A Conversation with Johnny Coleman

Johnny Coleman has been a professor of Studio Art and Africana Studies at Oberlin College for the past 28 years. He is an artist who specializes in the mediums of sound, sculpture, and space. His Oberlin course offerings include Blues Aesthetic, Talking Book, and Something from Something, and cover the skills of woodworking and storytelling. He is one of my favorite teachers, and this Juneteenth, I borrowed some of his studio time to talk about his current and past works, as well as his many inspirations and aspirations. His work, an alter titled “A Landscape Convinced: For Nyima” is featured on the back cover of this issue.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

What drew you to Oberlin?

To be honest with you, I didn’t trust Oberlin. I didn’t. There’s too much talk about the Underground Railroad.

You took that as a red flag?

I didn’t trust it. I ain’t see enough Black people talking about the Underground Railroad.

It seemed like maybe this was performative. But my then-wife applied, and she came and told them her husband was also an artist. She called me and was like, “They’d like to see your work.” Long story short, they offered us both a position. So I said, “Okay I’ll come for two years, then I’m getting the fuck out of Dodge.” And I got out here, and at my interview, in fact before I came, I let the Art department know I was interested in interviewing the Black faculty. And I got snowed in, and I could not leave. There was a blizzard that blew in behind me. So I came in on Friday, and Ms. Ade, [Assistant Professor of Dance], kept me at the [Afrikan Heritage] House until 11; Black students had come to my talk. And the chair of the Art department lived across the street from the House. There was no room at the inn, so I’m sleeping on the couch in her living room. They walked me across the street at 11, and I’m snowed in for the next three days. Saturday morning, James and Mildred Milette met me in a blizzard for breakfast, and we’ve been in love since then.

This was no surprise to me. After-hours in Afrikan Heritage House are bound to make anyone fall in love with Oberlin. But I did appreciate Johnny’s candor and perception of the College. Many of us were not so intuitive as to see the mirrors behind the smoke.

What else did you notice in your introduction to Oberlin?

There was nothing about admitting Edmonia Lewis. Nothing. Ain’t nobody even mention her name. So, the first mention of Edmonia Lewis in the Art department — at least in the time while I was here — was in Blues Aesthetic. Blues Aesthetic happened because Black students came to me my very first semester here. They came and were like “Johnny, will you teach a class on Black art?” “Hell no! I’m in the studio, and I’m teaching my classes, and I’m getting the hell out of here! Y’all know I’m not an art historian.” But they didn’t take no for an answer.

I’m glad they didn’t.

They kept coming in, and I kept saying no. Then finally this one sister from Cleveland got her hands on her hips and said, “Then why are you here?” [laughs] Beautiful sister.

So, my first spring here, Blues Aesthetic was started, and I’ve taught it for 28 years. Only when I’m on sabbatical has it not been taught.

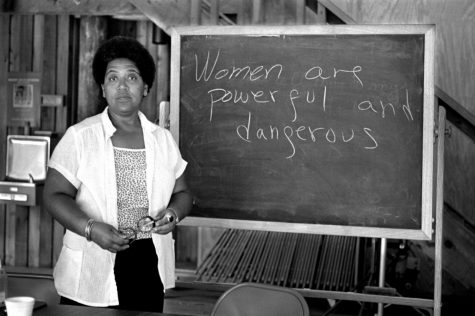

In thinking about constructing the memorial for Toni Morrison, and also the work you’re doing with the women who came through Oberlin, you’re archiving Black women’s stories and helping them share their narratives. How do you position that within your work? Is it something you think about consciously or is it just who you are?

I think about it consciously, but I wouldn’t exist except for Francis Wilma McCoy — my mom. And my mom would never call herself a feminist, ever, ya know? Feminists, when that stuff came out it didn’t involve Black women. Not at all. I was a little boy reading Maya Angelou, and my mother took me to see her. I saw her with my family a couple of times, and I saw James Baldwin with my family a couple of times. But then I took my mom to see Maya Angelou when I was an adult, and we got to sit and talk with her. We can’t talk about Black people without talking about Black women. Period. My work is about my relationship to my culture, and my culture is related to people, so that’s what I work with.

When [my son], Iyo, was four, Toni Morrison asked me to compose a piece in response to Beloved. This is 1995. The first time I read Beloved was in ’89 or ’90. I read it a couple of times, and I thought it was a masterpiece. So I read it again, and at this time I had a child — I had a son and a daughter — and it made all the difference in the world. I did two pieces, one for Paul D. and one for Sethe. I brought them both. She took both of those pieces.

I grew up reading Maya Angelou, and — you’re not gonna believe me — but I grew up reading Angela Davis’ talks. She was young, really young. So we had at home, not only Ebony and Jet that every Black family had, but we also had the newspaper that the [Black] Panthers put out. My parents made sure my brother and I both read. And I’m dyslexic. I could read before I went to school, and my brother was younger than I was. I grew up with two parents who realized that their kids were growing up at a really critical moment in American history.

Toni Morrison is a giant, and she had that insight into Black culture, and she just meant everything to me. You read her statement about what her work is, “Site of Memory”: I wanna imagine the interior lives of my ancestors. That means everything to me. She will always be a foundational figure for me. John Coltrane will always be a foundational figure for me.

Black people couldn’t exist without both of us — both of those energies. So it’s not a conscious thing to tell Black women’s stories; it’s a conscious thing to explore Blackness, and you can’t do that without Black women. Period.

How would you describe your work to someone who’s never encountered it before?

It’s a story; I’m a storyteller. Mostly, I work with sound; I work with spoken [word]. That’s what I do. But, if I’m using physical material, I’m using material that I see as alive and sentient — material that can witness.

Like instruments?

Yeah, absolutely! Language is an instrument; it carries the story. If I were to describe my work, I would say, “I’m invested in keeping the story alive,” but all I’m doing is paraphrasing August Wilson. Ya already know: tell the story; tell it now; tell it in a manner so that others will tell the story. That’s how it stays alive. If a part of our history has been eliminated, we are not complete until we have done everything we can to bring it forward.

This is exactly what Johnny’s most recent work is centered on: recovering lost stories. He has set out on a nearly 20-year journey to uncover the names and stories of eight escaped African American women who accompanied Lee Howard Dobbins on his journey north. He was left here, in Oberlin, where he soon died from illness in 1853. All we know is that these eight women continued on their journey north to Canada. The exhibit is now available for viewing at Transformer Station in Cleveland. You can check out Johnny’s previous work on his website peasandricepress.com.

Are there any last words you can share with us?

The Blues is everything for human beings. The story is everything, and the Blues is our story. I was taught to make sure you water your garden and hold the door open. So that’s what I’ve been doing.