Off the Cuff with Lieutenant Dan Choi

West Point graduate and Iraq war veteran Lieutenant Dan Choi has been a figurehead of the gay movement since coming out on The Rachel Maddow Show in March 2009. As one of the founding members of Knights Out, an organization led by gay and lesbian West Point graduates who serve as facilitators between LGBT troops and army officials, Choi had an instrumental role in the struggle to repeal “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell.” He will be visiting Oberlin this Tuesday, Feb. 14. In a telephone interview with the Review, Choi shared his thoughts on the tenets of activism, falling in love and the conflicts within the modern gay movement.

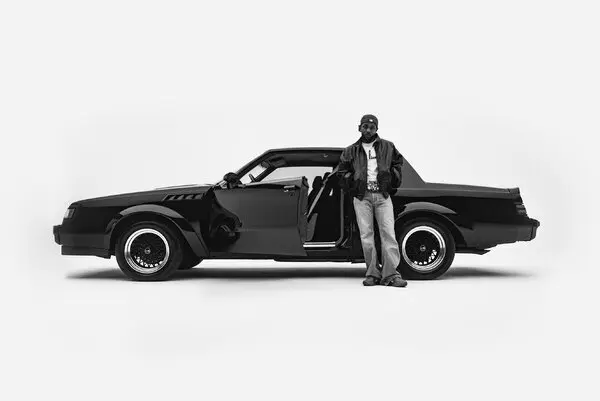

Lt. Dan Choi will speak in Finney on Feb. 14 about his experiences fighting against “Dont Ask, Don’t Tell.

February 10, 2012

What made you decide to join the army, and did “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” give you reservations about joining the service?

I joined because I saw Saving Private Ryan and Forrest Gump and a couple of other movies. That was really all it took. … My brother actually wanted to go to West Point and had a brochure for it that he left on the coffee table. He got a nomination but didn’t finish the application because there were so many white people at the school. He told me that WP stands for white power and that I had to watch out when I was there. I thought about how, as an Asian American, I’ve seen so many stereotypes about Asian men — either we’re good at math or we’re good at kung fu. We don’t know how to drive, and we’re short and don’t stand up for ourselves. I never really had any role models in the media that I could look up to as an Asian boy. So going into the military I was more of an Asian activist, I’d have to say — openly Asian.

Did that change once you got to West Point?

The first day I got there they asked us if we understood “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell.” You have to sign a contract that says you won’t do drugs, won’t drink, won’t have sex and you won’t be gay. I’ve known I was gay since the fourth grade but always thought it was a phase or a sin or something I could change. I thought, “Why would I ever say I’m gay?” … I think for me and for a lot of young kids joining the army, they don’t identify as gay. They think, “I’m not one of those gays.”

What I really learned at West Point was morals, was living by an honor code and understanding why that code matters. It is so important to tell the truth in the army. In war, a lie can mean death on the battlefield, and it is not hyperbole to say that. I was inculcated to tell the truth, but I never thought that I was lying. I believed it was a white lie at worst, something to keep the people around me from feeling uncomfortable.

Tell me about how you got from that point to coming out on The Rachel Maddow Show.

For 10 years, I didn’t have a voice. I lived for 10 years under “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell.” But in 2008 I fell in love. It taught me a lot about being closeted. I feel if you just think of it as an individual pursuit it seems okay; you think, “I’m just hurting me.” But then, at 27, I fell in love for the first time. I’d never dated before. I finally understood what all these straight people were talking about and why they talked about it so much. I finally understood why it was so important for my fellow soldiers to write the letter, the last letter to their wife or girlfriend that they keep in their pocket in case they die in Iraq. When you fall in love, you know why life is worth living. … I was suicidal a lot when I was growing up, knowing that I had to live a lie and not really being sure that I could do it. I think a lot of gay kids struggle with that. Even though I knew gay people were getting married, I never had gay friends or identified [with the gay movement]. I’d had flings and substance-less relations but never a relationship.

I had thought about going back to Iraq, and everyone was telling me I was needed in Iraq. But I thought to myself, “Now that I’m falling in love, how can I go back to Iraq? If I die the letter wouldn’t even be given to Matthew.” … So I decided I couldn’t do it anymore. I couldn’t go to work every day and have people ask me questions about Martha. That’s what I told them: that her name was Martha instead of Matthew. I was telling this elaborate lie for the first time in my life. It’s one thing to deny you’re gay and say, “Oh yeah, I love those hot women, I love their eyes.” Of course the guys would say, “What do you think about her tits?” And I would say, “She has a sparkling personality.” You get better about lying about those little things after a while, but that didn’t hurt me. Now it was really hurting me because this relationship was changing my entire life. … If it weren’t for that relationship, I wouldn’t be doing any of this.

