Judas and the Black Messiah Deservedly Valorizes the Black Panther Party

Judas and the Black Messiah stars Daniel Kaluuya as Fred Hampton, the charismatic young chairman of the Illinois Black Panther Party chapter in the late 1960s.

America is at war with Black people, and no group is more aware of this ceaseless conflict than the Black Panther Party. The BPP stands for the end of capitalism and the liberation of Black people everywhere, especially in America’s inner cities, and by any means necessary. At the core of the movement advocating for Black revolution are the charismatic leaders, both current and past, who continued and will continue to spur their people on to the very end.

Released in theaters and on HBO Max Feb. 12, Judas and the Black Messiah closely follows the stories of two Black men whose legacies are forever tied to the BPP: Chairman Fred Hampton (Daniel Kaluuya), founder of the first Rainbow Coalition and leader of the 1960s Chicago chapter, and William O’Neal (LaKeith Stanfield), head of security and the undercover FBI mole who was instrumental in Hampton’s downfall. Co-starring Dominique Fishback as Deborah Johnson, speechwriter for the Chicago chapter and Hampton’s love interest, and Jesse Plemons as FBI Special Agent Roy Mitchell, who oversees O’Neal, this historical drama was directed and produced by Shaka King.

The movie revolves around O’Neal’s moral conflict as he plays for both sides in the midst of racial warfare. Initially, Mitchell intimidates O’Neal into becoming an FBI mole by claiming that the BPP is as much of a terrorist threat as the Ku Klux Klan. This kind of coercion reflects real sentiments at the time — and today. White-dominated power structures and media can influence Black people to doubt their own communities.

The Black Panthers were controversial even among Black people due to their audacious, radical defiance and willingness to use violence — all of which the film does not shy away from representing. At the same time, far more violence is enacted by the authorities upon the Panthers than in reverse.

For the most part, the film portrays the Panthers as a positive force that helped their community, while staunchly defending themselves from unwarranted attacks. King does an excellent job of showing how the BPP are powerful, revolutionary heroes. The two most influential Panthers, Hampton and Johnson, bring ceaseless strength and power to their portrayals of events bigger than themselves, embodying the movement. Deborah Johnson’s presence in the movie explores motherhood, art, and Black femininity within the Black Panther movement. This inclusion was refreshing — women’s heroism and bravery in revolutionary movements are often overshadowed by the contributions of their male counterparts. Fishback’s expressive eyes convey Johnson’s ceaseless strength as a mother of the revolution in a powerful yet tender and humanizing performance.

