Creating a 21st-Century Landscape in Oberlin

An image of the author’s property.

In December 2006, Mary and I decided to retire from our home in Troy, NY, where we had lived for 33 years — half our lifetimes. Our primary goal was to fulfill a long-held desire to replicate Hilltop, the home of our close friends David and Harriet Borton, that runs on sunshine. Trail Magic, our home in Oberlin, was inspired by the Bortons’ home to attain the same energy outcome. With our focus on making our home completely powered by solar energy, the landscape received minimal attention, aside from keeping water from entering the dwelling.

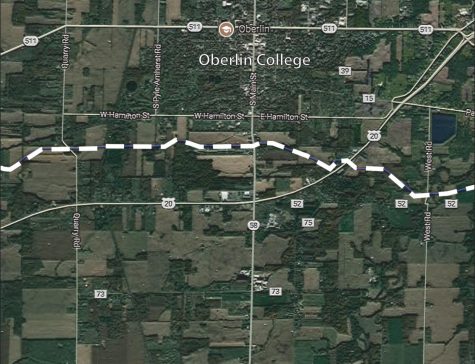

Our five acres, located on the south side of East College Street, slopes gently down to Plum Creek, a stream that flows through Oberlin and is our property’s southern boundary.

We dug a pond that would provide soil for raising the house site, thereby permitting access to the city sewer. We created two swales that ran down the east and west sides of the house, with the west-side swale putting water into the pond and the east-side swale flowing down to Plum Creek. “Swale” generally refers to a sunken or marshy area with gently sloping sides. The builder installed house footer drains on the south side of the pond.

When we acquired the property, it was about half meadow and half forest, and it harbored several dozen ash trees that were fated to succumb to the emerald ash borer that had not yet reached Oberlin; within a decade, there were almost no live ash trees in Northeast Ohio. The east side of the property, south of the house, was a meadow that ended in the Plum Creek floodplain, while on the other side there was a savanna prairie that ended in woods. A swale with invasive plants (multiflora rose and buckthorn that we’ve mostly removed from the property) was between the meadow and the savanna. A row of Osage orange trees in the swale extended south to a huge sugar maple just before a stand of 70-foot-tall mature ash trees. We cleared the swale except for Osage orange, maple, and black walnut trees and filled it with wood chips over several years. We then broadcasted tall grass prairie seeds and planted dogwood, American sycamore, white pine, and bare-root spruce plants. We put a four-foot fence around each plant to prevent deer from grazing on the young seedlings in the first years and then to keep bucks from girdling the young trees when they rub off antler felt in the fall.

We lumbered some 30 mature ash trees along with several mature red oaks and black walnuts to yield finished lumber that became beams, floors, shelves, counter tops and trim in the house and barn. We cut the treetops into firewood that we used, gave away, bartered, or sold.

We reforested the area below the pond with mostly native trees, including American sycamore, tamarack, dogwood, and river birch. As in the swale, we placed a fence around each bare-rooted seedling planted. We planted about 20 fenced trees — buckeye, dogwood, pawpaw, hawthorn, among others — in the front yard to create a wooded area that would require minimal mowing as the tree crowns grew to shade the yard. On the western side of the property above the pond, we made a 6,000-square-foot garden with an eight-foot-high fence to keep out deer.

Creating this garden was far more challenging than making a garden in Connecticut, Maryland, New Jersey, or upstate New York where we lived before, because the soil is fine glacial clay that has zero perk — that is, if you put water in a hole, it stays there. I discovered this issue our first spring in Oberlin when I planted broccoli plants next to the barn and they did not grow; they drowned. We purchased several dump truck loads of sand and leaf-mulch soil to rototill into the clay to start making garden soil.

Our first year, carrots were about two inches long — the depth of the soil above the native clay. Over the next six years, we mulched with grass cuttings from our meadow and savanna fields, and hauled with our Toyota pickup truck many loads of free leaf-mulch soil gathered from where the city dumped collected leaves. By 2012, the garden was 6,000 square feet and the soil about half a foot deep. In the best years it yielded enough food to feed two people for about three months.

Wes Jackson, co-founder of the Land Institute in Salina, KS, impressed me with the productivity of the tall grass prairies that made 12-foot-deep Iowa soil among the best agricultural soil in the world. We purchased a mix of tallgrass prairie seeds and planted an area in the backyard that, after nine years, has matured into a tallgrass prairie. Tall prairie grasses — big bluestem, switchgrass, and Indiangrass — put roots that sequester carbon six feet into the ground. Some 65 percent of the carbon they fix goes into the soil. When the prairie matures and its roots go deeper in the soil, the prairie absorbs more and more water.

Thirty years ago, the goal for managing water was to get it onto your neighbor’s property as quickly as possible. Today, the goal is to keep all precipitation on your property. In order to achieve this goal, we designed our property to keep rainwater; our backyard tallgrass prairie was the first step. The second step was to fill in a trench in the bank of Plum Creek that allowed water from our land to flow into the creek. We had a dam constructed across the trench with an overflow pipe that would keep water on our property without putting water onto neighboring properties.

The forested areas of the landscape provide us with the annual cord of wood we use to heat Trail Magic. However, wood heating can produce pollutants unless done properly. Well-seasoned hardwoods should be burned and the stack temperature should be between 500 and 900 degrees Fahrenheit. We have heated with wood for 12 years, and our chimney and cap have no buildup of creosote, a harmful chemical that can sometimes result from burning wood. Some smoke is visible when lighting the fire, but the pollution is minimal. Beyond providing firewood, food, and sequestering carbon, our landscape provides habitat for myriad insects, small mammals, and food for a number of bird species, especially in the tallgrass prairie.

It should be noted that the house was designed for passive solar heating and lighting. Even on cloudy days, one can read in the living-dining room, bedrooms, and kitchen without turning on a light. Even if all lights in the house were turned on, less than 50 watts would flow, meaning in an hour only 0.05 kilowatt-hours would be used. The average two-person house in Northeastern Ohio annually uses about 2,800 kilowatt-hours for inside lighting, while we use less than 50 kilowatt-hours annually.

In summary, a landscape can reduce flooding; sequester carbon; provide food and energy (firewood); enhance biodiversity with its habitats and microclimates; allow for recreation, entertainment and education; promote health with the exercise its maintenance requires; and deliver aesthetic satisfaction by its inherent beauty.