Julius Caesar, directed by College fourth-year Ansel Mills, closed this past Tuesday, taking the Shakespeare classic and using it to address the issue of climate change through a reinterpretation. A senior capstone for Mills, one of the themes he identified early on in the creative process was “what was [going on] with the climate in ancient Rome… [such as the storm] before Caesar’s death,” as explained in an email to the Review. This, in combination with the pre-existing political themes in Julius Caesar, is what made Mills think about how politics interacts with climate in today’s world.

“Just how the conspirators and Caesar’s conflict takes the minds of the people away from the world they are living in, so too do politicians often use the climate to pull support but then not always deliver a meaningful impact,” Mills wrote in an email to the Review.

The goal of the production was to show the relationship between regular citizens and politicians, to show a Rome affected by climate change, “and to show how the people choose to rely on their leaders to fix it rather than do it themselves.”

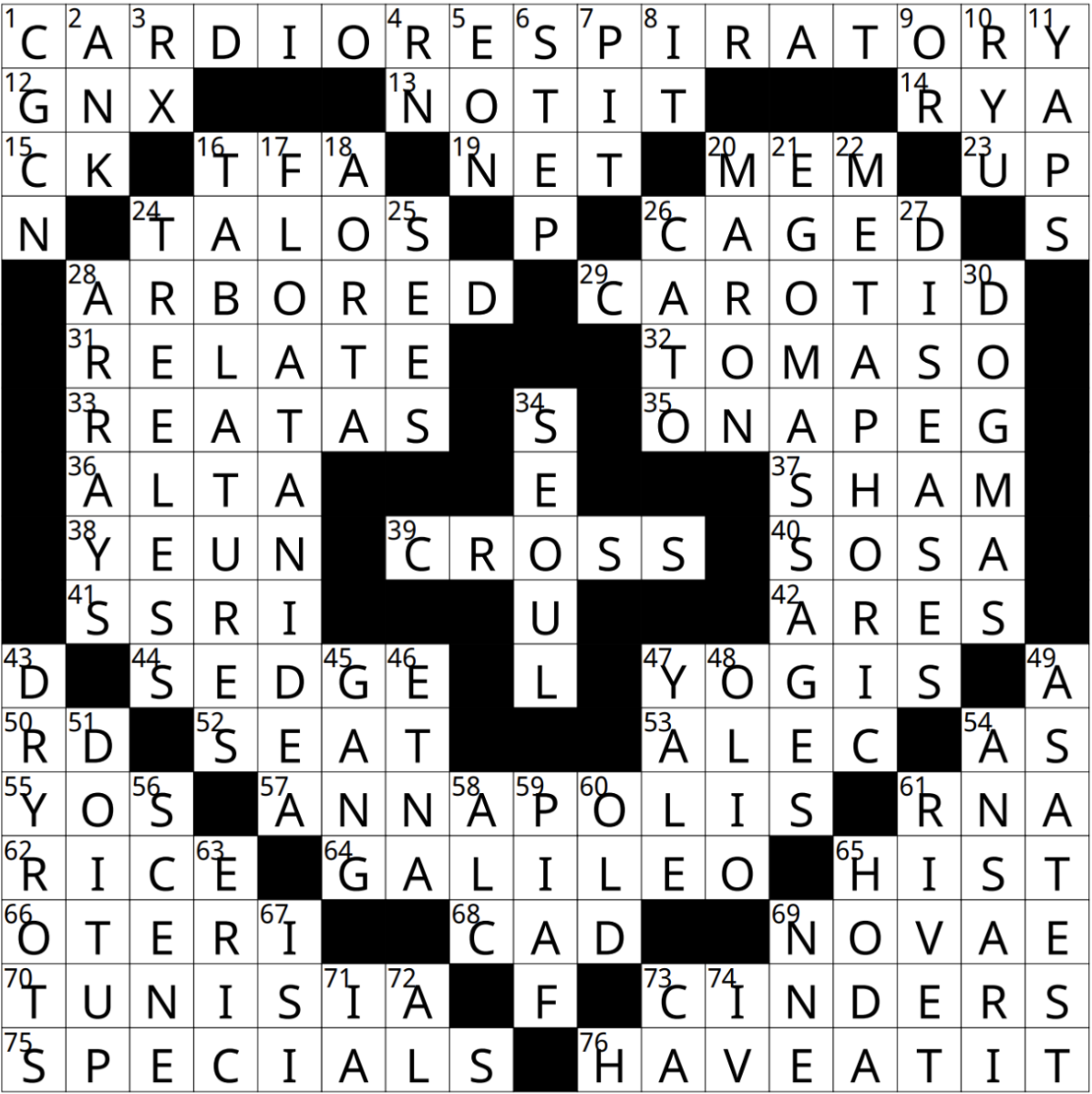

Though the intention is commendable, the execution left much to be desired. One of the ways the vision of climate disaster was realized in the production was through the set design. The structures in the Kander Theater were made of trash and debris, with wrappers strewn about the stage. For the creative team, the design was “a way of giving the people of Rome a practical way of involving themselves in the work of cleaning up the city.” However, watching the show, there was a general lack of acknowledgement of the trash itself that made it feel more like a mistake. It was often unclear what the set design was attempting to communicate, and this ambiguity of set design hindered attempts to understand the climate metaphor.

Although the message of the set did not come across, the structure of the set itself allowed for interesting creative direction. The intimate nature of the Kander Theater was perfect for the action in the show, allowing the audience to feel as if they were in the show at times. Most notably, when Mark Antony eulogizes Caesar, the actors sit in the aisle and we get to watch them go through the process of mourning, visibly getting angered and confused as they hear the story Antony has to tell.

Reinterpretations of Shakespeare are a common and powerful tradition in theater across languages, from an interpretation of Hamlet taking place in 1995 Kashmir to, more famously, a transposition of Romeo and Juliet taking place in Verona Beach. The ubiquity of Shakespeare allows directors to revisit these timeless plays while infusing them with new meanings and contemporary themes. In this case, however, the creative direction seemed to lack cohesion. There were moments where the intended message of the show was overshadowed by the classic themes of political corruption and betrayal.

