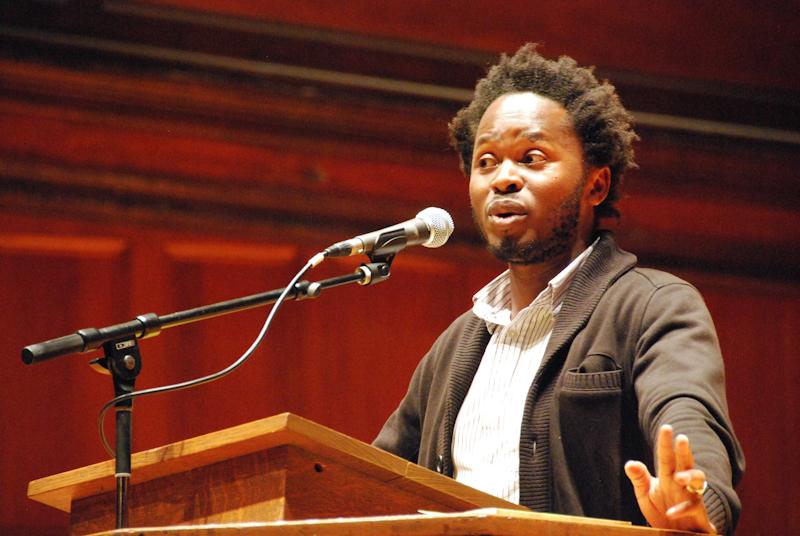

Off the Cuff: Ishmael Beah, OC ’04, human rights activist and best-selling author

Ishmael Beah, OC ’04, former child soldier and best-selling author, gave a convocation this Tuesday titled “An Evening with Ishmael Beah.”

September 12, 2014

Human rights activist and Sierra Leonean author, Ishmael Beah, OC ’04, rose to fame with his best-selling memoir A Long Way Gone: Memoirs of a Boy Soldier. One of the world’s leading advocates for children affected by war, Beah sat down with the Review to discuss his rehabilitation experience, the narrative structure of Mende, his native language and his perception of beauty.

Obviously you’ve experienced more tragedy and brutality in the span of a few years than most people have in a lifetime, the kind of tragedy that most people would want to run from. What fueled your want — or need — to construct a memoir from your experiences?

When I started writing it, it was more that I wanted to make sure that I was living in the United States and experiencing newer things. I felt that I wanted to document some of it, perhaps for when I had a child. It also started by the fact that I wanted to prepare myself to have a very elegant or succinct debate about what had happened if I had the opportunity, because there had been a few moments where I had a chance to speak, but I wasn’t prepared enough to say.

With time, it became something that was more out of frustration of how my country, and the war that occurred there, and the issue of children and armed conflict was spoken of in the international media. I wanted to say something from somebody who had experienced it personally — to give the context that was missing. The Western media was more sensationalizing things; it was a way of speaking about it as though we all just wanted to be in this madness — that people just woke up one morning and they wanted a war. Even when my country was spoken about, it wasn’t that there was a Sierra Leone before the war, or things that led to the war. There was no way that we woke up one morning and said, “Let’s have a war today.” There were things that led to the war, and that context wasn’t presented. So for people who came to know my country through that, that’s all they knew.

You’ve clearly had a lot of experience with child soldier rehabilitation services, both through your own personal experience and through your work with your foundation. What are some of the things that you’ve learned both through your own rehabilitation process, and subsequently through assisting the rehabilitation of others?

What I’ve learned is most important is that people have good intentions, to go to these places and want to assist. But often times they belittle the intelligence of the people they want to help. In the long run, they need to put structures in place that will allow people to continue the work that they start. Because when you go and try to rehabilitate, you have to do it in communities they’re coming from and create structures that will sustain themselves. If you don’t do that, then when you leave the whole thing will collapse.

There hasn’t been much market research done to see how you provide opportunities to people coming from conflict, not just rehabilitating them psychologically. Because after that, what do they do with themselves? You need to talk to people to see how they can be a part of it, instead of imposing what you think they should be doing. For example, when I was coming out of the war, people would come and say, “We think everyone should be a mechanic or a plumber.” Well, OK, if somebody wants to be one, yes. But if you’re in a country that has no more than 10,000 cars and you’re training 20,000 people to become mechanics, that doesn’t fit.

There’s a mistake when people think that when [others] come out of the war, they don’t know what they want, or they can’t think soundly. But you have experienced life enough to not want to waste any time. You’re intelligent enough to know what you want, because to survive war requires a lot of intelligence.

I was reading a little bit about the narrative structure of Mende, your native language, which is inherently image-rich. Can you describe how growing up with this language may have influenced the way that you see the world, or how you tell stories?

When you grow up in the culture, you don’t think it’s exceptional. It’s just what you do daily — just how people speak. It was only when I started trying to translate that into English that I thought it was beautiful. For example, how you say that you’re upset in Mende literally translates into saying that your heart is on fire. When you are upset, you feel that way. Or, for example, if you say that you are not upset anymore, you say that your heart is like cold water, because it means that your heart is normal temperature.

There are things that are just part of the way we spoke. How you talk about a ball, you call it a nest of air. It’s never in our minds flowery — it’s just how we spoke, how things were. Because of the orality of how we tell stories, you don’t have them go back to read a sentence. You need to capture their imagination. I think the language has a lot of techniques to do that — of imagery, of things like that. So when I started writing, I would think in that language and try to find the English equivalent. That’s when I discovered that it was an advantage to me as a writer.

You reference beauty continuously throughout your memoir. Can you speak to how your experiences with violence and brutality influenced your perception of beauty?

I think for me, what I’ve seen is that often times we want to see things black or white, good or bad. Beauty only exists when everybody’s laughing — absolutely not. Just like life, being alive or having life within you exists through hard times and through good times, so beauty exists, even in the most horrible things. It doesn’t die away completely. But you have to be able to see it. And sometimes you can see it more, because it’s the only thing that you can hold on to. So, for example, I think, during the war, I had moments when I stopped just to feel a breeze, and you realize it feels so good to feel a breeze because you nearly just got killed, and you appreciate it.

So I think what happens is because you begin to realize how fragile moments are, you begin to slow down to appreciate it — the simplicity, the beauty of every action.

There are also a lot of relationships that get formed in the war. It’s not just in my war, the civil war, because I was a kid — you talk to veterans from Vietnam, from Iraq, and they also tell you about brotherhood. Seeing the worst and the best of each other. When you see the worst and the best in each other you get to know them perhaps deeper than you would if they were your brother. There is beauty in all of these things.

You’ve asked in other interviews how one can “move into the future while the past is still trying to pull at you.” How would you answer that question?

In my case, what I’ve learned is to take lessons from the past. Don’t allow the negative aspects of it to weigh you down. So I take things that strengthen my character and then move on with it. When something happens to people, I think our natural response is to think that it’s all bad. And for a while, I did that, but I couldn’t function. Having been a child who fought in the war was horrible, but yet it strengthened my character.

You know, I learned discipline, being in the army, and I used that in my studies. Because I knew how to sit somewhere for hours, and tell myself that I was going to focus and I won’t be distracted. I’m very observant. It’s something I learned from being a soldier, because you have to pay attention to details very quickly, otherwise things happen. And that helps me with my writing now. I can observe people very deep, and go just beyond what I’m seeing. So that’s how I use them.