Appalachian Storage Hub Development Sparks Concerns

Appalachia has been a hub of fossil fuel extraction for over a century, and the Ohio Valley Environmental Coalition has been leading anti-pollution efforts in the region since Dianne Bady founded the organization in 1987. In 2017, months before her death, Bady was sifting through industry magazines and noticed several proposed projects related to plastic production. Slowly, she stitched together a picture of what was to come: a massive petrochemical complex, now known as the Appalachian Storage Hub, spanning Kentucky, Ohio, West Virginia, and Pennsylvania. This facility would store fracked natural gas fluids in underground caverns and process these petrochemicals into the building blocks of plastic.

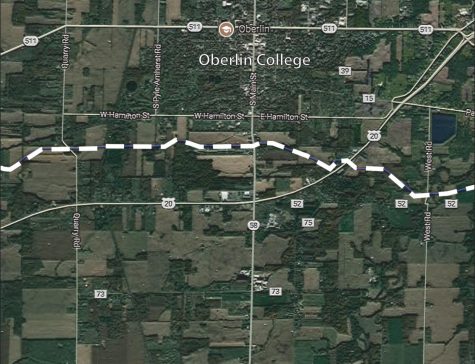

The coal industry has traditionally paid the bills for Appalachian families, but natural gas has been on the rise since the shale boom began in the early 2000s. Fracking projects swept across the region, along with pipelines to transport fracked natural gas — including the NEXUS pipeline that runs through Oberlin. For more on NEXUS, see “Eight Years In, NEXUS Fight Continues” on page 18.

Still, the industry’s future is uncertain; it has expanded rapidly in part thanks to the low market price of natural gas. However, affordability is also one of the industry’s greatest challenges: it has prevented gas companies from generating the profits promised to investors.

“There’s just a glut of natural gas, with nowhere to go,” says Dustin White, OVEC’s project coordinator focusing on the Appalachian Storage Hub. Companies are looking for ways to increase demand for their product, and it looks like they may have found one in ASH.

It’s important to understand the role of the proposed storage hub in the petrochemical supply chain. It all starts with natural gas, which, importantly, is not actually one type of gas; rather, it is a combination of methane, ethane, propane, butane, and more. It is usually extracted through a process called fracking, in which a briny liquid is used to drill down through layers of shale to release pockets of gas.

While methane is commonly used to generate electricity, heat buildings, and fuel industrial facilities, ethane is the primary chemical of interest for the Appalachian Storage Hub. If the petrochemical complex is built, fracked ethane will travel through a web of pipelines connecting extraction sites to the storage complex. Once there, it would be stored in giant underground caverns, mostly abandoned coal or salt mines. It would then travel via pipeline to ethane cracker plants, where the chemical would be heated and broken down into ethylene. The complex would also include propane dehydrogenation facilities, which convert propane into propylene. The ethylene and propylene would then be shipped overseas to manufacture plastic. The storage caverns and chemical plants will straddle the Ohio River from Northern Kentucky through southeast Ohio, across much of West Virginia and into southwest Pennsylvania.

Beyond the general picture, the exact scale of the project and locations of specific pieces of infrastructure are being kept under wraps by Appalachia Development Group. The company describes itself as the “strategic driving force of the Appalachia Storage and Trading Hub.”

“There are no exact numbers except for what is already in place,” White cautions. “Appalachia Development Group has suggested up to five large ethane crackers with the potential of other smaller crackers, several massive underground storage sites, a potential “six-pack” of “thirty-two” inch pipelines running the length of the Ohio River, several thousand miles of feeder pipelines, and hundreds of additional chemical refineries.”

Every type of proposed infrastructure and each stage of the petrochemical process can create environmental hazards. White describes this as “cradle-to-grave” environmental damage.

“From the moment the natural gas liquids are fracked to the plastic waste that is the end product, there’s no way that it does not harm human health in some way,” he said. “So it’s completely overarching.”

Many of these dangers are well-understood. Fracking wells are known to leak and pollute nearby groundwater: A 2017 study by Environmental Science & Technology examined 31,481 wells over a 10-year period and found 6,648 serious leaks. Fracking wells also release enormous amounts of raw methane — a greenhouse gas 84 times more potent than carbon dioxide — in the first two decades of release into the air. The storage hub’s role in propping up the domestic natural gas industry could also have negative consequences for the climate, further solidifying the U.S.’s dependence on fossil fuels.

These risks to environmental safety and public health are only the tip of the iceberg. The pipelines through which natural gas travels are largely shielded from government regulation and frequently leak or cause explosions. The cracker plants, in addition to emitting hazardous air pollutants such as carbon monoxide and particulate matter, would also release pollutants into surface water.

“There’s more of a potential that the underground storage [facilities] will contaminate groundwater, whereas the facilities set above ground like the cracker plants will contaminate surface water,” White said.

The entire complex is built around the Ohio River, thus jeopardizing the water supply of about 5 million people. Finally, increased plastic production would exacerbate plastic pollution in large bodies of water around the world.

Other dangers to public health are uncertain, in part because the industry is not releasing information about the cracker plants and other aspects.

“As far as a lot of the pollution and chemicals, there [are] a lot of them we don’t know, for the simple fact that a lot of this stuff is proprietary knowledge,” White explained. “But some of the pollution will cause things like cancers [and] increased asthma.”

Destructive infrastructure projects are in no way new to Appalachia. As White recounts, this is just the latest in a long history of extraction and pollution in the region, which has taken a toll on residents’ health.

“It really just compounds the issues that are already there,” he said. “Instead of taking steps forward to clean up, we’re actually taking steps back to make it worse.”

These environmental hazards place the storage hub under the purview of several regulatory agencies, including state-level Environmental Protection Agencies. White describes a chaotic regulatory process.

“The industry has never built anything like this in our region,” he said. “So we’re kind of learning the regulations as the regulatory agencies are making [them] up.”

The Clean Air Act and Clean Water Act mandate that certain polluting facilities receive permits in order to limit their environmental impacts. A cracker plant planned for Belmont County, Ohio, has received two permits from the Ohio EPA — one for air and one for water pollution. The water permit allows the plant to release pollutants into the Ohio River, including 20 kilograms of phosphorus a day and close to four kilograms of zinc; the air pollution permit caps annual carbon monoxide emissions at 500 tons, nitric oxide emissions at 144 tons, and particulate emissions at about 72 tons.

According to the Ohio EPA, the permits were “written to be protective of human health. Adverse health and welfare effects are not expected.” The agency says it is “confident the facility will adhere to the permit.” Environmental activists in the region say that regulatory agencies are too deferential to extractive industries and often fail to protect the health of local residents.

OVEC is wasting no time organizing opposition to the project, which is still in the early stages. As of right now, a company called PTT Global Chemical is still seeking financial support to build the previously mentioned cracker plant in Belmont County. The first of the hub’s chain of underground storage facilities is also in the works, 12 miles south of the cracker plant in Clarington, Ohio. Both sites lie on the Ohio River.

At this point, OVEC is focusing on educating people who could be affected by the storage hub so that an engaged public can spring into action once construction is announced. In Belmont County, residents are just beginning to learn about the incoming cracker plant and larger petrochemical complex. No one knows when PTT Global Chemical will secure the necessary funds to begin construction. Barb Mew, a resident near the proposed ethane cracker plant in Belmont County, Ohio, told the West Virginia newspaper, Charleston Gazette-Mail, last August, “It’s kind of a piecemeal approach where it’s a little bit at a time, where you don’t realize the scope of what’s happening and by the time you do, it’s too late.”

PTT Global Chemical did not respond to request for comment.