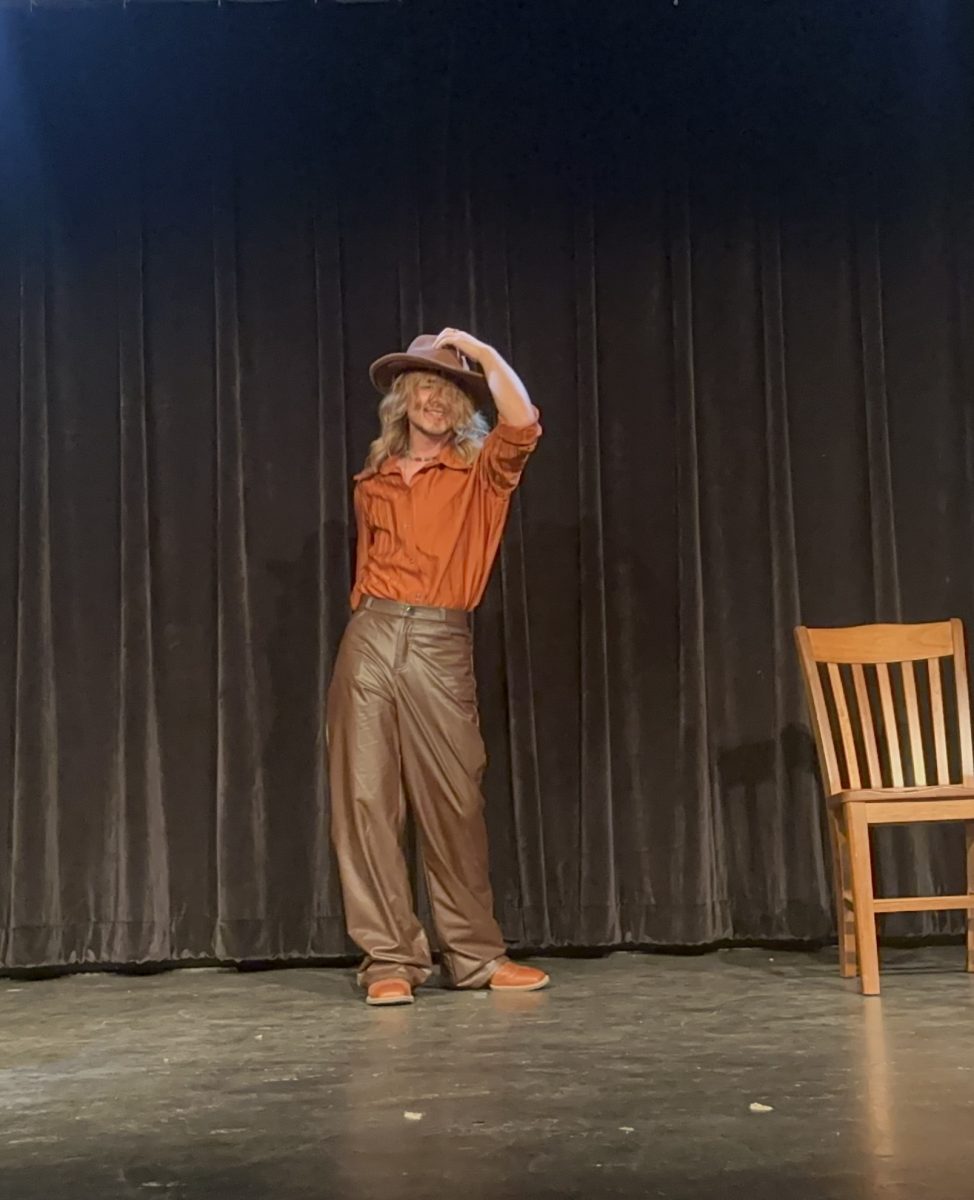

Despite these challenges, the performance itself was stunning. College second-year Jacob Fife’s portrayal of Casca was a highlight of the first act. His sassy delivery on Casca’s lines brought a fresh and humorous perspective to the Shakespearean lines, making them easier to understand. Fife’s performance added a delightful layer of wit and charm to the serious undertone struck by College second-year India-Mae Fraser’s Cassius and College third-year Ned Bannon’s Brutus, enhancing the overall experience.

Despite being featured in only one scene, College first-year Daisy Jemison as Portia was perfect in her role as the Shakespearean wife, echoing the likes of Lady Percy from Henry IV, Part I. She embodied the character’s desperate pleas as a wife to be included in the plans of her husband, leaving the audience wishing they could see more of her. Her performance was only amplified by the intimate nature of the set, and my seat in the first row allowed me to see the range of emotions Jemison expertly portrayed.

College fourth-year Jaden Labowe-Stoll delivered a measured and stunning performance as Mark Antony. He sneaks by in the first two acts as Caesar’s right- hand man, but from the moment he decries the actions of his fellow countrymen while mourning “the noblest man that ever lived in the tide of times” leaves the audience hanging on his every word. His delivery of the infamous speech wherein he eulogizes Caesar while rousing the crowd against the conspirators was captivating, and his command of the role itself was truly impressive.

Nonetheless, it is important to acknowledge the bravery and creativity behind the original vision of the play. Especially in the political climate we live in where life-threatening issues are leveraged for the goals of politicians, Mills and the creative team should be applauded for their work. The effort to draw parallels between modern issues and Shakespeare’s classics is a testament to the enduring pertinence of his plays. Although, in my opinion, this particular production of Julius Caesar did not succeed in realizing its ambitious goals, it serves as a reminder to the endless possibilities for reimagining the classics.