Title IX Legislation Has Protected Student Access to Education for 50 Years

Photo courtesy of Oberlin College

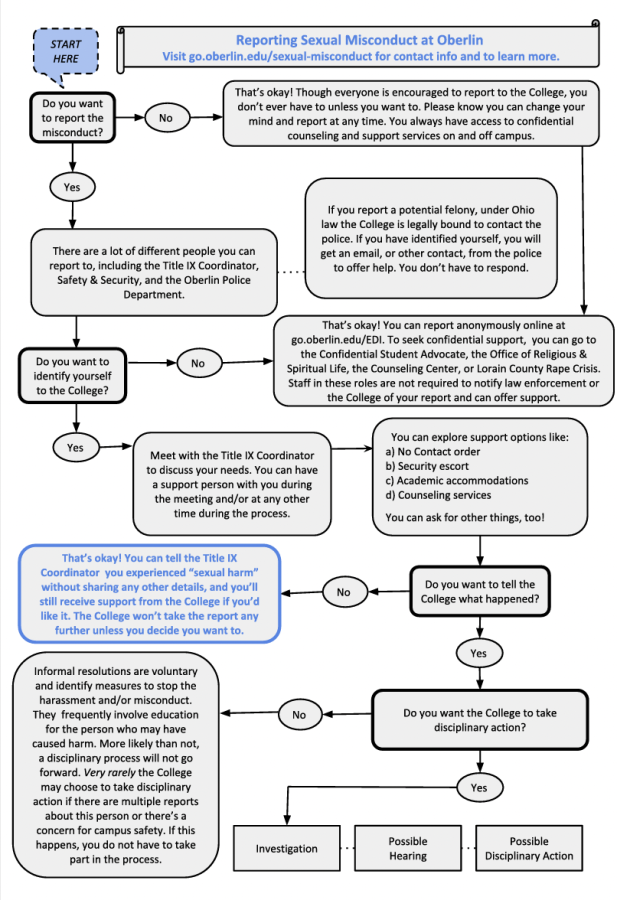

At Oberlin College, Title IX processes can include an Adaptive Resolution Process, a Formal Resolution Process, or neither.

June 23 of this year marked the 50th anniversary of the passage of the Education Amendments of 1972, which includes a provision known as Title IX. On Dec. 5, Survivors of Sexual Harm and Allies hosted an information session about the legislation. At this session, SOSHA invited guests from firm Marsh Law and Leda Health, an organization centered around supporting survivors of sexual harm, to speak to attendees.

Associate at Marsh Law’s Pittsburgh office Amy Mathieu, who represents Title IX claimants and survivors of sexual abuse, was one of the speakers at this event. According to Mathieu, Title IX has evolved over time to provide opportunities for survivors of sexual harm to achieve justice in various capacities.

“The brief overview is that it provides that men and women have equal access to education,” Mathieu said. “But it provides more paths and methods for female students to gain better access to education through bringing complaints forward when something happens on campus that then, in effect, blocks their access to education. So if they have to sit in a classroom next to their assaulter, they’re not going to have full access to education. That’s how it’s been interpreted over the years to provide more avenues to justice for students.”

This presentation was one of multiple events staged this past semester in commemoration of the Education Amendments. More commemorative events are slated to occur next semester according to Director for Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion and Title IX Coordinator Rebecca Mosely.

“I do know that there are some groups that are really looking at things like the Dobbs decision and thinking about how that kind of connects in … all of this,” Mosely said. “There’s some discussion right now about that for the spring. I think there’s a lot of work happening on campus around this.”

Additionally, Mosely expects SOSHA to continue its Title IX-related programming with events similar to that which occurred Monday. She believes this type of student-run programming around the legislation exemplifies what makes Title IX at Oberlin unique.

“I think one of the things that makes it really unique here at Oberlin is the passion that our students have for making sure that consent education is happening and making sure that folks are being held accountable for it,” Mosely said. “The other thing I would say is unique to Oberlin is [that] Oberlin has, in my experience, always been on the front edge of how things are done in best practices.”

Earlier this semester, in conjunction with the Homecoming football game, the Athletics Department created a document exploring the history of Title IX at Oberlin titled “Title IX Across the Decades: Stories of Our Past That Pushed Us Forward.”

“It’s important to understand that before 1972, women were not just discouraged from playing on the same field as men, they were not permitted,” the document reads. “In basketball, women were limited to half-court play and restricted to three dribbles. Even here at Oberlin, the women’s team never had a uniform and often played in their own ‘cut-off jeans and any white blouse’ (Jane Littmann ’72). More often than not, games were cut short because ‘it was time for the men’s team to practice’ (Jane Littmann ’72).”

The document includes photographs and texts divided into several sections, including “Life Before Legislation” and sections highlighting female student-athletes throughout campus history. Due to its original interpretation, Title IX is rooted in sports equality on campuses despite its broader implications today.

“I would say that it started out very geared toward spending on sports and giving women access to educational programs through academics and extracurriculars,” Mathieu said. “It’s obviously transformed into a huge protection for women on campus.”

Today at Oberlin, Title IX can be used in a variety of ways. In particular, survivors of sexual harm, harassment, or discriminatory practices can use the legislation to achieve various routes to justice.

“So the first thing that happens when somebody files a report with my office is that they receive an email from me just saying, ‘Hey, here’s information for you. You’re welcome to meet with me or not,’” Mosely said. “Once that happens, if the person does choose to meet with me, the next step would be to talk through what it is that feels most supportive to them in terms of a process.”

These avenues of support can take various forms. Individuals who file reports can choose to go no further than the report itself. However, if they choose to engage in a further process, there are two different options: an adaptive resolution process and a formal resolution process. While the formal resolution might entail bringing the case before a hearing panel, the adaptive resolution does not.

“The Adaptive Resolution Process is a series of inclusive conflict resolution practices that yield participant-authored, effective, and just outcomes through examination of attitudes and behaviors that contributed to the conflict or harm; and that result in clear accountability measures that repair harm and discourage future harm,” the College’s Adaptive Resolution Process Procedures reads. “Adaptive dispute resolution practices — including conflict coaching, facilitated dialogue, mediation, and restorative practices — are available to participants on a voluntary basis. ARP is an alternative to the formal resolution process and does not result in College-mandated disciplinary action against the responding party. The College, however, will enforce any signed resolution agreement.”

By contrast, the formal resolution process “is designed to provide fundamental fairness and respect for all parties by ensuring adequate notice, an equitable opportunity to be heard, and an equitable opportunity to respond to a report under this policy,” the College’s Formal Resolution Process reads. “The FRP applies to complaints of violations of the Title IX Sexual Misconduct Policy, the Nondiscrimination and Harassment Policy, and the Prohibited Relationships Policy and consists of three phases — the investigation, the hearing and the appeals.”

According to Mosely, both processes are designed to support the survivor.

“It’s up to each individual what feels like the right process to take to resolve what happened,” Mosely said. “My job is really just to make sure they have the information, and [to] support them in whatever that choice is that they make at the end of the process, and then [to] help follow that process through to its end, whatever that means.”