As Great Lakes Water Levels Rise, Connection to Climate Change Unclear

Water levels across the Great Lakes System are reaching record highs.

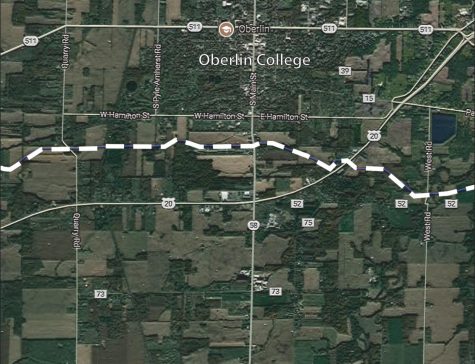

Water levels in Lake Erie — and the Great Lake system overall — are higher this year than they’ve been in over a century, and for people who live and work next to the water, the impacts can be significant. This past winter alone, a beachside park in Northeast Ohio lost 45 feet of land in just 10 days due to erosion; homeowners around Lake Erie scrambled to build emergency shore protection to shelter their properties from high tides; and strong winds along the water encased lake-side New York houses in uncanny ice tombs. While these events are cause for alarm, it’s not yet clear whether they are the direct result of carbon emission-caused climate change.

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers has been collecting data on water levels in all five Great Lakes since 1918. It’s normal for the lakes’ levels to shift month to month and year to year, as the ratio of rainfall to evaporation changes with the seasons. Recently, however, Lake Erie’s water levels reached a record high.

“The records that we saw in February was the highest February level that we saw in the past hundred-plus years,” said Lauren Fry, the technical lead for Great Lakes hydrology at the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers’ Detroit district office. “I think it’s worrying to a lot of people.”

A host of natural and economic ecosystems are impacted when lake levels rise. Parks can be destroyed by erosion, and homes can become flooded. Wetlands are inundated with water, which can kill certain forms of aquatic vegetation. Both recreational and commercial boating are also affected.

“It’s something that impacts a lot of people because there [are] so many people across the Great Lakes on the shoreline,” Fry said. “There [are] a lot of people who rely on the shorelines, either because that’s where their property is, or that’s where they … have businesses. We hear about marinas [that] are having to close sometimes because their dock power is underwater, [and] that’s not safe. So certainly we worry about it.”

According to Assistant Professor of Geology Rachel Eveleth, who studies the Great Lakes, all water systems depend on three core variables: runoff, precipitation, and evaporation. However, unlike rising sea levels — which are primarily caused by melting ice glaciers and are commonly cited as one of climate change’s most dangerous consequences — the cause of the Great Lakes’ rise is a little more complex.

“If you’ve got high levels of precipitation and runoff, and those levels exceed the amount of water leaving by evaporation, then you’re going to see an increase in water level,” Eveleth said. “Right now, water levels are at a record high, as we’re coming off of last spring’s record-high precipitation levels and really high runoff. That was related to the same precipitation events that caused all the flooding through the Midwest last year. … That added just a ton of freshwater to the system, way more than was leaving from the evaporation.”

The Great Lakes’ water levels generally cycle between highs and lows over the course of several decades — before last year, record highs occurred in the 1980s, followed by lows in 2013. But there is considerable evidence to suggest that extremes on both sides will be exacerbated as a result of climate change.

“The amount of precipitation we’re receiving now is almost unprecedented,” said Scudder D. Mackey, chief of the Office of Coastal Management at the Ohio Department of Natural Resources. “Whether or not you can attribute [it] to climate change I think remains to be seen. But I think certainly the climate modeling that I’m familiar with predicts a number of things. One is … more intense storms and more frequent storms. And also what we [will] see is increased variability in Great Lakes water levels.”

Fry agrees that, at least in theory, change in climate globally has the potential to deeply affect those who live around the Great Lakes.

“If you think just in the big picture, a warmer atmosphere can hold more liquid, and so we see more precipitation,” Fry said. “But I haven’t seen a specific attribution study to show that our higher lake levels at this point are a direct result of climate change. But just looking at the historical record, we’re certainly in an unprecedented time in that we’ve set new water level records and we’ve had record amounts of precipitation recently.”

Warming atmospheres affect the lakes in other ways too. In the winter, ice and snow serve as a natural form of shore protection, defending against erosion. Additionally, without an ice cover on the lakes, water evaporates into the cold air and then condenses, producing what is called lake-effect snow. Lake-effect snow is notorious for its ability to deposit copious amounts of snow in a short period of time, sometimes encasing lakeside buildings in snow.

“We didn’t have any ice cover this year,” Mackey said. “With the gradually warming temperatures that we’re seeing — climate-induced, I believe — we’re seeing a significant reduction in the amount of ice cover on the lakes, which increases a degree of evaporation, which helps actually expand that variability.”

Because of these higher levels of evaporation, in future years the Great Lake system could see record-low water levels — also as a result of climate change. These lows can dry out wetlands and threaten animal life. Lows can also impact commercial shipping in Ohio for dredging in naval channels.

Dredging comes with its own host of environmental consequences — the practice can kill small fish, the loss of which impacts the ecological balance of an entire water system. Dredging also releases harmful chemicals such as mercury and other heavy metals that have accumulated deep in sediments, and can further exacerbate shoreline erosion.

“With climate change, we do expect an enhancement of extremes,” Eveleth said. “So it might be that our envelope continues to increase and we get higher highs in water level and lower lows in water level as we go through those natural cycles.”

In addition to changes in water level, the Great Lakes face other threats. Invasive species, such as Asian carp, have damaged the health of native fish and other underwater creatures. Since 1800, over 25 species of invasive fish alone have entered the Lakes. But fish are only part of the problem: Zebra mussels and quagga mussels, known for reproducing and spreading rapidly, have detrimental effects on the lakes. The mussels suck the plankton out of the water, leaving most small fish with nothing to feed on and unraveling the base of the whole food web in the lake system.

Another concern for the lakes is the impact of agriculture. Fertilizers used on farms can leak into the waterways and run into the Great Lakes. These excess nutrients feed algae, causing a “bloom” in algal growth, much of which is bacteria.

“Those bacteria have toxins in them, and that can impact human health,” Eveleth said. “So when those toxins get into a drinking water supply, as they did in Toledo in 2014, the water plant has to shut down, and the town went without water for a short period of time.”

Mackey and his team are undertaking a variety of efforts to support property owners and others affected by changes in Lake Erie. They send coastal engineers to homes that are threatened by erosion to give individuals recommendations on how to protect their property. The team is working to get funding for homeowners to build shoreline protection infrastructure through a special improvement district.

“We’re trying to think outside the box, and we’re trying to be innovative and [come] up with new solutions to deal with this problem,” Mackey said.