On the Record with Jon Fine, OC ’89, Guitarist and Author

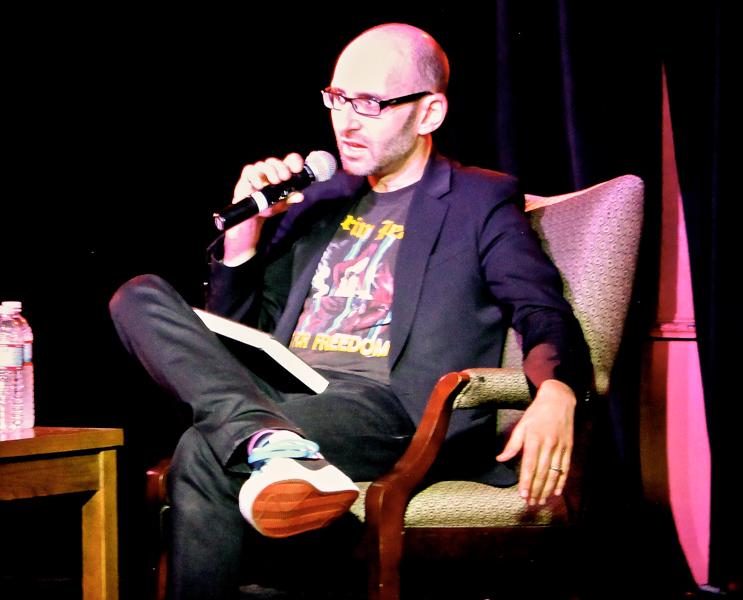

Jon Fine, OC ’89, guitarist and author of Your Band Sucks: What I Saw at Indie Rock’s Failed Revolution (But Can No Longer Hear), who came to Oberlin for a question and answer session Wednesday.

November 6, 2015

Jon Fine, OC ’89, released his memoir, Your Band Sucks: What I Saw at Indie Rock’s Failed Revolution (But Can No Longer Hear) last May to rave reviews. The book explores the rise and fall of the boundarypushing, genre-defining indie rock scene he helped establish during his time with bands like Don Caballero and Bitch Magnet, which formed at Oberlin during Fine’s first year. This past Wednesday at the ’Sco, Professor of Sociology Rick Baldoz hosted a question and answer session with Fine, who currently serves as executive editor at Inc. magazine. The Review spoke with Fine about WOBC, Ronald Reagan and the downsides of touring with a small band.

You talk a lot in Your Band Sucks about people with surprisingly similar interests suddenly being in the same room. I know that feeling.

That was magical. You’ve got to understand, that was incredibly important. Forgive me for getting all, “Let grandpa tell you how things were in the early 1900s,” but this is the ’80s. There’s no Internet. There’s no means of communication. Finding a record was a hard thing. One of the great joys of this culture back then — and one of the great limitations — was the handmade nature of it. Everything had to be handed off, literally in person. If someone wasn’t giving it to you in person, they were physically putting it in an envelope and getting it to you. There’s no Amazon. There was no record store doing any mail-order of any scope whatsoever that you cared about. You were dealing directly with the people that you dealt with. And not only that — if you grew up slightly weird in a high school where there weren’t others like you, you could just actually think, like, “Oh, I guess this is how it’s going to be for the rest of my life.” You cannot imagine the joy and relief at finding people like you — finding your tribe, really. It is so huge to find your people.

Was the first time you discovered that culture and found your tribe at Oberlin? Absolutely. I grew up in a very comfortable suburb. I was very well taken care of in that sense. It was 40 or so miles from New York City, but it may as well have been a million miles away. The area that I grew up in, in the 1984 election, it went approximately 10 to 1 in favor of Reagan. There were kids in high school with Reagan stickers. Like,

“Really? You’re going to be old and boring now?” There were five or six freaks I hung out with. Everybody hated us. We hated everyone, but they probably hated us first. It kind of sucked.

I got to Oberlin not knowing that it was going to be one of those places where it was all those people — one of those schools where the five weird kids went. There were actual bands in Oberlin writing and performing their own music. There were people there doing band things. Guys in bands in high school would be like, “I guess we’re going to try to write a song.” People would be like, “Whoa. Wait, what? You can do that?”

At Oberlin, there was a very important band called Pay the Man with Chris Brokaw, who has done a million things, and Orestes Morfin, who ended up in Bitch Magnet. I hope some of their recordings at WOBC still survive.

You talk about how you would go on tour and play shows in all these weird little towns.

