Eight Years In, NEXUS Fight Continues

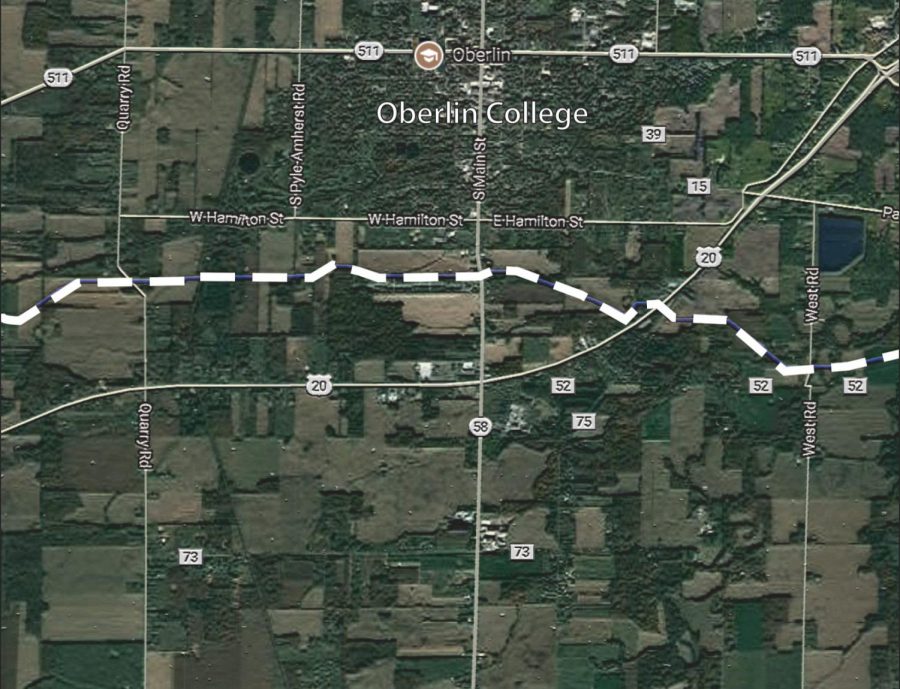

For the better part of a decade, Oberlin residents, City officials, and College students have been involved in a battle against NEXUS Gas Transmission, a 256-mile pipeline extension that was ultimately built through Oberlin city limits and continues to be opposed in court. The pipeline, which begins in the eastern part of Ohio and travels through the state before connecting to a transfer point in Michigan, is designed to carry up to 1.5 billion cubic feet of natural gas daily. The project represents a joint partnership between DTE Energy and Enbridge, Inc., and went into operation in September 2018.

Opponents of the pipeline have argued that, due to insufficient demand, building the pipeline was not actually in the public interest. NEXUS is undersubscribed, meaning that only a portion of its full capacity to transport gas is actually used. Further, a significant portion of its subscribed capacity is intended for foreign markets in Canada, not American consumers — nearly three-quarters of the gas transported by the pipeline every day is destined for Canada, the City of Oberlin argued in a brief filed March 2019. Opponents have further expressed concerns in court about the pipeline’s proximity to residential structures, should some kind of disaster occur.

The federal agency that oversees the construction and siting of natural gas pipelines like NEXUS is the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission. Established in 1977, FERC comprises five commissioners that are appointed directly by the president.

In recent years, some have critiqued FERC for a perceived willingness to greenlight pipeline projects that create undue environmental and health burdens for the communities they are sited within. Specifically with regard to NEXUS, the City of Oberlin has argued that FERC did not seek adequate justification in approving the use of eminent domain to provide space for the pipeline to be built through the city.

The most recent legal decision in the NEXUS fight came down in September 2019, when the District of Columbia Court of Appeals largely sided with the pipeline but did agree with the City of Oberlin that FERC needed to better address concerns about the gas it was transporting to foreign markets.

“[FERC] failed to adequately justify its determination that it is lawful to credit Nexus’s contracts with foreign shippers serving foreign customers as evidence of market demand for the interstate pipeline,” the decision read. Ultimately, the court decided to remand without vacatur, meaning that FERC will need to provide further justification for the decision but, in the meantime, the pipeline’s operations can continue uninterrupted. As of yet, FERC has not officially responded, although attorney Carolyn Elefant, who represents the City of Oberlin, said that this timeline is not unexpected.

Last year’s ruling represented just the latest development in a nearly decade-long saga that began in 2012, when NEXUS began to enter into precedent agreements to transport natural gas. The intention of these long-term contracts was to demonstrate sufficient market demand for the pipeline, one of the prerequisites for FERC approval.

Between 2012 and 2015, NEXUS gathered commitments from eight different entities that represented approximately 60 percent of the proposed pipeline’s daily capacity, according to the September court decision.

Then, in November 2015, NEXUS sought FERC authorization to construct the 256-mile pipeline extension under Section 7 of the Natural Gas Act, which grants FERC oversight of such projects. The City of Oberlin opposed NEXUS’ application, arguing that the project had not effectively demonstrated demand for the gas it would transport, nor proved that building the pipeline would be in the public interest or protect public safety.

The City also cited the Oberlin Codified Ordinances, commonly referred to as the Community Bill of Rights. Codified in 2013, the ordinances are meant to prohibit the development of extraction infrastructure within city limits, including natural gas pipelines.

John Elder, OC ’53, has been heavily involved in local efforts to oppose the pipeline through his role as vice president of the Oberlin-based organization Communities for Safe and Sustainable Energy. He said that when CSSE became aware of plans to build the NEXUS pipeline in 2013, members worked with the Pennsylvania-based organization Community Environmental Legal Defense Fund to put together the ordinance.

