Trump Administration Threatens Oberlin Arts Funding

Graphic by Kiley Petersen, Managing editor

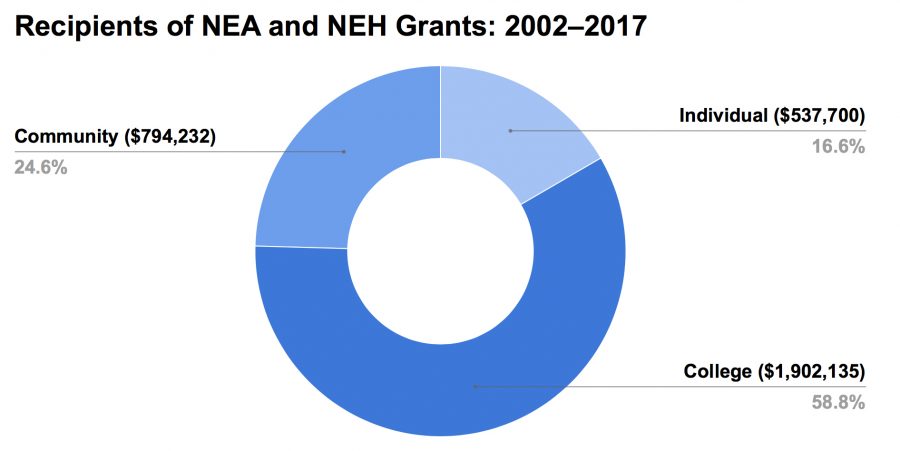

Since 2002, the College and Conservatory, faculty members and the Oberlin community have received more than $3 million in federal funds from the National Endowment for the Arts, the National Endowment for the Humanities and the Institute for Museum and Library Services, as well as funds from state affiliates, the Ohio Arts Council and Ohio Humanities Council.

March 10, 2017

Before President Trump took office in late January, multiple publications reported that his transition team had begun compiling a list of federal programs to eliminate in an effort to trim domestic spending. According to The New York Times, that list is expected to be finalized by the Office of Management and Budget next week as part of the President’s first federal budget proposal. According to ABC News, the forthcoming budget draws heavily on budget outlines produced by the Heritage Foundation, a conservative think tank, and the Republican Study Committee, a caucus of 172 Republican representatives in the House of Representatives that focuses on pushing conservative legislation.

The RSC’s plan, called the “Blueprint for a Balanced Budget 2.0,” proposes the elimination of a huge number of federal programs, including the National Endowment for the Arts, the National Endowment for the Humanities and the Institute for Museum and Library Services, each of which has provided funding to the College, Conservatory and Oberlin community in recent years. The NEH and NEA also fund state-level affiliates across the country, including the Ohio Arts Council and Ohio Humanities Council, both of which have also funded projects in Oberlin.

Despite accounting for a miniscule fraction of the federal budget — a combined .014 percent of the government’s $4 trillion in spending projected for this fiscal year — the funds are significant to Oberlin. Since 2002, the College and Conservatory, individual faculty members, the city of Oberlin and Oberlin community organizations have received more than $3 million in support from the NEA, NEH, OAC, OHC and IMLS. The money has impacted a variety of people and groups in Oberlin: Recent recipients include community organizations like Oberlin Choristers and the Firelands Association for the Visual Arts, Professors Lynn Powell and Ann Sherif and the Allen Memorial Art Museum.

For Andria Derstine, the Allen’s director, the national endowments have been crucial.

“It’s been huge. It’s been really important for us,” Derstine said. “One of the [grants] that we got most recently from the National Endowment for the Humanities was a $500,000 Challenge Grant that had to be matched three to one to endow our curatorship in Asian Art, and … we have done that. But if it had not been for that Challenge Grant, who’s to say if we would’ve gotten the matching money in another way? That really enabled … us to hire a full-time, endowed curator of Asian art, and Asian art is about a third of the collection at the Allen. To have someone in here full-time — in perpetuity, now that it’s endowed — is really important in terms of teaching with that collection and doing exhibitions with our collections, reaching into classes not only in East Asia[n] Studies, Art History and History, but all across the curriculum.”

According to Derstine, the Joan L. Danforth Curator of Asian Art position that the NEH’s funding helped create, now held by Kevin Greenwood, has been important in the museum’s programming around Asian art. Greenwood’s impact seems clear from the Allen’s current exhibitions alone: He curated four of the museum’s 11 currently on view — Conversations: Past and Present in Asia and America; Marking Time: The Seasonal Imagery in Japanese Prints; Lines of Descent: Masters and Students in the Utagawa School and The Archaic Character of Seal Script. Derstine noted that the grant’s impact has stretched beyond the exhibitions themselves.

