Review: Flora, the Red Menace Provides Non-Lobster Perspective on Communism

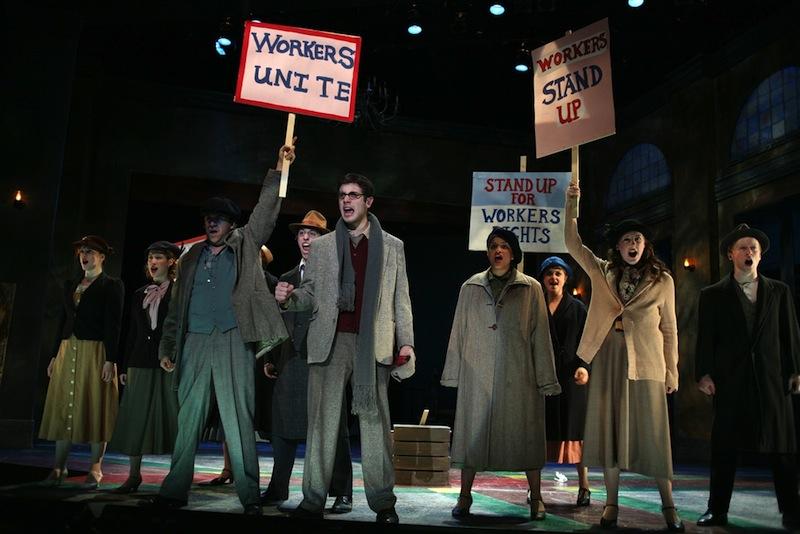

As communist love interest Harry, College junior Andrew Gombas sticks it to the man alongside hordes of protesters.

May 13, 2011

Before musical theater kids belting the tunes fromFlora, the Red Menace debunked my preconceived notions of the show’s plot, I was excited to see the nascent work of John Kander, OC ’51, a musical theater legend who wrote his first show about a lobster florist ostracized by his/her circle of lobster friends for his or her “menacing” behavior. Unfortunately, after I sawFlora, my desire to see shimmying crustacean florists was left wildly unfulfilled. In fact, it seems like songwriters Kander and Ebb neglected many theatergoers’ needs, including the need for a reasonably timed bathroom/Snickers break. Indeed, audience members leaving this solid production — which featured ambitious direction, a beautiful set, fantastic acting and commendable Snickers — of a rather nauseating and nearly three-hour-long show may have found themselves wondering: “If Flora wasn’t about an ill-tempered lobster florist, what, then, was it about?”

Given the show’s title and the lyrical content of some of the songs, the initial and perhaps most obvious answer to this question is that Flora is a lightly scathing commentary on communism, of its abduction and destruction of the individual. In many ways, it condemns communism for hypocritically claiming to be the solution to the manipulative capitalist machine, while at the same time acting as a manipulative and constricting machine in itself (as embodied by Conservatory senior Cree Carrico’s show-stopping performance as the duplicitous Comrade Charlotte).

However, in order for this political commentary to make sense, communism would have to be represented by more than amusingly simple songs decrying, as College junior Andrew Gombas does in his attempt to convert the titular character to communism, “Are you in favor of the rights of Man? / If you’re in favor of the rights of Man / here sign, sign here. / How about milk and cookies for the kids? / You gotta have milk and cookies for the kids / Here sign / Sign here.” This insipid argument is apparently enough to sway College senior Holland Hamilton’s Flora, who (ostensibly being something of a cookie monster) sells her soul to the Communist Party.

It seems, however, that Flora’s value as political commentary lies mostly in absurdly essentialized numbers such as these, and thus cannot serve as the principal driving forces of the play. After two or so hours, one is therefore led to believe that the show isn’t about the struggle to maintain individuality while stuck inside the communist machine, but rather about the struggle to maintain individuality within any society, as Flora’s individuality is questioned by the Communist Party, by her romantic ties and by the workaholics at the department store that has just hired her.

After hours of narrative tangents and general structural weirdness, Kander and Ebb give us this much: Flora is about the struggle for identity in times of widespread destitution. It is about the struggle for identity and individuality within systems desperate to quash these entities. It is about silly accents. It is about meta-theater. It is about the struggles of women like Carrico’s Charlotte to remain in their corsets, and the struggles of women like Flora to remain violently attracted to men with speech impediments. It is a little of all of the above. However, one thing is for certain: The common-but-ever-pertinent principal theme of individuality was so overwhelmed by digressions from the plot — in the form of the uninspiring love story, for instance, as well as the myriad of dance numbers allotted to the play’s minor characters — that the eventual downfall of the individual ends up packing more of a limp swat than a punch. Thanks to the impressive aesthetics and performances of this production, however, this limp-swatting hand happened to be wearing gems.