Linfield Discusses the Role of Media in Revolution

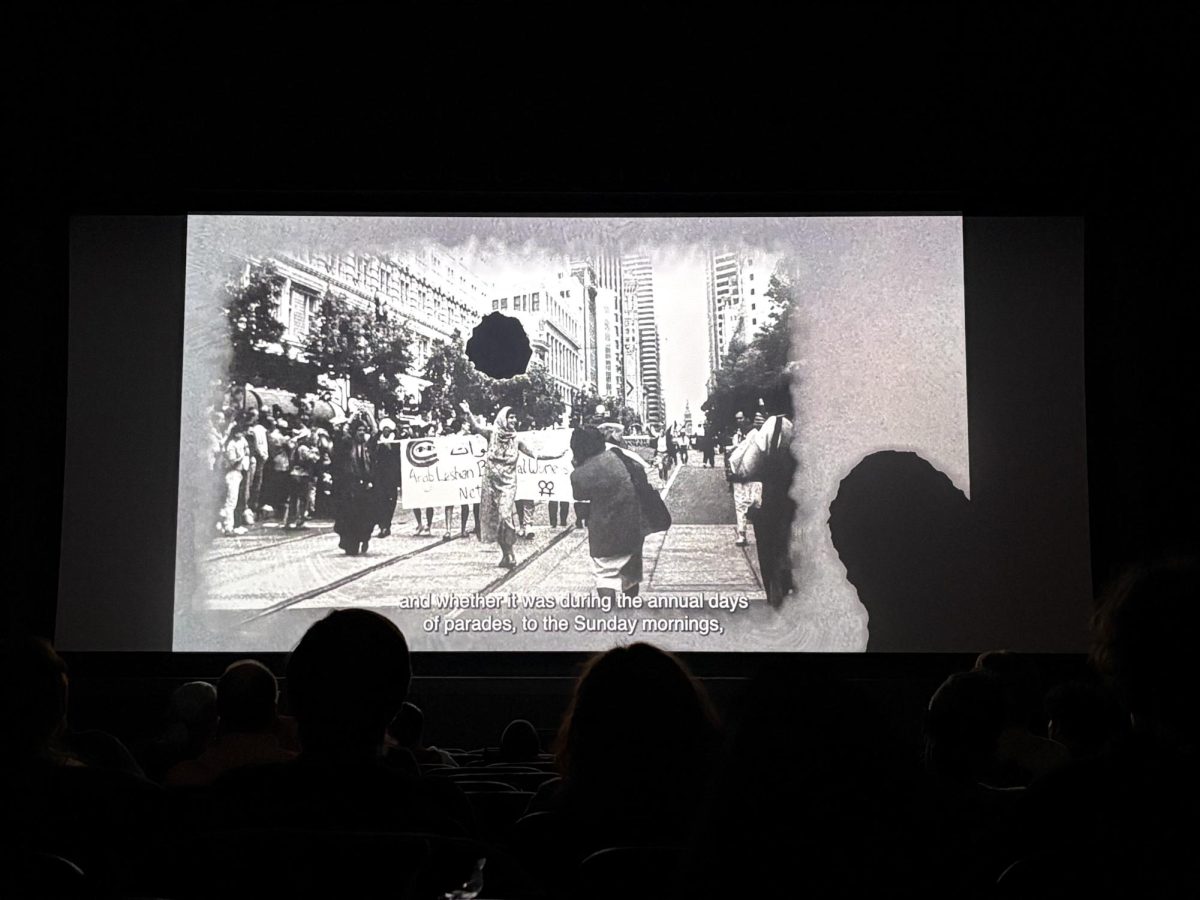

Linfield’s expertise in cultural criticism gave her a unique perspective on the Arab Spring for the “Documenting Violence: Photography, History, Memory” symposium.

November 16, 2012

December 2010, Sidi Bouzid, Tunisia. Angered by repression at the hands of an unaccountable, undemocratic government, street vendor Mohammed Bouazizi doused himself with gasoline in front of a local government office and lit himself on fire. His death inspired wave after wave of angry protesters to take to the streets by the hundreds, thousands and finally millions, sending shockwaves across the Middle East that toppled authoritarian rulers in nations like Egypt, Libya and Yemen. The news media labeled it a revolution like no other, with social media being an indispensable tool in organizing the movement. A new age of democracy was dawning over the Arab world, with Facebook and Twitter leading the way.

Well, that’s not quite how it happened, at least according to Susie Linfield, OC ’76.

“Social media is the province of elites,” she said. “Guns and armed forces were much more effective than the ‘Twitter revolution.’”

These strong words came from a lecture given by Linfield last Thursday in Hallock Auditorium as part of a three-day colloquium on photography and political violence. “Documenting Violence: Photography, History, Memory” included documentary screenings, faculty and student workshops and lectures by Oberlin alumni who have been behind the camera in Cambodia and other hotbeds of conflict.

Linfield, director of New York University’s Cultural Reporting and Criticism department, was clearly speaking from experience. Besides being the former arts editor of the Washington Post, she has served as editor-in-chief of American Film and as a critic for the Los Angeles Times Book Review, contributing pieces to the New York Times, Rolling Stone and other publications.

Linfield’s talk focused on points from her recently published book, The Cruel Radiance: Photography and Political Violence. She began by delving into arguments against the use of photography during World War II made by German critics Walter Benjamin, Siegfried Kracauer and Bertolt Brecht. She explained how photographs of bombed-out buildings may all look the same, for example, but this does not reveal the unique circumstances behind each larger conflict. Linfield also addressed doctored and edited photos, which she said can hurt the credibility of the medium as a whole.

“Photography is a new way of seeing, but it takes away human thought,” she said. “It is a weapon against the truth.”

The discussion then moved from the 1940s to the present day and, more specifically, social media’s role in Middle Eastern politics. Contrary to the proclamations of many Western news outlets, Linfield said, the importance of Facebook in movements like the Arab Spring is relatively minimal and the influential protests had in fact been planned months in advance. Linfield also pointed out hypocrisy within organizations like the Taliban, who once prohibited visual media before embracing it to spread their agenda.

“You can now become friends with President Ahmadinejad and the Ayatollah on Facebook, but the medium isn’t the message — the message is the message,” she said in a direct contradiction of communication theorist Marshall McLuhan’s famous aphorism.

The lecture was punctuated by a short question-and-answer session in which Linfield articulated her views on the Occupy Wall Street movement, coming to a similar conclusion.

“Social media works in a police state,” she said, “but sturdy democracies require the free flow of ideas.”