You and Me and Me and You Delicately Considers Identity Politics

March 15, 2011

In the 1980s and ’90s, the art world supported art that addressed the issues of race, ethnicity and gender. The artists involved struggled to find success with work that wasn’t about identity politics. Rikrit Tiravanija, in a gallery opening, brilliantly satirized the largely white gallery world’s insatiable hunger for exotic flavor by actually cooking them Thai food. Tiravanija’s point was well taken. When people of color make work about identity, are they filling a niche market? Does being not white condemn the artist to eternal conversations of identity?

Race, nationality and belonging played an important role in You and Me and Me and You, yet the senior studio duo show by Stephanie Lo and Sam Draisin lacked the sharpness of Tiravanija’s piece. Using weaving and large- format photography, the pair presented Oberlin audiences with the most direct political statement of the spring season thus far. Though straightforward and digestible, Lo and Draisin’s work lacked passion and excitement. Their artistic points were well taken, but far from ground-breaking.

In her statement, Lo outlines that her project is about navigating her Chinese and American identities. She attempted to “draw connections between myself and the surroundings of these two cultures” through weaving. Yet the giant woven works on the wall lacked any sense of the artist and the two cultures — only the act of weaving was on display. The materials — a stiff combination of plastic, yarn and paper — were unrelated to her subject matter: There was no link between the physicality of the works, Lo and her competing identities.

The color scheme of the woven pieces presented the only connection between the objects and Lo’s stated subjects — herself and her “two cultures.” One work was predominantly white, blood red and blue; the other, a monolithic red. The names of the two pieces could also potentially represent the United States and China as abstractions. “Attempt at Reconciling” — the white, red and blue piece — could be expressing the U.S. as a place where differences are sorted out or forgiveness is necessary.

The red woven object, “A Lifetime’s Worth of Fortune,” may be referring to China as a foundational past for Lo. Moreover, Lo’s process was more academic than personal. The objects looked like they were made for the gallery wall: They appeared like symbols of blankets rather than real objects in and of themselves. Does the meaning of “weaving” as a concept diminish if the result doesn’t look truly woven?

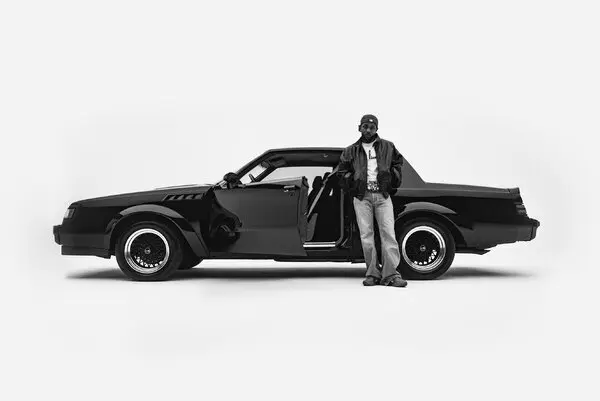

In his statement, Draisin expressed the desire to monumentalize the mundane occurrences in the everyday life of people of color. Draisin’s work displayed a rugged, craftsmanlike application of photographic skill. Imposing and delicately backlit, the pictures presented the viewer with a series of images focused on people of color. Floating on the wall and strategically illuminated, the pieces reminded the viewer of timeless familiar moments.

But perhaps they were all a bit too familiar. Anyone who knows Draisin’s work could walk away feeling like he’d seen this series somewhere before. What Draisin proved was something we already knew: He’s a great photographer.

Although Draisin stayed within his comfort zone, he did so emphatically. One photograph depicting College junior Lucas Briffa leaning against an alleyway wall, titled “380 Depot”, gorgeously toyed with focal planes. Another, “One Thousand Yards”, highlighted College sophomore Mali Sicora in sharp foreground, constructing a classically beautiful image.

Most exciting and most out of place, “Breakfast” depicted Draisin dressed in whiteface sipping coffee and reading TIME magazine. The photograph acted like a razor in a bowl of raisin bran, adding a much needed bite to the exhibit. It is unfortunate that Draisin chose not to hide more booby traps in the show. For an artist who likes to push the envelope, Draisin’s decision to make more accessible work missed the chance to keep the audience on edge.

How can artists like Lo and Draisin escape the confines of identity art? In a recent interview with The Root.com, the chief curator of the ongoing Glenn Ligon retrospective at the Whitney Museum, Scott Rothkopf, wrote: “Someone once said that [Ligon] makes work about being black and gay. … I replied, ‘That may be true, but if that’s the case, then it’s also about what it means to perceive somebody as black and gay, and in that sense, it really concerns everyone — how we understand and interact with one another.’”

Perhaps today artists of color can more easily transcend the labels of the ’80s and ’90s. In order to implicate everyone — to widen the scope to include both the perceived and the perceiver — the artwork does not have to be shocking. However, it must be resolved, exciting and razor-sharp. By leaving loose ends untied and prioritizing safety over risk, You and Me and Me and You remained indecisive. It resigned itself to being a small voice in a loud room.