Since 2012, the Allen Memorial Art Museum has implemented a faculty-curated exhibition residency where professors spanning a wide range of disciplines work with AMAM staff and Oberlin College students to create an exhibition related to a class. A panel with Mildred C. Jay Professor of Medieval Art History Erik Inglis, OC ’89; Professor of Classics and Chair of Archaeological Studies Drew Wilburn; Associate Professor of Biology Taylor Allen; Associate Professor of History Ellen Wurtzel; and Eric and Jane Nord Associate Professor of Hispanic Studies and Chair of Hispanic Studies Ana María Díaz Burgos speaking on the Allen as a teaching space was slated to occur this afternoon, but it was postponed until April. Despite the cancellation, the Review met with professors who are to speak on the panel to discuss their residency programs.

As an Art History professor, Erik Inglis was a likely candidate for the residency. He worked with former Curator of Academic Programs Hannah Wirta Kinney to organize “Albrecht Dürer, Printmaker: Observation, Imitation, and Invention,” which was on display during the fall 2024 semester in tandem with his class, Albrecht Dürer and German Renaissance Printmaking (ARTH 219). During this time, Inglis employed what he called “Dürer hours,” an alternative to traditional office hours, where he invited students to walk through the exhibit with him and ask questions about the prints directly.

“There’s something wonderful that comes with the chance to ask questions about something and have people notice things that you might not have noticed before, without it necessarily being tied to a classroom lecture that needs to be done in 50 minutes,” Inglis said. “It also means that participants of all different levels of preparation have the chance to make really interesting original observations. Sometimes in this structured lecture of a 50-minute class, you need to get through the material so there’s not the chance to go: ‘Wait a minute.’… The Dürer hours can be much more freewheeling and so rewarding.”

Despite its benefits, Inglis will be unable to replicate this class structure, as there is a five-to-ten year non-viewing period for objects not part of the Allen’s permanent collection.

“I think it’s pretty much guaranteed I would never teach the class with that many [prints] on display again,” Inglis said. “I don’t think [it]’s likely to happen even 10 years from now.”

What is fortunate about Inglis not being able to have an exhibition up, however, is that it allows room for other professors, like Wurtzel, who curated “Science on Display: Cultural Experiments in Early Modern Science,” currently on view. While Inglis created his exhibition to use as a teaching tool, Wurtzel made the curation itself the topic of her lectures.

“I wanted [my students] to get a sense of the kind of foment of this period because it’s a really rich and exciting period of the scientific revolution,” Wurtzel said. “But I also wanted them to both acquire skills of research and the skills of putting together an exhibit, which is really not something that I’m at all an expert in. I think it did work out really well — several students have since written to me and said that they now want to go into museum work — and this class gave them the confidence to do that, but also a sense of how to do it right.”