“[There] has been a significant uptick in the number of exhibitions we’re able to do around Asian art, the number of classes we’re able to serve, the number faculty and students we’re able to serve and the amount of teaching, … scholarship and research that goes on here in that field,” she said.

Along with the multitudes of students reached by the Allen’s programming made possible with the help of federal funds, grants and stipends from the NEH, NEA and OAC have helped faculty members from the College and Conservatory advance their own work. Last summer, Assistant Professor of Music Theory Megan Long received a summer stipend of $6,000 from the NEH that facilitated research for her book.

“I work on popular music in the 16th century, and my question about it is: ‘How does that contribute to the big change that happened in music between the 16th century and the 18th century?’” Long said. “[The grant] funded two months of my time to research and write about this thing. I needed to go to Europe to look at some of these 16th-century books, because most of them, there’s only one … or two copies that survive, and they don’t [loan those out]. You have to fly to the library that houses them and get permission to look at them, and then spend some quality time with them to learn about them so you can write about them.”

Furthermore, grants have had significant reach in the Oberlin community. In 2015, the city received a $25,000 grant from the NEA to “strengthen the community economically, by developing and promoting Oberlin as an arts destination” and to “raise community and visitor awareness of downtown Oberlin and its contents and other historic sites and recreational opportunities.” Every year since 2012, the Oberlin Summer Theater Festival, which presents free, professional productions of classic theater works, has received a grant from the Ohio Arts Council. This year, the festival reached nearly 12,000 people, according to Pamela Snyder, the executive director for the Office of Foundation, Government and Corporate grants.

When faced with the prospect of elimination of federal programs supporting the arts, humanities and related areas, Derstine and Snyder are concerned about the prospect of another reduction to resources in an already highly competitive funding landscape. According to Snyder, the funding rates for summer stipends and fellowships from the NEH are around five or six percent, and the NEA has had few individual awards since the 1980s when its budget was last cut.

“Unfortunately, the opportunities for funding in the humanities are not terribly great for scholarship and so NEH has been such a bastion of support for humanities teaching and scholarship,” Snyder said, adding that in addition to the tenuous state of federal funding in the arts and humanities, the Great Recession could be clearly seen in fewer opportunities for funding from private organizations. Derstine agreed.

“Even though there is a universe of places you can apply to, including private sources, just to have any portion of that universe potentially go away is not a good thought, given how few options there really are in the arts and humanities,” Derstine said.

Despite the uncertainty that faces grant-seeking organizations like the Allen and individual professors seeking funding for their work, both Long and Derstine expressed that Oberlin is likely to fare better than many other educational institutions should President Trump’s budget plan come to fruition.

“We’re very lucky at Oberlin that the College also [has] funding available for faculty to travel, and that we’re funded to do our research in the summers,” Long said. “That’s not the case for everybody or every school, so I should preface that by saying that I could have done this research anyway, without the NEH grant, because Oberlin would have helped me pay for it. Having the funding from the NEH as well as Oberlin funding enabled me to do maybe a more ambitious trip than I would have been able to do otherwise. We’re very lucky here at Oberlin, but there are a lot of institutions where federal funding is one of the primary ways that scholars can go and travel and do their research. That will have a huge impact on the types of projects people are able to do, the types of questions people are able to ask and the kind of progress we’re able to make in our various fields.”

Snyder underscored this point further, noting that elimination of funds will mean that professors’ research opportunities will be much more dependent on their individual fortunes.

“I think for faculty, [elimination of federal funding] makes a difference in terms of the time that they can devote to projects [and] whether they can take the time off to do [them]. It certainly slows their research and … for some people it may be easier to take a leave than it is for other people depending on family circumstances or where they are in their careers, and having that [ funding] there keeps advancing scholarship and teaching, which is fundamental to what we as educational institutions do,” Snyder said.

For the Allen as well, the threat of losing the National Endowments is less existential.

“What I think about the most with this threat is the potential future special projects that we might not be able to do,” Derstine said.

Long, Derstine and Snyder all noted the value that the arts bring, something that seems to be misunderstood in Republican budget proposals, both in terms of geographical impact and overall return on investment.

“Both NEH and NEA … make sure that what they are funding … is touching every single congressional district, so these are programs that touch all Americans, and I feel like … we have to think about what a bargain it is. It’s a bargain that we’re getting as Americans with this very tiny portion of the budget that’s touching so many people and improving so many lives,” Derstine said.

You can read a full accounting of the federal and state funding received by the College and Conservatory, Oberlin faculty and the Oberlin community from 2002 – 2016 here.

Managing editor Kiley Petersen and Arts editor Victoria Garber contributed reporting.