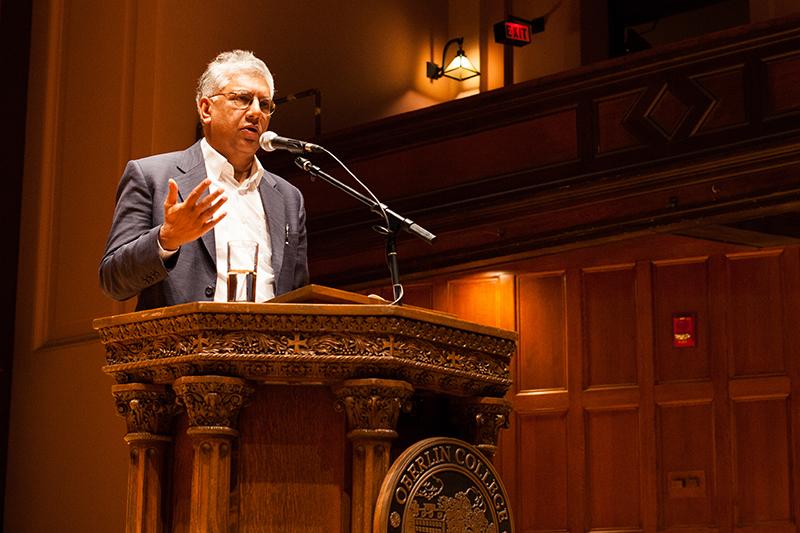

Vijay Seshadri, OC ’74, Salutes Oberlin in Final Convocation

Pulitzer Prize-winning poet Vijay Seshadri, OC ’74, returned to Oberlin this past Tuesday to present the year’s final con- vocation. His talk featured selections from his most recent poetry collection, 3 Sections, and older material.

April 10, 2015

This year’s Convocation Series ended on Tuesday at 7:30 p.m. with the solemn tones of Vijay Seshadri, OC ’74, reading his Pulitzer Prize– winning poetry. Born in India but raised in nearby Columbus, OH, where his father worked as a chemistry professor at Ohio State, Seshadri showed strong inclinations toward poetry and philosophy at a young age. At 16, he enrolled at Oberlin as a Math major but transitioned into Philosophy after an inspiring encounter with Pultizer Prize–winning poet Galway Kinnell, whom he cites as the “efficient cause” of his poetry.

After graduation, he pursued an MFA in Creative Writing at Columbia University, where he delved deeply into tracing his Indian heritage by translating works from Urdu and Hindi into English. His original poems and essays have appeared in countless acclaimed publications,and he has worked as a reviewer for The New Yorker and The American Scholar. He currently directs the graduate non-fiction writing program at Sarah Lawrence College in New York and has recently published his prose-tinged fourth book of poetry.

Seshadri began the convocation on a personal note after being introduced by President Marvin Krislov. He spoke to Oberlin’s “great flowering of poetry” in the 1970s after the founding of Oberlin Press’s yearly poetry journal, FIELD, in 1969. He also described his reverence for his father, who passed away this past February. In his father’s honor, he began by with two poems from his most recent collection, 3 Sections, which won the Pulitzer Prize in 2013, and which he described as “imbued with his [ father’s] presence.” These poems dealt with the issues of death and the afterlife and drew ideas from the Mahabharata and Aesop’s fables, which, as hestressed, “originated in India but were popularized in Greece.”

From here, Vijay flipped open the pages of his older works and read poems that ranged from descriptions of “three apocalypses occurring before signing for a FedEx package” to the scientific breakthrough of engineering moths with jellyfish genes to produce fluorescent silk. Building on the antiquated and languishing linguistic style of Yeats and Wordsworth, all of his poetry — spoken with the dry and slow articulation one expects from a classical poet — seemed to weave together the intersecting ironies of modern American life. However, hints of riddle and expressionism rang through in his poem “Nursing Home,” which wrestled with the topic of Alzheimer’s disease. He closed the convocation with a poem titled “The People I Know,” which stressed the poetic trope of “sameness” between individuals, even within our secular and data-driven American culture.

This theme of seeking clarity in our modern world through more classical poetry is no accident. Seshadri views poetry as “an object” and, in turn, sees the poet as a sculptor that fashions the “materials of meaning and feeling into form.” However, these notions are a relatively recent development in Seshadri’s style, which stemmed from the tradition of Midwestern surrealism and deep image poetry, which he claims are “still in [his] genetic code.” He also credits his father’s empirical attitude as a scientist

and his study of mathematics at Oberlin for imparting him with a yearning for elegance and simplicity in his writing, as in the basic proof of a complex theorem. This is not to say that Seshadri’s poetry does not tread in the realm of the political. His poem “The Disappearances,” which describes finding oneself at a cataclysmic point in national history, was published on the back cover of The New Yorker on the day after 9/11.

Although one would not describe him as an activist, Seshadri grew up in the era of the Poets Against the War in Vietnam movement and explained that his desire to understand his voice as a person of color partaking in history was what eventually

led him to abandon his early surrealist style. He said that he admires classical poetry, slam poetry and hip-hop alike, in that they are all a “sonic experience” to him. Recounting Bill Murray’s very theatrical reading of American poet Wallace Stevens’ work, Seshadri believes that it is false to distinguish between performed and written poetry, as it is all heard by some voice in the head eventually. He is also a big fan of Odd Future Wolf Gang, but he hasn’t listened to Kendrick Lamar’s new album yet.

Seshadri graduated from Oberlin in the same year that Barbara Streisand’s “The Way We Were” was at the top of the charts, and has many thoughts about how the school has changed. More generally, as the teacher of an undergraduate writing seminar course at Sarah Lawrence University, he complained that “college is getting easier.” In fact, while Seshadri was at Oberlin, he took courses that covered all three of Kant’s dark and dense critiques in a single semester and all of Shakespeare’s plays in a year. He is said to have “a great respect for identity politics” and is happy to see that students are hungry for more rigor in their college experiences.

Still, he joked about the irony of Oberlin’s slogan, “Learning and Labor,” as a remnant of the “Calvinistic embrace of labor” in a university that sold its seminary back in 1964. Some things never change.