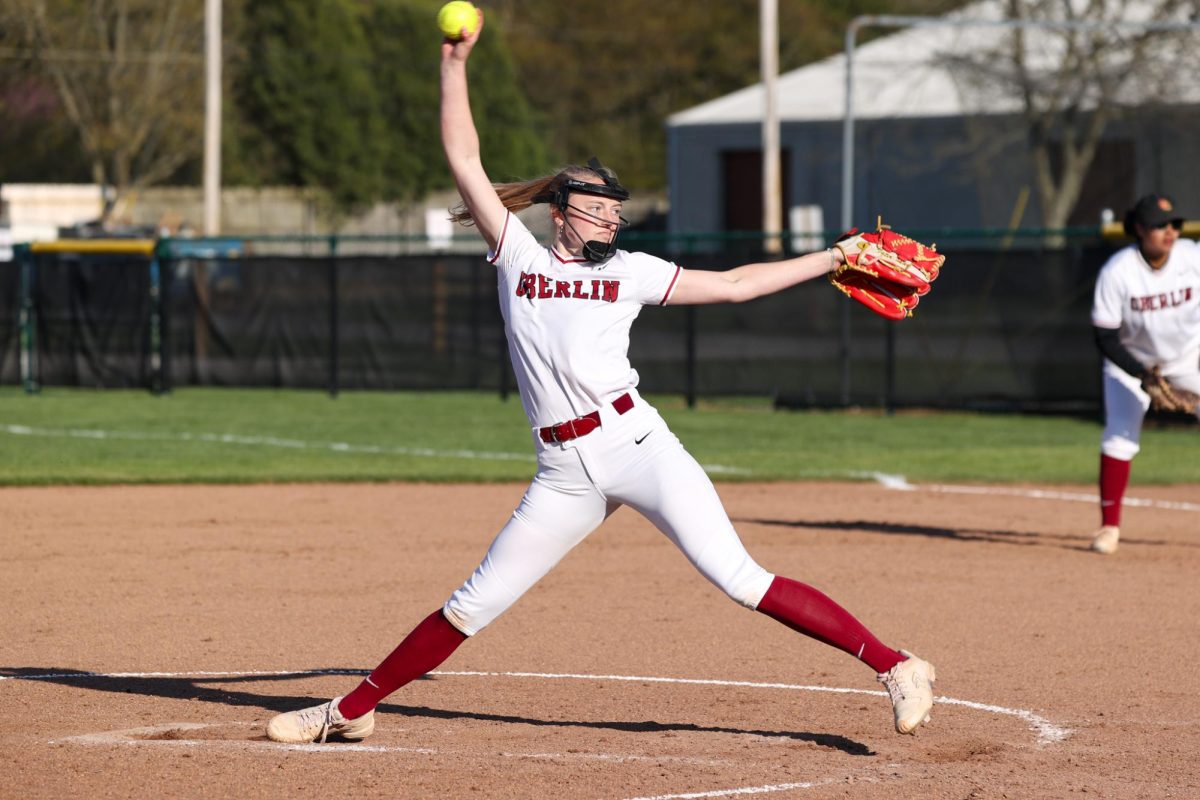

Iphigenia at Aulis [Mee remix]: An Oberlin-Cleveland Collaboration

April 20, 2012

Fact: Euripides wrote Iphigenia at Aulis over 2000 years ago.

Fact: The production of Iphigenia 2.0 currently featured at the Cleveland Public Theater (CPT) from April 12-28 includes soldiers clad in mere underwear dancing to hip-hop, references to “Palestinians … with RPGs” and an absolute absence of togas. Which is not to call it a politically motivated strip show. The production is far too beautifully nuanced to necessitate a stack of singles.

Iphigenia 2.0 is the first major production to come out of a new relationship between CPT and Oberlin College. This time around, CPT gave 13 student actors and two student stage managers the opportunity to work on and around a professional stage with working actors. Plans have been set in place to continue the partnership, and the next collaboration will take the form of an endeavor called Oberlin ArtS Intensive Semester in which a group of Oberlin students will work with staff at the CPT to create a devised theater piece expected to go up next February. Director Matthew Wright also intimates that the relationship will continue to flourish, stating, “I’m hopeful we can do some kind of production [with CPT] at least every other year.”

Written by Charles Mee, Iphigenia 2.0 is very much a remix — a mashing-up of the ancient, modern and timeless. The plot is fairly straightforward — Agamemnon (Tom Woodward), a politician type, desires to send his soldiers to war. His soldiers, in an act of defiance unimaginable in our day and age, require him to sacrifice something of his own before expecting them to put their own safety at risk — the life of his daughter, Iphigenia (College senior Marina Shay). Agamemnon tricks Iphigenia into visiting the army’s disembarkation point on the pretext that she is to marry a soldier named Achilles before the army departs.

Everyone’s life goes downhill from there.

Director Wright and the cast and crew, while remaining, to a large extent, true to the text, put their own spin on the play — Mee encourages the public to “pillage [his] plays as [he has] pillaged the structures and contents of the plays of Euripides and Brecht and stuff out of Soap Opera Digest and the evening news and the internet.” Among other modifications, Wright expanded what he called some “little numbers” in the text, increased the number of soldiers and bridesmaids (which allowed for intricately choreographed, visually arresting dance sequences) and played around with a character listed in the program as “A Veteran” (College senior Andrew Gombas).

Woodward’s Agamemnon is one of the few male characters not portrayed as hyper-masculine, which, surprisingly, encourages the audience to empathize with his soldiers. Disregarding for a moment the questionable moral implications of the soldiers’ demand for sacrifice, Agamemnon’s portrayal as a “modern politician” unaccustomed to getting his hands dirty — a soft ‘suit’ in a world dominated by testosterone — seems like a deliberate slap to the face of his troops. Small wonder that they compel a “sense of commitment from their leader[],” as a line from the play reads.

The production presents many arresting performances — Menelaus (Nicholas Sweeney), marked by the horrors of war; stiletto-ed Clytemnestra (Heather Anderson Boll), desperately tangoing to seduce her daughter’s faux-fiancé, Achilles (College senior Aaron Profumo), in a last-ditch effort to save her daughter’s life. Despite the strong acting and the awe-inspiring, physically demanding, synchronized dance sequences by both the bridesmaids and soldiers, the most memorable was from Gombas’s portrayal of the Veteran. The image of a wounded, smirking, masked veteran of Vietnam or the Gulf War wandering through what playwright Charles Mee describes as “a big party riot murder war” burned itself into the minds of the audience. Gombas’s Veteran was a figure intensely at odds with the anarchy surrounding him — arguably the one person maintaining any sort of awareness in a sea of chaos. It was, simply put, very cool.

The main problem with this production lies in the text, not with any given actor. When — spoiler alert! — Iphigenia sacrifices herself for the common good, she says, in an unexpected display of pragmatic thought, “To save one life / you would put a thousand others in jeopardy? / You and I both know / this would be wrong.” Though Shay’s rendition of Iphigenia’s new selflessness was itself commendable, the arc of her character as set out by Mee was jarring. Given her deliciously obnoxious entrance, Iphigenia’s sudden selflessness and willingness to sacrifice herself for the survival of others appears strikingly, even implausibly, out of character. Infuriatingly, Mee leaves the justification of her change of heart to audience guesswork.