Oberlin’s History Not As Gender-Inclusive as You Might Think

1951 Hi-Oh-Hi Oberlin yearbook

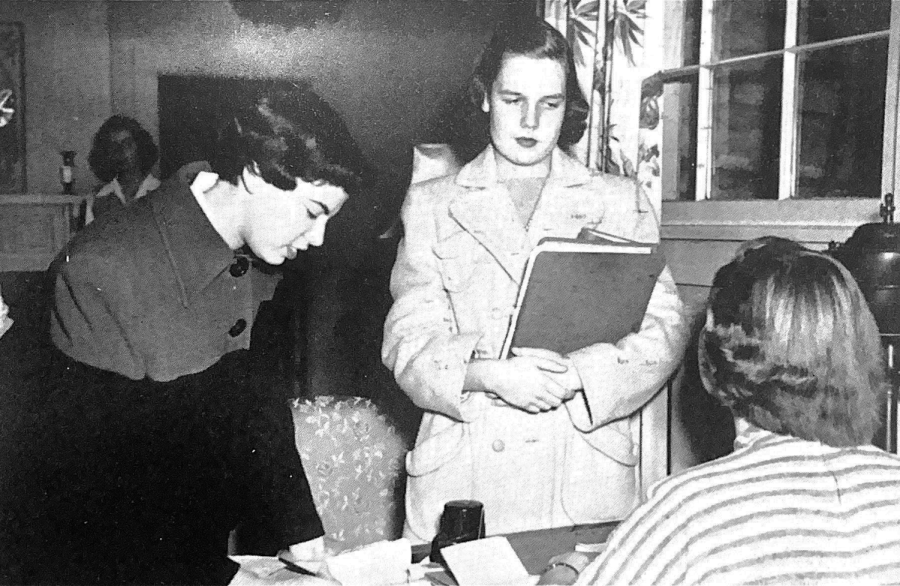

Peggy Koye looks up from her books as Mary Laub performs the chore of signing out at Webster’s bell desk for the evening.

This year, Homecoming coincided with Oberlin College’s reunion for the classes of 1961, ’62, and ’63. I initially went to the Homecoming football game to say I had gone, but I ended up staying a lot longer than I had planned, though it wasn’t because I was holding out hope for an Oberlin win. The man sitting in front of me was a class of ’62 alum with an insight into Oberlin’s history previously unknown to me. Amidst cheering, gasping, and booing, he began to tell me about the differences he had noticed since being back on campus. One of the most memorable things he mentioned was the 10 p.m. women-only curfew that was in place during his time at Oberlin, jokingly remarking that once the women went home, the men didn’t have much of a reason to be out anyways.

When I toured Oberlin in 2021, my tour guide boasted of gender-neutral bathrooms, a lack of Greek life, and the fact that Oberlin College is the oldest coeducational liberal arts college in the United States as markers of the institution’s radical inclusivity. Learning about a women-only curfew being in place as late as the 1970s shook my perception of the College. I couldn’t understand how an institution with a reputation such as ours could support rules that were so obviously oppressive to women during a time of mass social advocacy for women’s rights.

At Oberlin College, 1966 was a year characterized by fierce student advocacy. For years, the student body protested the women-only curfew and the strict open-door policies implemented in public student meeting spaces aimed at preventing male and female students from entering into relationships. The student body was in agreement that these rules undermined student autonomy and that the constant supervision by the administration inhibited a cohesive living and learning community. The Sept. 20, 1966 issue of The Oberlin Review discussed the beginning stages of a transition away from Wilder Hall parlor monitors and mandatory open-door policies. However, these discussions were not based on the administration’s desire to provide students with more autonomy and freedom but rather were influenced by a monetary incentive. The Dean of Students at the time, Bernard Adams, stated that the College’s reasoning for not hiring parlor monitors for the coming semester was that “the money could be put to better use elsewhere.”

Published in that same edition of the Review was an editorial written by the Editorial Board. The article expresses discontent with Wilder parlor “dating rules,” and voices a very legitimate fear that discussions about these outdated rules will “go on for months, thereby preventing a direct confrontation between what students want and what the Student Life Committee might not want to give them.” The editorial concludes with fighting words that aptly illustrate the student body’s fatigue with a domineering administration resistant to change: “if there is going to be a fight, let’s cut out the philosophy and have it already.”

The disconnect between Oberlin’s reputation and its practices is apparent nowhere more than in the historical record left by the Review in the late fall of 1966.

On the front page of the Nov. 1, 1966 issue of the Review is an article that discusses the United States’ recognition of Oberlin College as a national historic landmark — being the first college in the United States to admit women. At the same time, signs of a continuing debate shone through the Review’s coverage, such as in a news brief included at the end of the previous issue, published just three days before on Oct. 28. The brief covers the concessions made by both Student Senate and the Faculty Committee on Student Life, in which Student Senate had to reject a SLC proposal that “parents of sophomores be given the opportunity to ask that their daughters not have unlimited hours.” In this way, the College faces a strange dichotomy of culture, on the one hand being praised for its inclusive reputation, and on the other, facing an internal pressure to restrict the agency of its female students. History like this shows that, even within an institution that makes strides toward progressive policy, the truth of its morals and customs can be much more complicated.

College administrations are similar to federal governments, and not just in that college students love to complain about them. As the governing institution of the student body, a college administration must reflect the sentiments of the students. The only way to do that is by listening, not just by providing a platform for students. Having a nominally powerful Student Senate that is given the opportunity to communicate with administration is little more than a performative act by the administration if the exchange does not lead to policy change that helps close the gap between student values and the rules they must adhere to. If this does not occur, students are given a soapbox placed in front of a brick wall.

Oberlin’s progressive reputation is well deserved and something to be proud of, but we must be clear about who we credit for this reputation: Oberlin is progressive because its student body is progressive. Even considering that the regulations at Oberlin were not excessively oppressive by 1960s standards, the issue lies in the dissonance between the political attitudes of its student body and the administration that represents them.

Even if it feels like the administration’s attitude will never truly reflect the sentiments of the students, students should not throw in the towel on consistent advocacy for better living and learning conditions. The fact that the administration has been willing to change policy for the purpose of quieting the student body, even if its motives were disingenuous, shows that volume still leads to change.