Water Management in Oberlin: An Overview

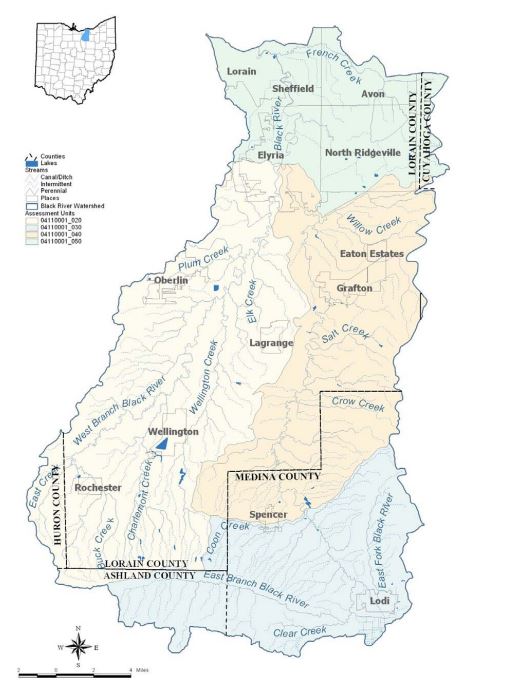

The Black River Watershed, where the City of Oberlin collects its drinking water.

For decades, environmental activists and agencies in Northeast Ohio have worked to ensure safe drinking water for residents and safeguard surface water against pollution. In the mid-20th century, the picture was bleak: The Black River, a tributary of Lake Erie which runs through Oberlin, was nicknamed the “River of Tumors” because of dead fish littering its coastline. When the Cuyahoga River caught fire in 1969 as a result of industrial waste, Congress took action to pass the Clean Water Act.

“Cleveland has a special place in the history of environmental legislation in the sense that when people see rivers catching on fire, they find that troubling and they’re actually motivated to take action,” said Paul Sears Distinguished Professor of Environmental Studies and Biology John Petersen.

Like its much-larger neighbor, the City of Oberlin also has a long history with water management. Oberlin has operated a public treatment plant since 1887 to provide residents with safe drinking water. According to the Oberlin Heritage Center, before the construction of water treatment facilities, residents primarily obtained their water from private wells and Plum Creek. This put individuals at risk of waterborne diseases like typhoid. Additionally, use of these private wells in place of a centralized supply led to an inadequate response to a fire that swept through the downtown area of Oberlin in 1882. This incident prompted voters to adopt a bond measure to construct a city water supply system. With an additional small sum of money provided by Oberlin College, the City built Morgan Street Water Works.

Oberlin has always been a town and college of firsts, and water was no exception. OHC notes that Oberlin was the first municipality in America to install a lime-soda water softening plant. Soft water — water with low concentrations of dissolved minerals — is easier to use for cleaning and bathing because it lathers with soap more easily.

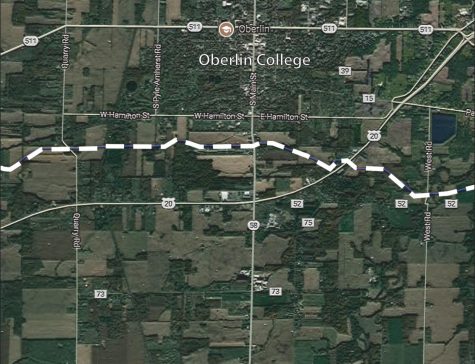

Today, the city’s water treatment plant is located on Parsons Street. The water that Oberlin residents drink comes from the Black River, which is Oberlin’s local watershed. Unlike sources such as groundwater, however, water running on the surface can be more easily compromised by industrial and agricultural runoff.

“The principal problem [in Oberlin] is farming,” said Petersen. “You get agricultural runoff. People worry about pesticides, but mostly the problem is fertilizers that travel into the river systems. And when they get into Lake Erie, they cause algal blooms.”

Hazardous algal blooms have been a severe problem for Northeast Ohio in recent years. When too much fertilizer makes its way into the water, it fuels the growth of algae, which depletes the water’s oxygen supply. When oxygen levels become dangerously low, they can create a “dead zone” in which aquatic plants and animals cannot survive. In 2014, an algal bloom in Lake Erie made Toledo’s drinking water supply unsafe to drink. Rivers are also potential breeding grounds for algal blooms, especially if they are slow-moving. For more on current challenges facing the Great Lakes, see “As Great Lakes Water Levels Rise, Connection to Climate Change Unclear” on page 60.

In Oberlin, the drinking water supply is generally safe to consume, as it currently meets the Environmental Protection Agency’s legal limits for contaminants found in the drinking water. Trace amounts of some chemicals are often found in municipal water supplies but may not be present in concentrations high enough to cause health or cosmetic damages.

The EPA regulates levels considered safe for consumption through the Safe Drinking Water Act. However, the National Academy of Sciences estimates that between three and 10 percent of municipalities violate safe drinking water standards each year.

Furthermore, some nonprofits feel that EPA standards are not stringent enough to sufficiently protect public health. The Environmental Working Group is one example of an organization that sets independent standards for safe drinking water. Although Oberlin is in compliance with federal standards, the water supply failed to meet eight of EWG’s standards in 2019.

Oberlin exceeded EWG’s health guidelines for nitrates, a component of fertilizer that fuels algal blooms, and total trihalomethanes, which, at high levels, can cause cancer and adverse reproductive outcomes. Other substances, such as bromodichloromethane and chloroform, were also found in Oberlin’s water supply above EWG’s suggested limits, but these chemicals — all known carcinogens — are not currently regulated by the EPA.

One of the best ways to protect our drinking water is by preventing chemicals from entering into water systems in the first place.

“The most important area around the river system is the area most immediately adjacent to the river,” Petersen said. “Riparian area is the name for the area right along a riverbank. Vegetating the riparian area, legislating so that you regulate and expand that area. But the other thing has to do with when farmers apply fertilizer, how much they apply, and in what forms they apply a fertilizer.”

Northeast Ohio has made immense progress improving regional water quality over the last several decades. However, numerous threats to clean water remain, and past achievements can be reversed. In January, the Trump administration modified how the EPA enforces the Clean Water Act, allowing companies to dump pesticides and other pollutants into streams and wetlands. The struggle to secure clean water for local residents is one that will surely continue on in the years and decades to come.