We weren’t even that much older than you. I was 22 when Bitch Magnet broke up. I did that stuff pretty early. You probably will and should do that. I do readings, and there are primarily older people there. They’re like, “Oh, we did this, but the kids today can’t do it because of the internet.” I’m like, “Well, hold on. You and I aren’t going to hardcore shows in someone’s basement anymore. So, this circuit still exists. Just because you and I aren’t interfacing with it doesn’t mean it doesn’t exist.”

There seems to be an extremely limited group of people that are all in touch with each other and all play shows with each other.

That’s how it starts, and it grows from there. The difference between my generation and yours is, in a lot of cases, you really didn’t know what was going to happen until you got to town. I mean, you kind of knew certain things. Like, Champaign, IL — everyone stays with Poster Children. In Louisville, you stayed at Rocket House, which is where a guy named Jon Cook lived and where the bands Crain and Rodan lived and practiced.

But in a lot of towns, you would play your show, get on stage at the end of the night and say, “Thanks. By the way, um, if anyone can put us up, we’re clean and not crazy. We’d really appreciate it.” And some of them, you’re still in touch with 20 years later. The generosities of people that essentially didn’t know you at all were unbelievable. It’s moving for me to recall it to this day.

With a lot of bands that feature angular guitar lines and complex time signatures, I often feel like there’s a human element missing. But with Bitch Magnet, there is an emotional experience at the forefront. Did you feel aware of that?

I was. Sooyoung Park was the singer, and he basically wrote the songs. There’s a scene in the book where it was our senior year. It was one of those waning fall days, and I was feeling sad or angsty. Sooyoung came over with this song that became “Americruiser.” The whole package — the way the song preceded, the quiet and loud parts, the lyrics — it completely captured what I was feeling. In the back of my head, I was like, “How did he do that?” It’s like he reached into the back of my brain and pulled out the lyrics that I didn’t know I wanted to write.

I feel like there’s a less active rock scene than there was when you were here.

It was active, but it wasn’t like Bitch Magnet played and 500 people showed up. It wasn’t until our last semester where it felt like people got excited. Pay the Man became a big deal their senior year on campus. There’s a scene at a Pay the Man show in the book that I’m really fond of, in the lounge of Barrows [Hall]. There were probably a couple hundred kids there. It mattered a great deal to me and my friends, but it didn’t mean that everyone showed up when Pay the Man played. It was still much more aggressive than most people wanted to hear.

What kind of music were you listening to when you were at Oberlin? Were you listening to other bands that sounded like what you were making?

Bitch Magnet was friends with Bastro and Slint. There was a lag between what they were onto musically and what had been released. So, we knew that, between their first and second records, Bastro was going to make this giant leap, because we’d been hearing those songs for a while. We knew that they had friends in Louisville — this band called Slint that was going to put out this really weird record called Tweez. We were completely obsessed with Tweez. When Spiderland came out, I was like, “It’s all right, but it’s not as good as Tweez.” It’s a really strange record; it’s kind of humorous in a very dry way. It really sounded like nothing else.

Jesus Lizard were starting. I didn’t love Jesus Lizard, but I loved David Yow, and I loved David Sims — I thought he was an amazing bassist. [I also listened to] all the Touch and Go [Records] and Homestead [Records] stuff at the time. Sonic Youth was really undeniable. My freshman year, in January of ’86, I saw Hüsker Dü play this old theater in Cleveland and it was the most terrifying, exuberating experience of my life. It sounded like one giant car crash; you couldn’t tell one song from another. It was so exciting.

Was there a moment when you felt you had reached the indie-rock equivalent of “making it” with Bitch Magnet, Don Caballero or any other bands?

Bitch Magnet actually did well in Europe. On our last tour, we sold out a venue of around 1,200 people in London. In the bigger cities, there’d be several hundred people there. It felt like something. I also knew the band was breaking up at that point, so I couldn’t get too attached.

Don Caballero played to much bigger audiences than Bitch Magnet did. In Chicago and New York City, 500 people would come see us. That was ecstatic. When you leave the club after soundcheck to get dinner and the place is packed when you come back, that feels great. But there were so many bigger bands of various stripes.

40 people in Morgantown, WV, or Grand Rapids, MI, on a Tuesday night was enough, though. I’ve been in bands where nobody comes. Anyone being there is kind of great. That’s where the whole thing starts.

How did you end up working at Inc. magazine? How did that come about in your life? Was it related to your interest in zines, or was it a separate entity?

I always liked writing and thought I was kind of good at it, whether I actually was or not. When I got out of school, I wanted to focus on music. I needed to something to pay the bills. My brilliant idea was to get involved in journalism, which is not a really good way to pay the bills. But I liked the people I was around, the work that I was doing, the process of reporting and writing and the atmosphere of a newsroom. I stuck with it.