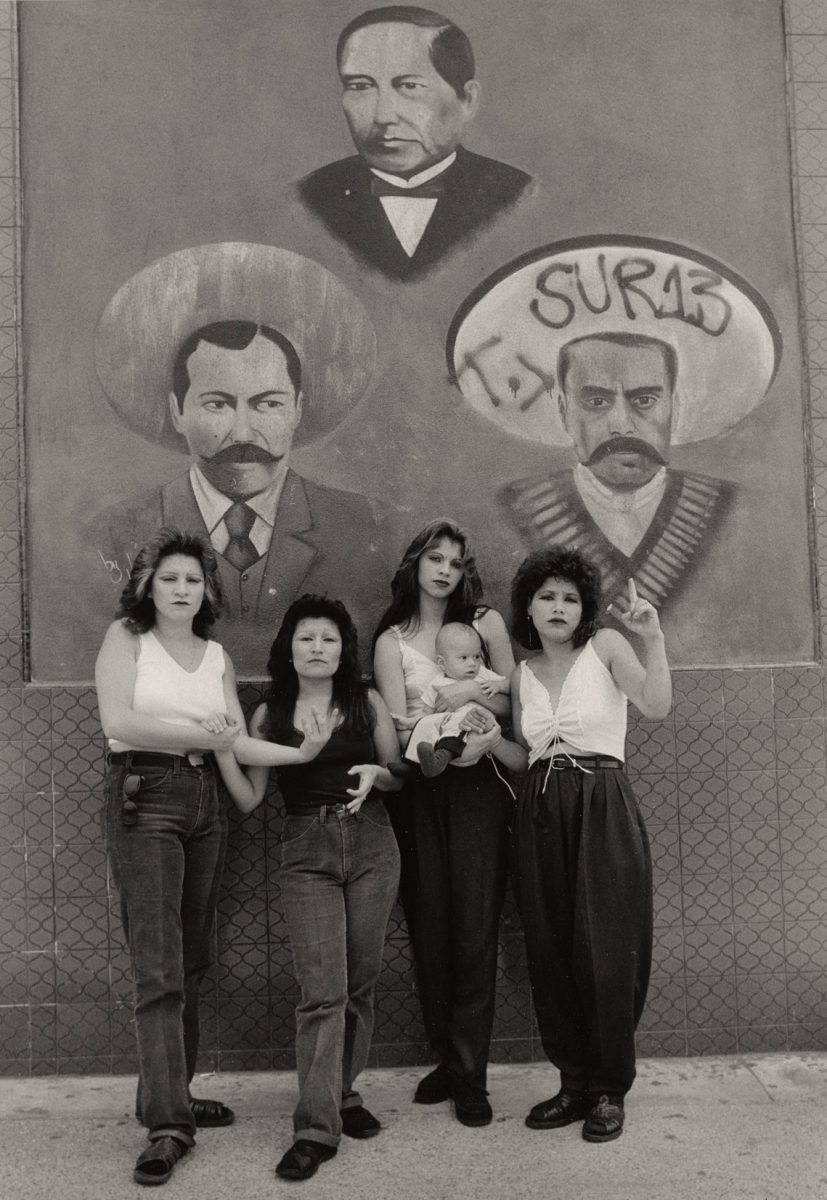

While departments such as Art History and History seem like obvious choices for museum curation, the Allen has also hosted professors from non-humanities fields. One example is Taylor Allen, who teaches Biology and co-curated “Women Bound and Unbound” in 2019. “Women Bound and Unbound” was curated by professors from four departments in addition to Biology: History, Comparative Literature, Religion, and Hispanic Studies.

“I, as a scientist, turn to the Allen Museum to introduce some ambiguity into what we study in the classroom,” Allen said. “For example, we study how emotions affect the body, and we look at it through the lens of science. An interesting approach would be to then ask, ‘Well, how would an artist see that?’ Sometimes [art] doesn’t capture what scientists see. Maybe it captures something more or something different. By introducing that ambiguity into the classrooms, I think it engages students a little bit more deeply than what I can succeed in doing in the classroom.”

Allen was successful in getting his students to be able to think and talk about science using thinking required of students studying art.

“I achieved my goal of getting students to collaboratively generate ideas within an umbrella of uncertainty where there is no certain answer,” Allen said. “What becomes more important is how you defend your reasoning, and so use the evidence from artwork or from literature or from science in order to defend your argument. Because you’re doing it in a group, the scientist has to be able to explain the science to the non-scientist, and the non-scientists need to persuade the science students among them. So it’s communication, teamwork, and leadership, in addition to all of the learning.”

Although professors are a necessary component of the residency, none of it could be done without the work of the Allen staff, particularly the Curator of Academic Programs Emily French. Even when they are not helping professors actively curate exhibits, they are working tirelessly to improve the program for years to come.

“We’ve been having some conversations in the museum about the use of different spaces,” French said. “We’ve added a couple spaces to the list of little galleries that faculty can use. It’d be great to keep thinking about where we can do these exhibitions.”