In UCC Report, Northeast Ohio Identified As “Hot Spot” of Environmental Injustice

This past February, the United Church of Christ published a report on polluting facilities located in or near residential communities across the country. The report, titled “Breath to the People: Sacred Air and Toxic Pollution,” focused on 100 “super polluters” throughout the United States, and especially on the impact of those facilities on children under the age of five living in their vicinity.

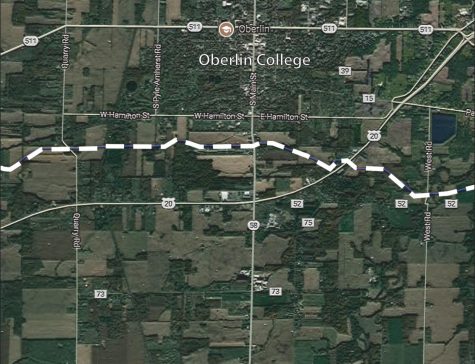

The report was primarily authored by Rev. Traci Blackmon, UCC associate general minister, and Rev. Brooks Berndt, UCC minister of environmental justice. In assembling the report’s narrative, the authors chose to focus on three “hot spots” of toxic air emissions: the Houston metropolitan area, Louisiana’s Cancer Alley, and the southeast coast of Lake Erie, including Cuyahoga and Lorain Counties.

For those not from Northeast Ohio, its inclusion on the list may come as a surprise, especially alongside a region like Cancer Alley, made notorious in environmental justice literature because of sustained exploitation by the petrochemical industry.

“Yet, it is not only the children in these well-known areas of toxic danger who command attention in this report,” Blackmon and Berndt wrote in the introduction. “Some of the facilities in the report’s Toxic 100 list have a seemingly inconspicuous existence. They hide in plain sight and threaten children in communities across the country.”

With a decades-long history in the environmental justice movement, the UCC has significantly advanced the study of practices enabling the disproportionate siting of polluting facilities within marginalized communities, as well as the devastating public health consequences of environmental racism. In 1987, the UCC’s Commission for Racial Justice published the landmark “Toxic Wastes and Race in the United States,” which found that race was the most important determining factor in where toxic industrial facilities are sited.

Then, in 1991, that same commission organized the First National People of Color Environmental Leadership Summit. The summit brought together hundreds of environmental leaders of color, who together drafted and adopted the 17 Principles of Environmental Justice, which continue to be heavily referenced in environmental justice literature today.

All of this is to say that Northeast Ohio’s inclusion in the report is especially noteworthy given UCC’s long and sustained history of environmental activism, and places the region in the context of ongoing battles against environmental injustice.

In its Northeast Ohio section, the report discusses MPC Plating Inc, which is located in Cleveland’s Hough neighborhood and produces fabricated metals. The plant is responsible for high levels of air pollution, including many toxins that are carcinogenic.

According to the report, more than 7,000 people live within a mile of MPC, 91 percent of who are people of color — a much higher percentage than the overall population. Further, 71 percent of the people living within a mile of the facility are low-income.

And MPC is just the third most noxious industrial facility in the region when ranked by toxicity-weighted tons of reported annual air pollution. The BASF Corp. facility in Lorain County emits about five times as much toxicity-weighted tons of air pollution, with approximately 200 more people living within a mile of the facility. While the environmental injustice narrative is a little less extreme than in the Hough neighborhood — 23 percent of individuals living within a mile of the BASF Corp. facility are people of color, compared to 91 percent — this figure still exceeds state population averages.

Other dynamics persist in the region as well. Earlier this year, residents in the city of Lorain — just up the road from Oberlin — filed a $41 million lawsuit, alleging that customers had been overcharged for water and sewer services for years. Petitioners further argued that the overcharging had led to water shutoffs, leaving low-income residents unable to meet their basic needs.

Water shutoffs are a well-documented issue across the Midwest; the past couple years have seen national outrage about the practice in both Chicago and Detroit, for example. It’s not as frequently, however, that you hear about these environmental challenges more commonly associated with urban environments discussed in a more rural context.

The UCC report, as well as Lorain’s developing water story — certainly only more pressing in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic — serve as important reminders that narratives of environmental injustice. These narratives, which too often break along lines of race, class, and ability, exist in our own backyard and demand pressing attention.

The coming years of climate change will drastically redefine environmental interactions in communities across the country and the world. As those with a commitment to sustainability and justice meet these challenges head-on, we will need to ensure that the needs of all communities are addressed, including those like Lorain County that sometimes escape the view of larger environmental narratives.