City Meets Target, Halves Carbon Emissions

February 20, 2015

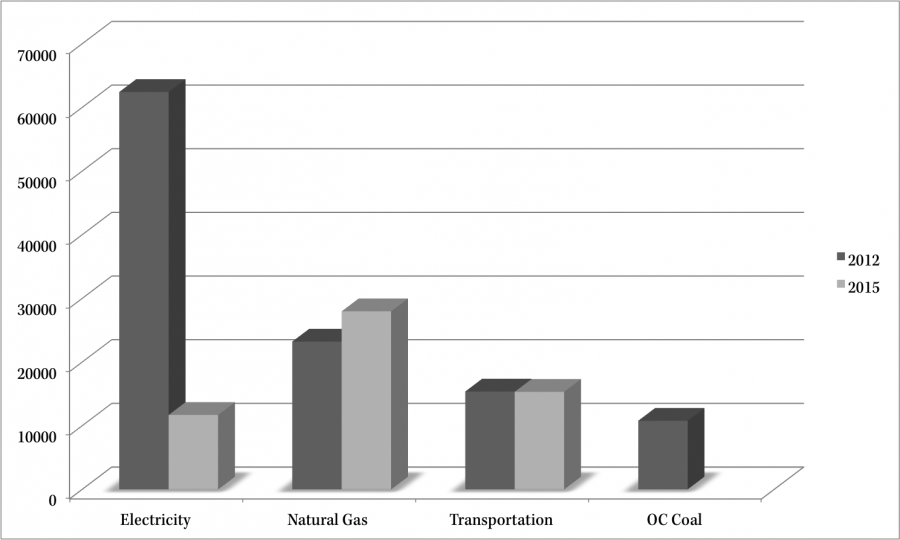

The city of Oberlin has met its target of cutting 2012 greenhouse gas emissions in half by 2015. Oberlin emitted 113,832 metric tons of greenhouse gases in 2012 and is projected to emit 56,866 metric tons in 2015, according to analysis done by the consulting firm Cameron-Cole.

“In three years, we halved the entire city’s greenhouse gas emissions,” said Sean Hayes, the executive director of the Oberlin Project. The Oberlin Project is an organization that seeks to help Oberlin make progress on a wide variety of environmental issues and coordinates action between the city, College and other local organizations. “It’s really remarkable. When you actually deal with this stuff on a day-to-day level and know what’s involved, you say, ‘Really?’”

Hayes attributed the decrease mostly to changes in the city’s energy portfolio, as electricity generation in 2015 is projected to emit only 19 percent of the amount of greenhouse gases emitted by power plants serving Oberlin in 2012.

Instead of relying primarily on coal, as the city did in 2012, Oberlin now gets the bulk of its energy from landfill gas — methane that is emitted from landfills, trapped and burned for energy. The city’s electric portfolio is now 24 percent hydro power, 3 percent solar energy, 3 percent wind energy and 55 percent landfill gas. The last 15 percent consists of coal, nuclear power and natural gas. Oberlin now gets roughly 85 percent of its energy from renewable sources — if one considers landfill gas to be renewable energy.

Some environmental groups, such as the Sierra Club, oppose the classification of landfill gas as renewable energy on the grounds that the process depends on pollution and that burning methane produces greenhouse gas emissions. In contrast, the federal Environmental Protection Agency and the Ohio EPA both classify landfill gas as a form of renewable energy.

“In the long run, we shouldn’t have landfills, and then we won’t have landfill gas,” Hayes said. “But in the meantime, there’s a huge amount of methane that comes off of landfills. Methane is essentially the main component in natural gas, so it can be burned and used in the same way natural gas can. And to top all of that, if you don’t use it, the way that landfills used to vent that methane was just into the atmosphere, and methane is 20 to 21 times more potent a greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide. So it’s a win-win-win while we have landfills.”

According to Doug McMillan, energy services and sustainability initiatives manager at Oberlin Municipal Light and Power System, landfill gas works well for a town of Oberlin’s size.

“In the whole United States, renewable energy is only 11 percent or 12 percent of the whole picture. Because we’re so small, we’re able to buy enough to get to 85 to 89 percent [renewable energy]. For Cleveland, there probably wouldn’t be enough [landfill gas] in Ohio to supply them with that size,” McMillan said.

McMillan added that he did not foresee the city going 100 percent renewable energy anytime soon because the city purchases the remaining 15 percent of nonrenewable energy from other electric companies. According to McMillan, renewable energy is expensive to create and thus hard to sell at a competitive price, so the city does not want to create more renewable energy than for which there is local demand.

The city has 15-year contracts with landfills in Mahoning County and Geneva. Even when the contracts expire in 2026, however, Oberlin still has right of first refusal and could choose to unilaterally renew its contracts with the waste management companies.

To David Orr, special assistant to the president on sustainability and the environment, the crucial moment came in 2008 when the City Council had to decide whether or not to continue using coal after the old coal-fired power plant that Oberlin relied upon for its energy was set to go offline.

“The default setting in January of 2008 was that we were going to buy into a thousand-megawatt coal-fired power plant for 50 years down in Meigs County. We won the vote not to do that in a 4–3 vote. That helped us dodge the bullet,”Orrsaid.

Orr credited David Sonner and David Ashenhurst as the Council members most responsible for Oberlin’s shift away from coal.

“If they had not led that battle and won the fight in ’07, ’08, ’09, we would be a coal-fired powered city for a long time to come. It was unpopular, but they did the right thing,” Orr said.

Another important factor in the large decrease in the city’s carbon emissions was the switch from coal to natural gas in the College’s steam plant in 2014. According to the Cameron-Cole statistics, the College’s coal usage constituted almost 10 percent of the entire city’s carbon emissions in 2012.

However, the College’s use of natural gas is emblematic of what Hayes described as the “next challenge” in the quest to further reduce emissions: finding ways to reduce or replace the use of natural gas as a means to heat homes and businesses. Natural gas is projected by Cameron-Cole to constitute nearly half of the city’s carbon emissions in the coming year, and the low cost of gas makes it a very alluring energy source for many residents.

“Gas has the lowest carbon emissions of any fossil fuel when it’s burned, so there’s a lot of people switching to gas right now,” Hayes said. “Partly it’s the fact that gas actually has really low transmission costs to move it from place to place, and it has really high storage capacities within the pipeline system of the U.S. Given the proliferation of fracking, the price of gas is really cheap.”

According to Hayes, getting residents to stop using gas also poses equity concerns. “It’s a really tough challenge, because if you want to go carbon neutral on the city scale in a replicable way that doesn’t gentrify a community and doesn’t price lower income residents out of their homes, you can’t just say, ‘We’re going to move everyone off gas right now,’” Hayes said.

Hayes added that he was hopeful that technologies like electric heaters and biogas could, in time, replace natural gas as the method of choice for Oberlin residents trying to heat their homes and businesses. Hayes also touted the savings generated by Providing Oberlin with Energy Responsibly, a local nonprofit group that, among other things, weatherizes low-income residents’ houses for free.

The next emissions reduction target that the city will try to reach to meet is 75 percent of 2012 levels by 2030. By 2050, the city aspires to be entirely carbon-neutral. Oberlin College has pledged to be carbon-neutral by 2025.

In December 2014, the White House recognized the city of Oberlin as one of 16 local governments deemed “Climate Action Champions.” Oberlin is also currently a semifinalist in the Georgetown University Energy Prize, an ongoing competition that focuses on reducing residential energy consumption and gives a $5 million prize to the winning community.