“CELDF provided the basis for our Oberlin Community Bill of Rights and Obligations Ordinance, which both affirms the rights of nature and bans fracking and fracking infrastructure,” Elder said. “CSSE is the organization that got that ordinance passed, so it became city law. It’s on the basis of that ordinance that the City of Oberlin has opposed the NEXUS pipeline, and [Oberlin] is at this point the only city that has carried all the way to the federal appeals court a petition to have a rehearing of the issuing of the license for NEXUS.”

Undaunted, NEXUS continued to press ahead with a planned construction route going through Oberlin as well as other Ohio and Michigan communities.

In July 2016, FERC released a draft of its environmental impact assessment, and allowed time for responses from petitioners — namely the City of Oberlin and the Coalition to Reroute NEXUS. Both groups filed formal responses in August of that year, and the final environmental impact statement was released in November. The final impact statement did not advise FERC one way or another whether to proceed with the project, but it did argue that “natural gas transmission pipelines continue to be a safe, reliable means of energy transportation,” citing safety standards imposed by the Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration, an agency within the U.S. Department of Transportation.

“One reason FERC said that proximity didn’t matter was because pipeline safety laws don’t have any restriction on proximity to houses,” Elefant said. “The company said that they were going to abide by the safety regulations and that they would operate it safely. We argued that that was ridiculous.”

The City of Oberlin’s March 2019 brief filed in the district court noted that the final environmental impact statement found 178 residential structures within 50 feet of the pipeline’s planned route, as well as another 62 residential and commercial ongoing development projects. Oberlin’s legal team hoped to use these concerns to shut the project down, but was unsuccessful.

“We said to FERC, look, even though [PHMSA guidelines] say it’s safe, there is a risk that if something does happen, it’s going to be catastrophic,” Elefant said. “So why don’t you just move it away? That would be a rational response. We didn’t get anywhere. They just said, ‘The company says they’re going to operate safely, [and] that’s all we care about.’”

The environmental impact assessment was one of the final formal steps taken before FERC granted NEXUS “a Section 7 certificate of public convenience and necessity,” in August 2017. In granting the certification, FERC maintained that NEXUS’ precedent agreements sufficiently proved market demand and that the pipeline’s construction and operation did not represent a threat to public safety. Then, in late December of the same year, a district court ruled that NEXUS would be able to use eminent domain to acquire property necessary to the pipeline’s construction. In July 2018, FERC denied a request for a rehearing filed by the City of Oberlin.

Eminent domain is a process by which government agencies can compel private landowners to turn over their property for public use, provided that the landowners are compensated for the loss. In the case of NEXUS, the pipeline’s mission was deemed to be in the public interest, and eminent domain was approved. In May 2019, Carol Banta, an attorney representing FERC, argued that the use of eminent domain was minimal, as 93 percent of the pipeline was constructed without compelling landowners to sell their property.

“Even if it’s one percent of eminent domain needed, that’s someone’s property being taken, and that raises constitutional issues,” Court of Appeals Judge Robert Wilkins countered. Still, because the court did not find sufficient cause to halt the pipeline’s operations, the case was remanded and NEXUS’ operation was not interrupted.

As City officials and Oberlin residents, including Elder, have worked to oppose NEXUS through legal channels, Oberlin College students have also consistently organized around the issue.

“Different people had different reasons why they thought it was a problem,” said College fourth-year Rachael Hood, who is a leader in Students for Energy Justice. “One that everyone agreed on is that the risk of pipeline explosion, especially [in] Oberlin, was really concerning because [NEXUS] is right next to a large residential development. … And then I think, to different degrees, a lot of people — including myself and SEJ — are really concerned about fossil fuel industries and extractive industries perpetuating climate change.”

While students and City officials are largely united in their desire to stop NEXUS’ operation through Oberlin, there have been moments of significant discord between the two groups. In March 2018, during a regularly-scheduled meeting, City Council voted 4–3 against a potential settlement with NEXUS — a move supported by students (“Final Pipeline Vote Rejects NEXUS Settlement,” The Oberlin Review, March 9, 2018).

At the previous meeting, however, it appeared as though the council was ultimately going to go the other way. Caught off guard, students showed up to protest in a manner that rubbed some councilmembers the wrong way.

“I am saddened by the suggestions — either implicitly or explicitly, some by those who don’t know me and some by those who do — that I lack integrity or principles,” Councilmember Kristen Peterson said.

Looking back two years later, Hood — who read a statement at the March meeting apologizing for the way that students’ actions had been perceived — said everybody was doing what they thought was right for Oberlin.

“There was definitely tension at that time, which is unfortunate,” Hood said. “I think, ultimately, everybody involved was just trying to do the right thing. A lot of the City Council members who were thinking about accepting the settlement had been really vocal against NEXUS. And the City put up a lot of money to pay for the lawyers in the legal battles with NEXUS. That’s really admirable — we just had disagreements over whether or not to accept the settlement.”

Today, NEXUS remains operational, although opponents in Oberlin remain hopeful that they may, one day, be able to shut it down. Elefant says there’s not necessarily a set timeline for what happens next.

“I think the problem for FERC is that they’re sort of stuck, because we did raise an issue that nobody saw coming,” Elefant said, regarding the argument that the pipeline could not simultaneously serve the public interest and be undersubscribed. “I don’t think they have a standard response. So, I think internally they’re trying to decide what to do. … I think that they have to come up with some sort of way to justify the pipeline without that gas in there. And I’m not sure if they know how to do it at this point.”