The Privilege of Community

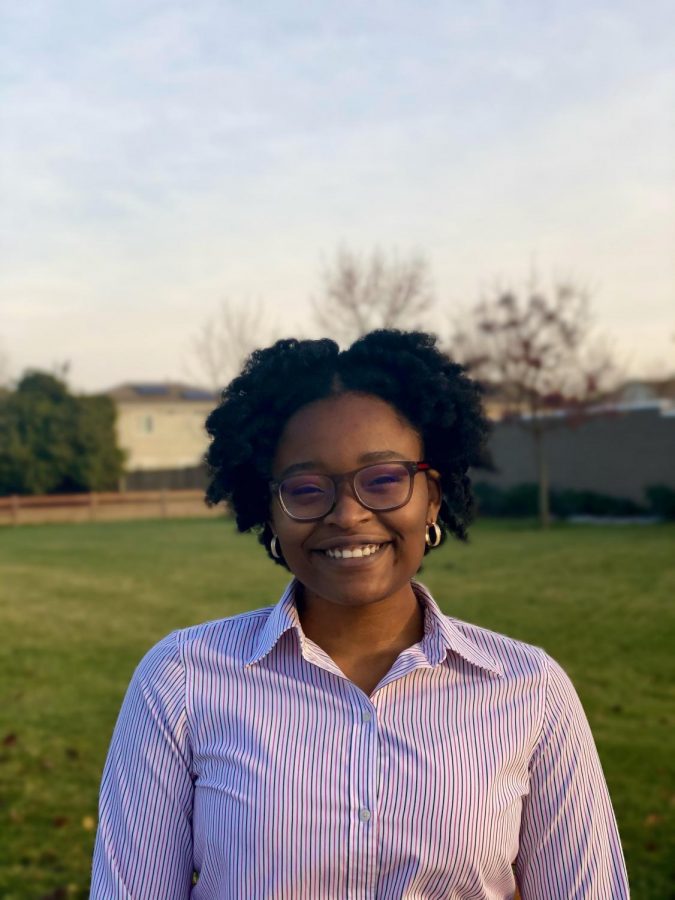

The mellow sound of the night’s lo-fi playlist echoes through the room. It’s kind of repetitive, but anything beats the deafening silence of Wilder 112. I look up at the four Brown faces surrounding me, brows furrowed in distress and a bit of anger as we head past hour three on the week’s sapling homework. We’ve only done five questions. The phrase, “What does this even mean?” has become the statement of the semester.

During the fall semester, I spent most of my time in the windowless study rooms of the Burton Hall basement. With both the Science Center and Mudd Center closed, there weren’t a lot of options. If we were lucky, we’d get the room that offered a glimpse of some natural light, and along with it, a show of the different shoes people wore as they walked along the side of the building. But the two Black women I worked with during this time made the experience of taking four STEM courses less daunting.

The majority of my experience in Oberlin’s STEM community has been filled with moments like these, both with Black and non-Black students. Principles of Organic Chemistry leaves you with no other choice than to build community. For the most part, my experience has been a positive one. There were occasional times when I did feel alone, despite the 35 other students surrounding me or, in some cases, the six students who bothered to keep their cameras on. When I reflect on times like those, I realize the importance of having a community standing beside you.

I’m not a person who can say that I’ve always felt drawn to the sciences; in college I got a late start. As a result, I found myself trying to get involved in the Biology and Chemistry and Biochemistry departments to make up for lost time. Before the fall 2020 semester, I decided my newest endeavor would be research. The following semester, I began working on a research project with Associate Professor of Chemistry and Biochemistry Jason Belitsky, which I am continuing this semester. Our research surrounds catechol-based coatings that change color when they bind with different metal ions such as lead. These could potentially act as sensors for metals in water. We are still trying to create a streamlined system to build an understanding of the chemical composition of the materials.

My past two years in the STEM field have taught me a lot. Along with a wide array of new lab techniques, I’ve finally learned how to succeed in these courses. The trick is to find a community to go through the class with. But the thing is, your experience in the STEM field at Oberlin might be based purely on luck. I’ve been fortunate enough to have always had peers who shared a similar identity with me in these courses. But I know others haven’t been as fortunate.

Oberlin has made a somewhat admirable effort to provide Black students with the resources and spaces they need to succeed. Yet, progress such as the creation of the Roots in STEM Living Learning Community, one meant for underrepresented minorities in STEM, can be overshadowed by the addition of non-people of color and non-STEM students. As a result of such mistakes, the responsibility is often placed on Black students to create and defend their own spaces. So, as students try to navigate this field on their own, it’s all about luck.