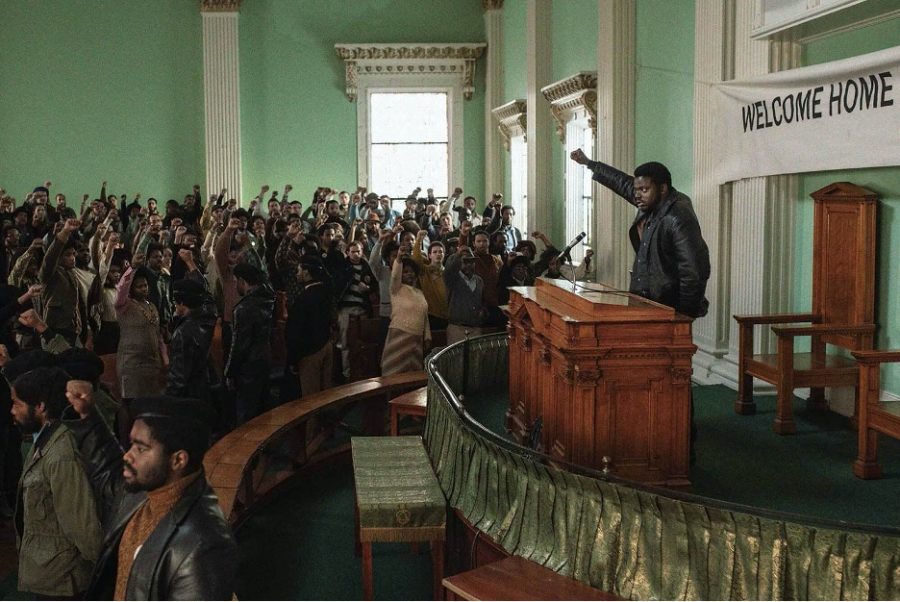

In addition to its frank presentation of racial politics in America, the film takes the unique position of subtextually adapting these very real events to a biblical narrative. The phrase ‘Black Messiah,’ coined in the narrative by the FBI, participates in partially deifying Fred Hampton. This framing creates a clear moral balance between leaders in the BPP, the FBI, and their informants. The biblical metaphor is woven into the film in multiple ways, most strikingly through the intensity of Hampton’s speeches. Kaluuya’s performance is electrifying, and the effect on the audience, both in the crowds in the film and as real viewers, is palpable. The monologues are interspersed with chants — credit to the sensational scene work during the “I am a revolutionary” speech — and a recurring declaration of the political and economic goals of the organization. Hampton isn’t just speaking; he is preaching. And based on the roaring responses of the crowds, it’s working.

In the film, Hampton isn’t just a messianic figure for the sake of the parable — it genuinely portrays him as that much of a hero. The writing juxtaposes his public personality with his private life: Here is a man whose life is defined by his belief in the mission, existing more confidently in the public light than in intimate spaces. He isn’t just a political revolutionary; he is the revolution. He embodies the struggle and personifies the beliefs of the Black Panthers; his followers are wholly dedicated to him and, through him, the revolution. His real name is used only a handful of times, everyone just calls him ‘Chairman.’ This iconic status is best articulated in the way Johnson frames the Chairman as both a tender lover and someone worth believing in.

The progression of the plot is also heavily influenced by this extended metaphor. In particular, there is a scene toward the end that could be held akin to the biblical Last Supper. The Black Panthers, including Hampton, Johnson, and O’Neal, are gathered around dreaming about ways to circumvent the government forces which seek to persecute Hampton. The camaraderie in the room is palpable, but the audience can tell that Stanfield’s character is ill at ease. Off-screen, O’Neal commits his final and most heinous betrayal against the Chairman and leaves, never to see Hampton again. This moment makes a definitive statement on who the protagonist is: Hampton’s dying moments are barely visualized as opposed to the number of scenes depicting O’Neal’s guilty agony.

It was, however, a curious decision to position Stanfield’s character O’Neal as the protagonist. While we bear witness to his internal conflict and legitimate belief in his moral righteousness, he is still the Judas figure within the narrative. As an audience, we view most of the film’s story around the structure of his life, we are privy to his ideologies, and for what it’s worth, the film begins and ends with him. Stanfield acutely portrays the anxieties and identity crisis of playing both sides in a violent conflict; every choice he makes can have multiple meanings. His quiet demeanor makes him a perfect spy, suddenly appearing amongst the Black Panthers ranks undetected. Stanfield brings O’Neal’s internal conflict to the surface in a masterful way. Merits of Stanfield’s performance notwithstanding, O’Neal is an undeniably problematic, if only a somewhat untrustworthy conduit to the audience. Yet, to have him be the protagonist makes the crucial narrative decision of constructing a distance between the audience and his foil, Hampton, which further accentuates Hampton’s larger-than-life presence.

Despite the tragic events of the film, Hampton’s legacy lives on in our world today. He is credited with creating the first multicultural Rainbow Coalition, a radical socialist organization that spurred many others across the country. Deborah Johnson, now known by Mother Akua Njeri, is still active in the party to this day, and her input helped to make this movie the sensation it came to be. Watching this movie is a gripping way to get in touch with nuanced aspects of history that were obscured by the prevailing white lens, and we highly recommend watching it this weekend.