Omid Shekari, Visiting Professor & Artist

Omid Shekari.

Omid Shekari is a visiting assistant professor in the Studio Art department. His exhibition, Of Aggression and Domination, focuses on the lacking media portrayal of United States military occupations abroad. His work looks into the militarization of the government, the violence committed against civilians, and the meaning of nationalism and patriotism. Shekari’s art has been exhibited around the world, and he has participated in residencies at MASS MoCA and OMI, among many others. He spoke with the Review about the inspiration for his work, the meaning of art, and biased portrayals in the media. Of Aggression and Domination opened in the Richard D. Baron ’64 Art Gallery on Nov. 7 and will be featured until Dec. 7.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

What message are you hoping to send with Of Aggression and Domination?

When I was offered to have a show here, I was thinking about who my viewers are, and a majority of my viewers are students — 18, 19, 20 years old. They read a lot about different issues, they are involved a lot in social issues, they’re very aware of a lot of things. And I wanted to let them know that there’s something that happened in the history of this country that the liberal and conservative media never covered because if the media covers it, they cannot sell it to people. Since it doesn’t bring benefits for them, they never cover such news. But I thought that if some people come here and see art about their history, maybe they can vote for someone that is anti-war, and they can think about outside the country, too.

What was your motivation for this exhibition?

I grew up in Iran, and the government was highly religious. I participated in various protests, and I was detained, and while I went through a lot of the process, I always thought, “What is death? How can we create a free world for ourselves?” And for whatever reason, that moved me to apply for grad school and to come to the U.S. I know about the problems, like racial problems … surrounding society in the U.S., [and I knew that I had] moved to the country [where there were] already more than 3 billion guns in the hands of people, and [there was a] culture of massacring millions of Indigenous Americans and animals. And the culture which has enslaved, raped, humiliated, lynched, and generally brutalized millions of other humans within these centuries. A culture of aggressively meddling, murdering, and dehumanizing tens of millions of people around the world. Yet I was the one who looked like a threat; that was, for me, what told me something was wrong in this society. … Because I have brown skin and I look like a person that the media targeted, and I’m a victim of Islamophobia. I was thinking that if I make art for American viewers, I have to make something to be able to communicate and increase some awareness about the history that they probably don’t want to read, [and] that is affecting me personally and millions of other people around the world.

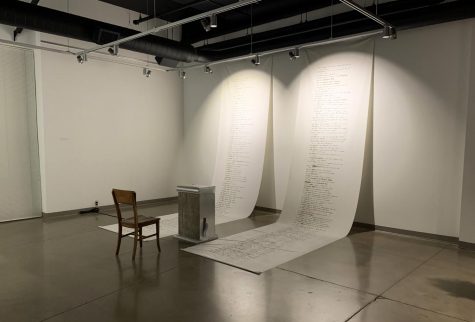

The last series of work that I had in Philadelphia, which led to this exhibition, began with researching a lot about the reasons why the United States creates this military culture, how everything is around this military, either being a part of this military, or a lot of benefits for the people who serve for the military. One thing that was very big for me was looking back in history and seeing all of these imperial societies. … We are very close to the rise of fascism [again]; it always comes out of militaries, imperialists, and very powerful countries. So the U.S. now has more than 800 military bases around the world everywhere, in each country you can imagine, except maybe three or four. And as you see in [the “For the Best”] list [featured in this exhibition], these are the military interventions since the Civil War in the United States, and they’ve been to so many places in South America, in Africa, in Southeast Asia, in Asia, in the Middle East, [the] Balkan[s] — everywhere you can imagine, they had their military presence. And I really wanted to communicate that with the viewers.

Can you tell me a little bit about the piece “For the Best”?

It’s called “For the Best” because I was thinking about all the ways they sell this military, how the politicians for their own interests find a way to sell it. They said for national security, they have to send some troops, and so they send troops that never come back; they just stay there because that’s the way to put pressure on the country and to push the policies that the United States wants to impose on another country. So, I call it “For the Best” because of the advertising of the best for the people in [American] society.

I noticed that a lot of your pieces are multimedia. What was your intention behind this artistic choice?

I was trained as a very academic painter, painting on canvas and drawing on paper. But as I looked at a lot of artists and I learned about art and art practice, I thought that drawing is a thought process. Anything is inside of you; you can just create and see what is inside your brain. It doesn’t matter if you create a line with graphite on paper or create a line with a piece of metal in a parking lot. That line is a line. So I try to teach students that you can make drawings within any kind of media. It could be on a paper, it could be on canvas, it could be a sculpture, it could be a video animation, etc.

Have your students seen the show?

Most of my students saw the show, and I tried to show them a lot of artists that I admire that work with the same ideology and the same manifestation, not necessarily about U.S. politics, but art as a means of increasing awareness, increasing activism. I think they kind of understand what I’m doing after seeing all those artists.

In what ways does Of Aggression and Domination touch on other themes that you haven’t explored in exhibitions before?

[This exhibition is different] in the case of the form I’m using here, probably like this piece, [called] “I can’t read it.” People can just sit and read the testimonies of the people who joined the Marines and the troops that joined the Vietnam War, the Iraq War, and the Afghanistan War. They came back, and they gathered together as a group called Winter Soldier. They spoke about their experiences [of things] that they’ve done to people or they witnessed other U.S. troops [do] to people. They’re very shocking. They cut off heads, they cut off limbs, they did horrible things that you can’t imagine. One person said something, and then they just kill[ed] a whole village because they had the power to do it, and there was no [consequence] for them.

For example, one of them is this one that I read [called] “My right leg is 4 inches shorter than the left one!” [in which] he talks about his first confirmed kill. And he says that [the] person was innocent, and because he hit him and this guy was protesting “Why are you screaming? Why are you hitting me?” He just killed him. And he was congratulated by his commander because he killed someone. This is the culture of militaries, that people in the United States — when I’m talking about people in the United States, I’m talking about people like the middle and higher class, mostly white people — don’t experience this level of violence. I’m not sure that a lot of people coming to this show like what I’m doing. But for me, art is not entertainment. For me, art is a way of communication and revealing the truth, and also [to] a great extent, a level of activism.