituality been a part of this show?

[College junior] Miyah Byers is our dramaturg. She’s also my assistant director and she’s also in the show. She has done so much. She did a lot of work researching Yoruba and figuring out how we can carefully and respectfully approach the show when it comes to spirituality. Yoruba is a very, very serious spirituality. There’s a difference between religion and spirituality being that religion is something that you do and spirituality is something that you are.

We have to be very careful when dealing with Orishas because we have to be respectful of the fact that this is not something that we do every day. Nani Borges is the only person who practices Yoruba in our cast, so a lot of questions go to her. We dedicated the space to the Orishas and we have little offerings to each of them in the corners of the room. When we first walked into this space a couple of weeks ago, we blessed the space with Florida water, which is something that’s used for a lot of spiritual ritual and African aesthetics. We blessed it to communicate to the Orishas: “You’re welcome here. This is your space.” We want to respect them and respect their place in the show. We also respect the fact that there are some things we can’t do because we don’t want to be sacrilegious or offensive. Personally, and this might sound kind of crazy, I’ve seen the power of Orishas, and they don’t play around. So it’s nice to be able to dedicate the show to them. All of us may not believe it to the same extent, but we respect it, and that’s the most important part. And I would hope that the audience would also do that even if they have no idea what Yoruba is.

What role have music and dance played in this production?

A massive role! We have an amazing music director, [double-degree senior] Eli Heath, who’s graduating this year, and this play is part of his Africana honors project. He is a white man who I love dearly, who understands what it means to be a white person in a Black space. A lot of his role has been figuring out what the live music in the show is going to sound like. He works with Khalid Taylor, [OC ’17,] and [Conservatory first-year] Anthony Anderson, who are doing most of the singing and the dancing in the show. We also have [College senior] Nani Borges working with us, and she is an amazing choreographer. I love having her on this piece. She’s also in the show as an ensemble member.

With Eli, Nani, and Khalid — who’s also choreographing — we’ve created something that we like to call the counterpoint melody. It started on our first day of actual rehearsal after the read-through when I just asked Khalid and Anthony and [College junior] Jaris Owens to start the prologue of the show, which is like an invocation or incantation. And I was like, “Just play around and see what comes out of your mouth, we’re just gonna record it and keep track of it and if we like it we’ll keep going with it, and if we don’t, we’ll scratch it and we’ll start something new.” And Khalid came up with this melody that gets stuck in my head every single time we do this. Eli picked it up and just started creating music based off of it.

And along with that, we have a great playlist and soundtrack of music. A lot of the music is sung live by our actors, but we are also working with a lot of recorded music from like late ’90s, early 2000s really bringing people back into like, “This is what Black life felt like at this point.”

We’re also pulling from spirituals, Black church, and all these different avenues of music and dance to create this massive show. There’s even capoeira at one point with a berimbau being played. There’s a little bit of everything.

What do you hope the audience walks away with?

I hope people understand that there’s more out there than we — the hegemonic majority of Oberlin College — understand. We don’t talk a lot about Yoruba, Black queerness, or about things that are really hard to talk about. And this show puts it right in your face so you can’t ignore it anymore. I would love for people to walk away and talk about it.

The “what-ifs?” of this show are so expansive and can go in so many different directions. I want people to talk about this show. I want people to be like, “What did this mean? What is going on?” because that’s what we spent the last three months doing. Just last night we had a massive, massive “Aha!” moment. We open in four days and yet we’re still having these discoveries. I want the audience to keep discovering with us, that’s my main thing. Also, I just want them to enjoy themselves.