After deciding that you no longer wanted to conceal this part of your life, what steps did you take to make that information public?

I should mention it wasn’t following politics at all. My friends all said, “Obama is going to repeal “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell.” I had no idea what that meant. I knew about the policy, but I hadn’t researched it or anything. Then after the election I saw on the Internet that people were protesting the presence of anti-gay minister Rick Warren at the inaugural service. I started to get it; this is my community. Then I flew home to come out to my parents. … My dad is a minister and my mom is a nurse, and they don’t even know the word “gay.” It wasn’t easy to do. In the moment I told them, I felt so much judgment, but it also felt so freeing. I was finally able to log on to an Internet website for gay West Point grads. It was this secret thing, but there are like 500 people on the site. … Then I started meeting with some of the members’ mentors. There was one guy who was like 60 years old who had been in Vietnam and actually been a professor at West Point at one point and is a millionaire now. He’s a typical West Point grad, but he is gay and getting married to his boyfriend. I was like, “Wow!”… I went to their homes, and they would show me their veteran uniforms. That made me cry. Straight veterans all have this stuff, and when they show you it’s like, “Oh la-di-da.” Then a gay veteran shows you the same thing, and it’s like, “Holy shit, you should have been my mentor from the beginning.” But these same veterans said, “Don’t come out. See what I have? If you come out you’ll lose everything.”

Well when you were discharged from the National Guard did you feel like you’d lost everything?

I don’t want to give a black-and-white answer. I knew the risk of coming out publicly, and everyone was telling me not to do it. I thought long and hard before I did it, but I still didn’t know what it would feel like. As much as you can prepare for it and as much as you know what’s going to happen, it does feel like everything is being taken away from you. They took away my medical benefits, I thought they might take away my West Point ring. On paper it said honorable discharge and moral dereliction. I thought, “I’m telling the truth, and I’m being told I’m morally derelict.”

Both gay and anti-gay groups were telling me not to come out. A gay veterans group told me it disagreed with what I was doing. … I thought it was such bullshit — gay people telling other gay people to stay in the closet. … When I finally came out, all of that was running though my head, and I was so mad. [In March 2009] we started Knights Out, some 30 of us. … An article was written here and there, people would call — we did an interview with the Army Times. People would ask if we knew the consequences. They didn’t want me to talk about my relationship. You’ll notice that in the first Rachel Maddow video I didn’t talk about Matthew or about love. I just talked about truth. All the lawyers for the gay activist groups said, “Don’t talk about your boyfriend or you’ll get a worse discharge.” And I thought it was so chickenshit. We’re in the army, we’re soldiers, we risk our lives in combat. Do you think I’m scared of getting a worse discharge? Woop-di-doo.

You’ve become a leading activist for LGBT rights and have participated in both traditional forms of protest, such as consciousness raising and petitions, as well as more radical ones, such as hunger strikes and handcuffing yourself to the White House. In your experience, what type of protest do you find to be most effective?

I don’t think that handcuffing yourself is radical — it’s showing an appropriate response. … I think after a whole year of just playing nice and going to these cocktail parties, we would still just agree to disagree at the end of the day. I was on TV all the time, but I felt I had very little control over anything. I would visit schools and do petitions and go to rallies and it was like, now what? We have to wait for Congress. I thought, “No. It’s finally time to make it clear to everyone how painful this has been.” And I don’t think doing it in a suit with a script and makeup on your face and good lighting has anything to do with that. I was on CNN for [all of these] interviews and thought, “God, I’m such a farce.”

Obama was not doing anything to repeal “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell.” People were saying, “Oh that’s not true, he loves you. He always talks about you.” I said, “Okay, he talks about us but he doesn’t do anything.” …. So I started wondering if we could risk this. I think that’s a question that a lot of activists ask themselves, like in the Occupy movement — when have we reached a point when we’re pushing against a wall and we’ve done all the things we can do? Everyone has opinions on what makes a great activist. … I think there are only two real qualities of a good activist. One, you’re willing to go to jail and two, you’ve told off your boss. … You have to stand up to what you know is so hard to stand up to: authority. That’s the fight. Writing a book or posting something on Facebook is one thing, but the fight is really when you tell the people who oppressed you, “No more.” … You can tell activists to contain themselves, but it will always explode. At some point or another there will be a day of reckoning. Pick your day.