Juneteenth in Oberlin: Looking Back and Moving Forward

I began my first Oberlin Juneteenth in Tappan Square with a game of Jack in the Bush with Ms. Jessie Reed, a long-time resident of Oberlin who has lived in town since 1960. She learned how to play this game from her father, Major Holley. The goal of the game is to accumulate the most peanuts to become the “Champ.” Although the origins of Jack in the Bush are widely unknown, she hypothesizes that it was born from fugitive slaves hiding in the bush as they were escaping slavery.

“Jack in the bush,” Ms. Jessie Reed said to me. “Cut ‘m down,” I responded. “About how many?” She asked. “Seven.” She smiled, gave the peanuts in her hand one more shake, and revealed eight peanuts on the table between us. I handed her one peanut and we kept playing, switching roles each round.

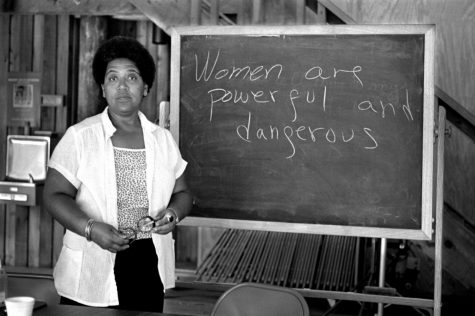

Professor Emeritus Adenike Sharpley served as co-chair along with Thelma Quinn Smith and Frances Walker to organize the first Juneteenth festivities in Oberlin in 1995. The theme in ’95 was “Family Reunion.” There were over 1,500 people in attendance. “It is hard to find information about Juneteenth,” Steve Hammond wrote in the Oberlin News-Tribune, June 25, 1995. “It doesn’t get a listing in the Encyclopedia Britannica, nor can you even find the word in Merriam-Webster’s [Dictionary]. That, in itself shows how important it is that we have revived Juneteenth celebrations in Oberlin.”

The City of Oberlin officially recognized the holiday in 2004, after the City Council passed a resolution that resulted in an event name change from Oberlin Heritage Days to the Oberlin Juneteenth Celebration Festival. However, it took a few years for the City Council to embrace the holiday. The council was concerned that white Oberlin residents would feel uncomfortable celebrating a a holiday that commemorates the liberation of formerly enslaved Black people. In an article for the News-Tribune, Phyllis Yarber Hogan shared her support for Afrocentric Oberlin events and ended the article asking, “If Oberlin’s Black and white populations cannot come together to celebrate one of the stellar events in Oberlin’s history, how can we expect to move forward?”

Twenty-five years later, Juneteenth can now be found in the Merriam-Webster dictionary and the Encyclopedia Britannica. And on June 16, 2021, it was declared a federal holiday.

We stopped by the Black owned businesses: Gee Gee’s Kettle Korn stand, purchasing incense from Ms. Ade, and winter berry cream from Touched by Grace. Next, I boarded the trolley to the Juneteenth Bluesfest at Lakeview Park in Lorain. We made a stop in Elyria to pick up the first elected African American and Independent Mayor of Elyria, Frank Whitfield. At Bluesfest, I enjoyed performances from the New Orleans-style second line with Da Land Brass Band and Audacity For Sale. I had my first Polish Boy sandwich from Uncle Mike’s Catering and the best banana pudding I have ever tasted. In between musical performances, Mayor Whitfield and Mayor Jack Bradley of Lorain addressed the crowd. Mayor Whitfield expressed his desire to make future Juneteenth celebrations a countywide event, to knock down the barriers between Oberlin, Elyria, and Lorain.

I took the trolley back to Oberlin and attended the Maafa Memorial Service in Westwood Cemetery. Maafa is a Kiswahili word that means “terrible occurrence” or “great disaster.” The ceremony is a national movement that commemorates the loss of life of Africans in the transatlantic slave trade. The ceremony began with a Yoruba libation and a performance by Daniel Spearman. Then, those in attendance were asked to recognize the United States Colored Troops who served in the Civil War who are buried in Westwood Cemetery. After singing the Black national anthem, “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” Black elders in the community put white candles on the memorial of Lee Howard Dobbins, a young fugitive slave who passed away from sickness in Oberlin in 1853.

We then listened to Margaret Christian’s speech, “Claiming the Unclaimed” — one of the most resonating moments of my Juneteenth. She preached the importance of preserving our histories and told her own story as well as the story of Marie DeFrance, 1874–1926, and her daughter, Mary Elizabeth DeFrance. They purchased the millinery at 31 West College Street and owned that business for over 30 years. Marie DeFrance was born in New Orleans but grew up in Oberlin. She was baptized at Christ Episocopal Church, attended Oberlin schools, and studied at Oberlin Conservatory for a year. I could hear the passion in Ms. Christian’s voice as she spoke of how much Oberlin has changed; there was a longing in her voice for a time when she felt true community here.

Ms. Christian asked the small crowd to look around us and see how many College students and faculty were in attendance. There were not many. In fact, the entire day I wondered when more Oberlin students would show up to all of the activities planned that weekend. As an institution that loves to tout our history on every admissions tour and talk about how the town and College of Oberlin were founded together, this disconnect was frustrating to witness. Ms. Christian ended her speech by asking us to think of our loved ones as we sprinkled flower petals on Marie and Mary Elizabeth’s graves. When it was my turn, I thought of my late grandmother, Alice Samuels Jones, and my high school mentor, Brittany Noelle Chase. Both women have helped me along my path and are instrumental to my own history.

As I look back on my first Juneteenth, I had to remind myself that it was the first large event I have gone to since COVID-19 shut down everything in March 2020. We are all currently experiencing a collective moment of transition. We must ask ourselves, “What histories are we going to tell and remember from a year where we suffered such an enormous loss? How are we going to learn and grow as a community, country, and world, and continue to fight for Black liberation?”