COVID-19, Climate Justice Fundamentally Linked

Tyler LaRiviere/Chicago Sun-Times

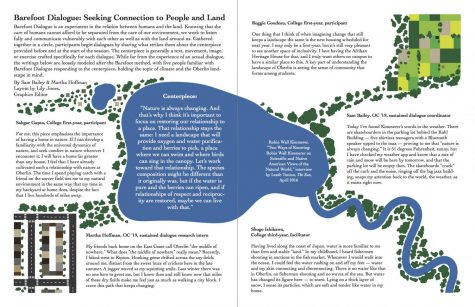

Earlier this month, the demolition of the Crawford coal plant’s smokestack sent dust billowing into the Chicago community of Little Village in the midst of a global pandemic.

When this Editorial Board first met to discuss possible directions for our work in this issue, the possibilities seemed limitless. After all, environmental themes like resource overuse, air and water pollution, and environmental policy and racism all intersect with the Oberlin community in countless ways as climate change continues to impact life around the world, including in Northeast Ohio.

Now, as we complete this magazine while sheltered in place, our futures have changed in ways we had not imagined. The COVID-19 pandemic has come to encompass all aspects of daily life, and its intersections with the climate crisis — and how we think about personal responsibility, equity, and public health — require our attention and focused effort.

An early tendency has emerged among American government officials orchestrating the public health response to refer to COVID-19 as “the great equalizer.” The inclination behind this sentiment is understandable; if you are a governor, for example, you want every single resident to exercise the utmost caution, regardless of their social and economic position.

However, the realities on the ground reflect a public health crisis that is anything but equal. COVID-19 is hitting hardest in communities that have endured environmental injustices for generations. From Louisiana’s Cancer Alley to Detroit’s most polluted zip codes, people in marginalized communities — particularly Black, Indigenous, and Latinx communities — are dying at much higher rates than the rest of the population.

Harvard university researchers have already identified an early positive correlation between the presence of air pollution and COVID-19 death rates. Decades of discriminatory housing practices and disproportionate siting of high-pollution facilities in marginalized communities are now concentrating adverse public health outcomes, particularly in communities of color.

The stories that have emerged from this violent convergence are heart-wrenching. Just this month, developers in Chicago demolished the smokestack of the old Crawford coal plant. The demolition sent clouds of dust billowing into the community of Little Village, a predominantly Latinx, lower-income neighborhood already beset by a range of environmental justice concerns. Among these concerns is a high asthma rate, which results from the longtime operation of this facility and its twin, the Fisk coal plant.

After the dust settled on Little Village, Hilco, the responsible developers, apologized, saying that they had not expected the demolition to produce such a high quantity of potentially harmful dust. While Hilco did take steps to offer cleanup services and distribute masks to residents, much of the damage was already done.

The apology is particularly inadequate because, while Hilco maintains that it did not know the demolition would go so poorly, the residents of Little Village — who fought for years to shut down the Crawford and Fisk coal plants — knew exactly what was going to happen. They knew because the geography of environmental injustice in this country has, for years, clearly drawn the lines around whose concerns and health are prioritized and whose are not.

When politicians call COVID-19 “the great equalizer,” they may be well-intentioned, but they also obscure the rifts of race and class that U.S. residents live with and within. We need to examine the role that the rhetoric of personal responsibility has played in how the pandemic is talked about in the United States, and the ways that it connects to how agency is framed in the context of the climate crisis and environmental issues more broadly.

There is widespread agreement that President Donald Trump’s administration has failed in its COVID-19 response. It ignored the warning signs and failed to ramp up testing capability in a timely manner. The unequal and devastating impact of COVID-19 on Black, Indigenous, Latinx, and immigrant communities is not just the result of a few capricious choices and an incapable leader, however. Environmental racism in what is now the U.S. has a 500-year history of genocide, colonization, enslavement, discrimination, mass incarceration, xenophobia, and militarism. Environmentalists have often failed to identify these structural injustices. Historically, this has resulted in xenophobic rhetoric and policies around population and immigration.

What the COVID-19 pandemic and climate disruption make clear is that we’re here because forces more powerful than any one of us as individuals have created an economic system so exploitative that it puts all of us at risk. That risk is unevenly distributed, falling disproportionately on communities of color, both globally and here in Northeast Ohio.

There is one notable difference between these dual existential threats: The pandemic shut down life around the world within a matter of weeks, whereas the onset of climate change has been a little more staggered, with wealthier communities being slower both to feel the impacts and react. But make no mistake — life has already been fundamentally disrupted in many communities as a result of climate change; to regard the pandemic as the present crisis and climate change as the future one would be a grave error.

In matters of both COVID-19 and climate, we must keep the larger players in view. Our fight is not with each other, but with the drivers of a globalized fossil fuel economy that have landed us where we are today. As Mary Annaïse Heglar, OC ’06, says on page 39, the narrative of climate change is not that complicated, and the villains are not that shrouded.

Still, beyond the general injustice of the entire situation, why comment on the public health implications of the COVID-19 pandemic — and a connected crisis in Chicago — in a publication geared primarily toward readers connected to Oberlin? After all, Ohio was among the states best prepared to handle its outbreak; we have already passed the peak in terms of daily necessary hospital resources, and have not come close to exhausting our statewide supply of hospital beds and other resources.

Because, while all of this is true, this is almost certainly not going to be the last pandemic of our lifetimes. Already, scholars and journalists — including Oberlin’s own Sonia Shah, OC ’90, whose interview is featured on page 51 — have identified shrinking wildlife habitat as at least part of the reason COVID-19 was introduced to human populations. Other anthropogenic landscape impacts will only spread diseases further — including the melting of the polar ice caps, which are expected to contain viruses that have been frozen beneath the Earth’s surface for thousands of years, never encountered by anything, or anyone, currently living.

While Ohio was fortunately well-prepared to weather this storm, we might not do as well the next time around. As discussed on page 24, Lake Erie’s southeast coast is among the regions with the highest concentration of toxin-producing facilities in the U.S. — each one of these sites contributes to negative public health outcomes, which would only be expounded upon if the next public health crisis hits the state harder than this one did.

As we look toward the future, we know this incredibly painful moment will pass — although not for everybody. Many families, schools, churches, and communities will not be whole on the other side. In remembering those lives lost, we return to the words of author Arundhati Roy: “Another world is not only possible, she is on her way. On a quiet day, I can hear her breathing.”

We must meet this moment, as we should meet all painful moments: by taking the time we need to grieve and recover, and then imagining not only how we can be better, but also how we can shape the systems we’ve built to do better in the future. If they can’t do better, we must work to cast those systems away and build better ones in their place.