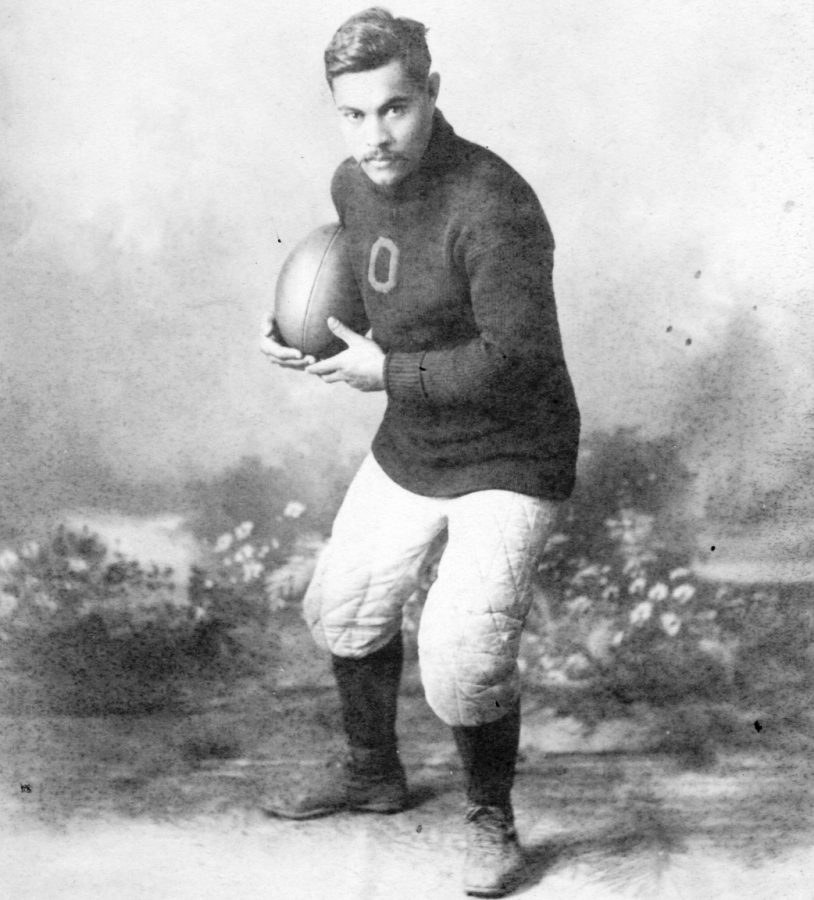

Remembering John Henry Wise, OC 1893, Revered Lineman, Hawai’ian Royalist

Photo Courtesy of Oberlin College Archives

John Henry Wise was a key figure in Oberlin’s football history.

When talking about Oberlin football, the conversation eventually diverges to the legendary Heisman era. But what about the other contributors during this time period, and what legacy did they leave behind at Oberlin?

John Henry Wise was born in 1868 to a German father and a Hawaiʻian mother. Originally a student at Hilo Boarding School, he was brought to be a part of the first class of the Kamehameha School for Boys by the Reverend William Brewster Oleson, OC 1877, who wanted to educate native Hawaiʻians on Christianity in hopes of spreading a Protestant revival across the island.

“These sons and grandsons of the first missionaries were looking for someone to lead Hawaiʻians back into the church,” Catherine Cruz and Sophia McCullough reported for Hawaiʻi Public Radio. “They knew they couldn’t do it so they were looking for a Hawaiʻian.”

Wise excelled in the classroom, and the Board of Trustees at the school voted to send him to study for three years at the Oberlin Theological Seminary in 1890, which was a rare exception for a native Hawaiʻian to pursue college.

“We do not want higher education at all in the Kamehameha Schools,” Reverend Charles McEwen Hyde wrote in the late 1900s on the subject of education within the seminary. “Provision for that will be made in other ways in exceptional cases. The average Hawaiʻian has no such capacity.”

While Wise noted the strict schedule — for instance, students weren’t allowed to leave for town without supervision — he enjoyed his time at the seminary and wanted to take advantage of the opportunities Oberlin gave him. One of these was the inaugural football team that formed during the 1891– 92 season, which he joined initially as a guard with two other members of the seminary. He is widely believed to be the first native Hawaiʻian to play college football and during his two years on the team, he was a widely acclaimed player. According to the Oberlin News, Wise was “able to run with three men on his back without noticing the extra weight.” He was also noted for his strategy and ability to execute gameplans.

“Wise went through the line every time he was signaled and kept a hole for the ball until the last of the second half, when the hole was filled by U. of M. quarterback before the ball could follow,” the Review reported in an issue on October 27, 1891.

When John Heisman began his role as Head Coach, Wise was part of a record-breaking season where they went 7–0 in the 1892–93 season. Notable highlights of that year included being the last in-state team to defeat The Ohio State University and playing a contentious game against the University of Michigan, in which historian and former Robert S. Danforth Professor of History at Oberlin Geoffrey Blodgett noted that it was unclear who actually won.

Wise returned to Hawaiʻi following graduation to do evangelical work and noted the disarray. When he was still in college, Queen Liliʻuokalani, the last and only queen regnant of the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi, was overthrown and placed in house arrest, and a provisional government was instituted in her palace. Hawaiʻian Evangelical Association leaders such as Hyde were dividing the members of the congregation with anti-royalist views, arguing that there was only the “civilized Christian party” or the “royal heathen party”, implying that they could only be Protestants if they were against Queen Liliʻuokalani. As a result, Hawaiʻians in these churches left for other sects, such as Catholicism or Mormonism. Wise, however, worked to advocate for the restoration of the Queen by speaking one-on-one to Native Hawaiʻians in the congregations, to the dismay of his former mentors and sponsors.

“John Wise, whom we have been educating at Oberlin for three years at a cost of over $2,000, has been doing nothing but advocating restoration and associating with royalists,” Hyde said.

As Ronald Williams Jr. wrote in his essay, “To Raise a Voice in Praise: The Revivalist Mission of John Henry Wise, 1889 – 1896”, Wise chose both his religion and the rights of native Hawaiʻians in the divide that HEA leaders were trying to wedge.

“Asked to choose between his nation and his God, Wise defended both against the attacks of his church leaders,” Williams Jr. wrote. “He challenged the assertion of his administration that their actions were part of God’s plan: he claimed his Christianity.”

Wise would take his love for his country even further and participated in the 1895 Wilcox Rebellion, where he met with fellow royalists, was commissioned to an underground army, and tasked with preparing guns near Waikīkī. However, he was tried for and sentenced to three years in prison on the same day that Queen Lili’uokalani was tried. During his time there, his two letters of pardon were denied.

“It is probable that the few remaining native insurgents will soon be released, except John Wise, a native educated at Oberlin, who has proved a fractious prisoner,” an 1895 piece from The New York Times titled “Honolulu May Release All Prisoners” read.

Wise was ultimately one of the last prisoners to be released. After his time, he worked a wide variety of jobs to advocate for Hawaiʻi language and culture such as delegating with former prince David Kawānanakoa at the 1900 Democratic National Convention, serving as a senator, translating Hawaiʻian legends for the Bishop Museum, and teaching the Hawaiʻian language at both the Kamehameha schools and the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa. Wise took his lessons learned from Oberlin and used them to put his people and religion above all else throughout the duration of his life.

“I so love America, and I love Oberlin for giving me this education, but my heart belongs in Hawaiʻi,” Wise wrote in a letter to his family.