m.A.A.d. city Reconfigures Rap

In new album, Kendrick Lamar successfully reinterprets the rap tradition of challenging contemporary politics.

November 9, 2012

Of the rapidly multiplying number of rap subgenres, socially conscious rap presents the greatest challenge to artists. Attempting to represent the problems faced by an entire marginalized group too often comes off as arrogant, and condemning society for not solving these problems registers as accusatory rather than inspirational. After enduring the overbearing diatribes of political raps from the likes of Lupe Fiasco, it was difficult not to approach newcomer Kendrick Lamar’s social commentary with skeptical caution. Happily enough, Lamar’s first album addressed domestic abuse, poverty and prostitution with a surprisingly light touch; Section.80 integrated personal struggles with broader political issues, engaging rather than alienating the listener.

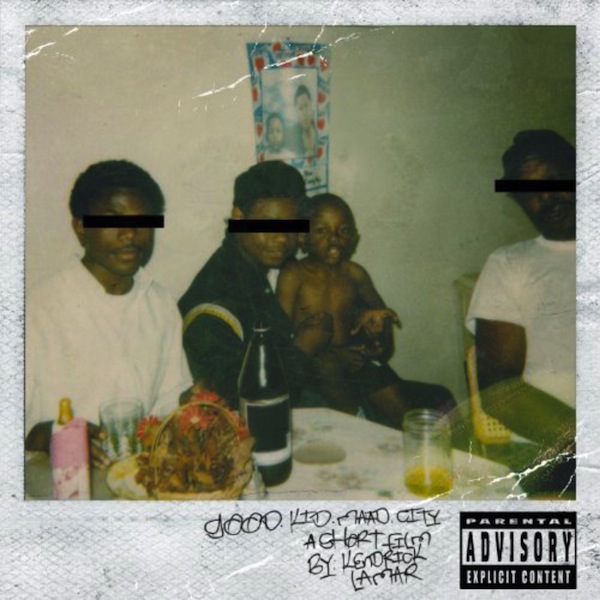

Picking up where Section.80 left off, Kendrick’s new, biographical album good kid m.A.A.d city proceeds to systematically dismantle politically conscious rap’s self-imposingly preachy tradition. Kendrick is not interested in making political accusations; instead, he accurately relates personal experiences to social issues, and social consciousness forms naturally through Kendrick’s experience of life in a lower class urban area. Politically charged themes most rappers address — gang violence, sexual abuse — appear in good kid, m.A.A.d city as natural aspects of Kendrick’s upbringing. The album is remarkably humble, which allows Kendrick to incorporate social awareness into a textured, accurate and often strikingly funny portrait of youth. Blessedly, Kendrick understands adolescence as a conflation of heightened moral conflicts and objectively ridiculous hormonal desires, and responds accordingly with humor and empathy.

“Sherane a.k.a Master Splinter’s Daughter,” the story of one of Kendrick’s first relationships, addresses the cultural pervasiveness of irresponsible sex in a cheekily self aware recollection of being “seventeen with nothing but pussy on my mental.” Seamlessly integrating cultural commentary into personal storytelling, Kendrick raps, “Love or lust, regardless we’ll fuck cause the trife in us / is deep rooted, the music of being young and dumb / Is never muted, in fact it’s much louder where I’m from.” The song ends with a voicemail from his mother, calling just as he prepares to lose his virginity. Interrupting teenage Kendrick’s fantasy of becoming “a professional porn star … enthused by the touch of a woman,” Mrs. Lamar loudly demands Kendrick “bring the damn car back” so she can “go to the grocery store and get food stamps.”

Regardless of comedic value, the ongoing presence of Lamar’s parents grounds Kendrick’s narrative in the adolescent struggle to rectify boundary-pushing culture and traditional family responsibilities. “Backseat Freestyle” — based off a rap Kendrick originally composed as a teenager — coalesces confusion and bravado, presenting the posturing of a teenager adrift in an overbearing world. Coming from most established adult rappers, lines like “I pray my dick get big as the Eiffel Tower / so I can fuck the world for 72 hours” smack of false machismo; in the mouth of an insecure 16 year old trying to impress a cooler crowd, Kendrick’s boasts express genuine longing. The jolting beat belies Lamar’s confidence, shuddering frantically as Kendrick spools off bravado.

Good kid, m.A.A.d city frames Kendrick’s struggle for identity amongst conflicting cultural norms around the abstract relationship between Kendrick and his hometown of Compton, CA. Lamar cannot claim ownership of Compton, or even what Compton represents; the city threatens to consume teenage Kendrick in a sea of conflicting standards.

“M.A.A.d City” raises the album’s stakes, thrusting listeners into the front lines of a gang fight; here, hometown pride, family honor, social posturing and drug use run together into something terrible and incomprehensible, a cultural flood Kendrick struggles not to drown in. “M.A.A.d City” jolts manically between verses, Schoolboy Q’s reassurance that “it ain’t nothing but a Compton thing” imposed over Lamar’s desperate narration of a near death experience. Halfway through the song, Kendrick’s narrative breaks into a frantic jumble, referencing everything from Pakistan to old horror movies. “Kill them all if they gossip, children of the corn, they vandalizing, option of living a lie, drown their body with toxins, / constantly drinking and driven to hit the powder and watch this flame, / that arrive in his eye, this is a coward the concept is aim and they bang it and slide out that bitch with deposits, / and the price on his head, the tithes probably go to the projects, / I live inside the belly of the rough, / Compton made me an angel on Angel Dust,” Kendrick exhales in a single breath.

In addition to being a breathtaking display of lyrical prowess, Kendrick’s rap displays an attempt — and ultimate failure — to conflate Compton into a single set of values. Compton contains too many powerful stories for anyone to claim ownership of, least of all Kendrick. All Lamar can do is record reality — the narrative of personal experiences, the voices of parents and friends transcribed verbatim, emotions associated with specific events — and try to make a story that is enjoyable, true and sincere.