Chamber Orchestra Performs Copland, Ettinger and Beethoven

April 22, 2011

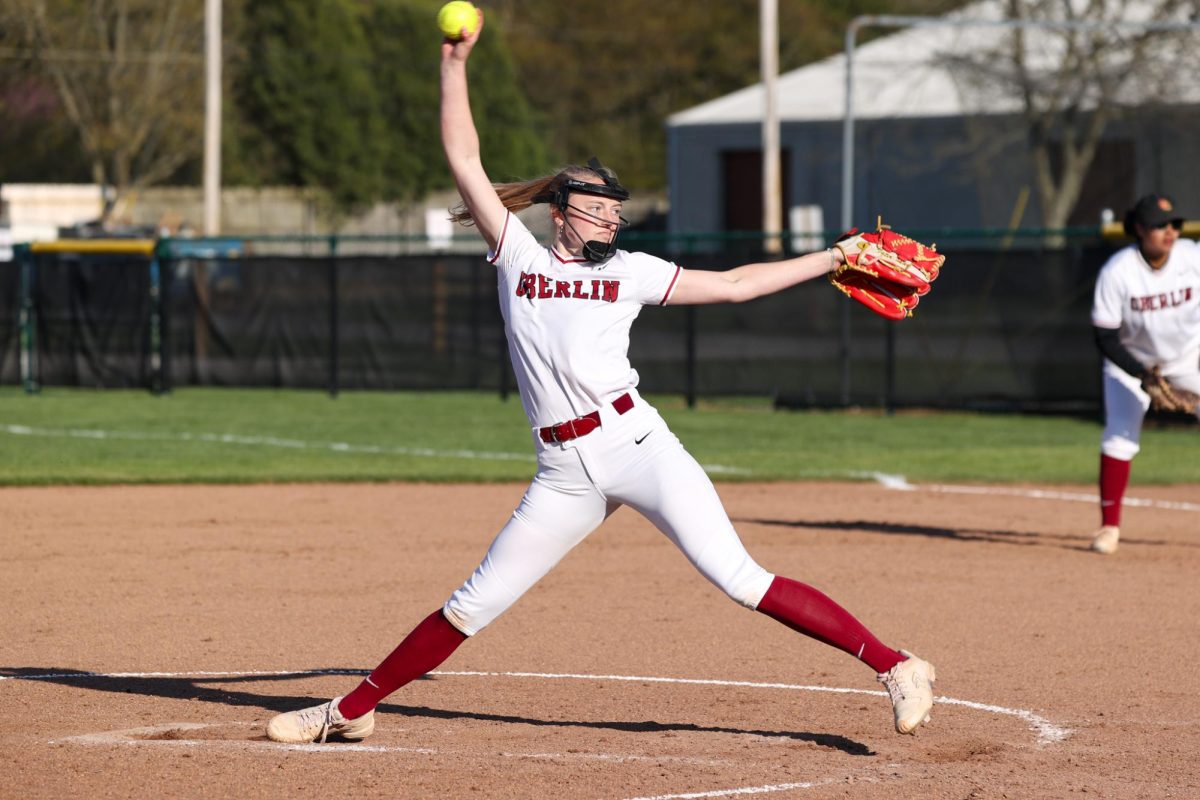

Last Tuesday evening, visiting conductor Mark Russell Smith conducted the Oberlin Chamber Orchestra in an exuberant program that sandwiched Conservatory senior Kate Ettinger’s pieceCaedo, Caedere between two time-honored classics: Aaron Copland’s Appalachian Spring and Beethoven’s Seventh Symphony. The combination of these famously optimistic works with the mechanically-inspired tumult of Caedo, Caedere turned the concert into a celebration of impending spring.

In the Conservatory’s year-long search for a new conductor, student musicians have worked with a steady stream of world-renowned visiting conductors. On Tuesday, Smith, director of the Quad City Symphony Orchestra in Iowa and a graduate of the Curtis Institute of Music, conducted with supple eloquence. Described in the program as “a champion of the music of our time,” Smith shares the Oberlin Conservatory’s fierce commitment to contemporary music. As a fellow audience member observed, “it seemed like he really knew what he was doing, which is good.”

The opening strains of Appalachian Spring grew directly out of the rainy darkness and the audience’s hushed excitement as the orchestra ebbed and flowed through pristine washes of sound. Originally composed as the score for a ballet, Appalachian Spring premiered in 1944 at the Library of Congress. Choreographer and dancer Martha Graham commissioned Copland to write the music for a ballet based on the story of a young pioneer couple’s marriage in rural Western Pennsylvania in the early 19th century. Later, Copland reworked the music into an orchestral suite that has since made its way into American popular culture.

Smith embodied the spirit of each of the eight sections in his conducting, and with the orchestra navigated smoothly between near-reckless folk dances and the Shaker melody “Simple Gifts.” The piece ended in a reverent stillness. As the muted strings fell into silence, a baby started to cry at the back of the chapel.

Caedo, Caedere explores the sounds generated by mechanical devices. Ettinger writes in her own program note that “the orchestra transforms the device into a living, breathing organism that seems to threaten its own maker with the awesomeness of its destructive potential.” The Chamber Orchestra delivered a compelling performance of the work, whose title derives from the Latin verb meaning to “chop” or “murder.” The string section provided an oceanic, abrasive wall of sound that was punctured insistently by the winds and brass, and pitched percussion instruments — glockenspiel, harp, celeste — provided a rhythmic texture above the otherwise static (and sometimes erratic) sound-environment. Waves of low timpani and bass drum rolls welled up periodically, catalyzing textural changes that swept through the whole orchestra. The overall effect was the feeling of a great, lumbering machine spiraling into and out of control.

After the intermission, the orchestra performed Beethoven’s monumental Seventh Symphony — a daunting endeavor for any orchestra. Though energy seemed to flag at a few key moments in the second movement, the orchestra, masterfully conducted by Smith, successfully tapped the deep and sometimes desperate extremes of the symphony. The concert ended with the fourth movement’s wild frenzy of driving rhythmic motifs and soaring melodies.